Why The Righteous Mind may be the best common reading for incoming college students

Given the political turmoil on many college campuses, and in America more broadly, what should incoming college students read before they arrive next September?

My publishers at Random House asked me to write up something they could hand out at the annual convention of people who pick common reading books for universities, and who plan out “first year experiences” to give all incoming freshman a shared set of ideas and experiences. I think the case for The Righteous Mind is pretty clearly stated in its subtitle: Why good people are divided by politics and religion. Below is the text that Random House has posted to accompany the book. It may be of use to any professor picking readings for next fall for any course with political content.

Americans have long known that they have racial, ethnic, class, and partisan divides. But the 2016 presidential election has forced all of us to recognize that these gaps may be far larger, more numerous, and more dangerous than we thought. Americans are not just failing to meet each other and know each other. Increasingly, we hate each other—particularly across the partisan divide.

Hatred and mistrust damage democracy, and they can seep onto campus and distort academic life as well. In these politically passionate times, and with all students immersed in social media, it’s no wonder that students, as well as faculty, often say that they are walking on eggshells—fearful of offending anyone by offering a provocative argument or by choosing the wrong word.

If you could pick one book that all incoming college students should read together— one book that would explain what is happening and promote discussion about how to bridge these divisions, what would it be?

My suggestion—The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion.

Here’s why:

1) The Righteous Mind is non-partisan, and teaches cross-partisan respect. I’m a social psychologist who has studied moral and political psychology for thirty years. I first began research for The Righteous Mind in 2004, motivated in part by a desire to help progressives do a better job of connecting with American moral values. But after immersing myself in the writings of all sides and doing my best to find the good on all sides, I became a non-partisan centrist. As I show clearly in my book, the three major philosophical camps—left, right, and libertarian—are each the guardians of deep truths about how to have a humane and flourishing society. I treat all sides fairly and respectfully and help students to step out of their “moral matrix” in order to appreciate the ways that ideological teams distort thinking, and blind us to the motives and insights of others.

2) The Righteous Mind makes big ideas accessible to eighteen-year-olds. The Righteous Mind takes students on a tour of the history of life, from bacteria through the present day, explaining the origins of cooperation and human “ultrasociality.” I explain what morality is, how it evolves—both biologically and culturally—and why it differs across societies and centuries. The book explores the fundamentals of social and cognitive psychology to explain why people are so susceptible to “fake news,” or anything else that offers to confirm our pre-existing judgments. In short, it is a book about some of the biggest and most pressing questions addressed by scholars today. This is why the New York Times Book Review hailed it as “A landmark contribution to humanity’s understanding of itself.”

The Righteous Mind has been widely praised by reviewers on the left and the right, many of whom noted that the book conveys the grandest ideas in language that makes it fun and easy to read.

From the left, The Guardian (UK) said: “What makes the book so compelling is the fluid combination of erudition and entertainment.”

From the right, The American Conservative said: “The author is that rare academic who presents complex ideas in a comprehensible manner.”

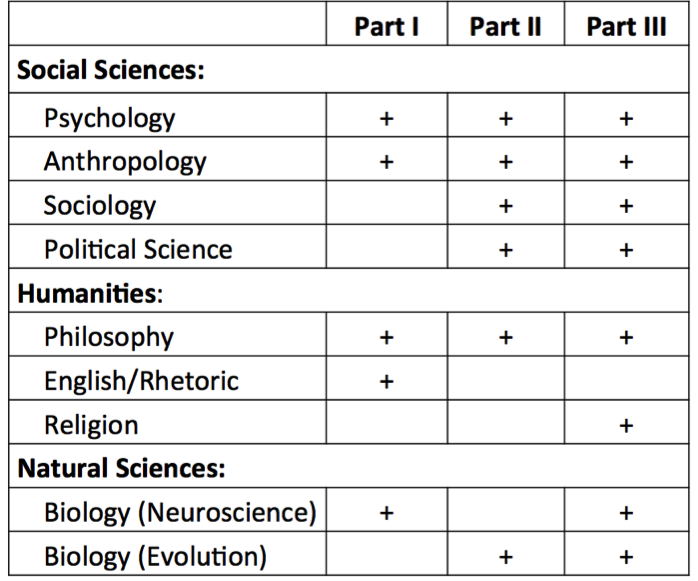

3) The Righteous Mind links together most of the academy. Like sexuality, morality is too multifaceted to fit within a single department, and I have drawn on scholarship from across the social sciences, humanities, and natural sciences. The Righteous Mind is one of the most interdisciplinary, trade books in recent decades, making it ideal as a common reading that professors across the university will be able to draw on. Students will be thrilled to find so many links among their classes—they’ll see that knowledge is often unified, and that the insights from each field often complement those of others. This table shows which disciplines are drawn on to a substantial degree in each of the three parts of the book:

4) The Righteous Mind comes with lots of supporting materials. I maintain and update regularly a website for the book: RighteousMind.com. The site has a tab of materials labeled “Applying Moral Psych.” There you’ll find a page of resources specifically for professors who are using the book in class. The page has links to videos to show with each chapter, links to projects, and videos created by students. It also has links to research sites, such as YourMorals.org, where students can obtain their own scores on the “Moral Foundations Questionnaire.”

5) The Righteous Mind will make all other conflicts on campus more tractable. In a time of rising conflict and tension on many campuses, The Righteous Mind will calm things down and teach students skills they can use to engage in difficult conversations. As I wrote in the introduction:

Etiquette books tell us not to discuss [politics and religion] in polite company, but I say go ahead. Politics and religion are both expressions of our underlying moral psychology, and an understanding of that psychology can help to bring people together. My goal in this book is to drain some of the heat, anger, and divisiveness out of these topics and replace them with a mixture of awe, wonder, and curiosity.

There is no better way to prepare for discussions of race, gender, climate change, politics, or any other potentially controversial topic than to start your students’ college experience by assigning The Righteous Mind as the “common reading” to your incoming class.

p.s., Short of asking students to buy the book, you could send them to my “politics and polarization” page, where there are many essays and videos. Also, Random House created a very short and inexpensive “Kindle Single,” which is basically just the last chapter, here.

Read MoreHow not to improve the moral ecology of campus

Writing at the philosophy/politics blog Crooked Timber, philosopher John Holbo offers a critique of my arguments about the need for more viewpoint diversity on campus. Holbo believes that my arguments contain an internal logical contradiction, which he explains like this:

Haidt is highly bothered about two problems he sees with liberalism on campus – and in other environments in which lefties predominate….

1) An unbalanced moral ecology. Allegedly liberals have a thinner base of values, whereas conservatives have a broader one. Everyone, liberal and conservative alike, is ok with care/no harm/liberty – although liberals are stronger on these. Conservatives are much stronger on the loyalty/authority/purity axis, since allegedly liberals are weak-to-negligible here…. So: not enough conservatives in liberal environments to ensure a flexible, broad base of values. How illiberal!

2) Political correctness. Haidt has a real bug in his ear about this one.

The logic problem is this. If 2) is a problem, 1) is necessarily solved. And if solving 2) is important, then the proposed solution to 1) is wrong (or at least no reason has been given to suppose it is right).

Holbo’s claim is that if PC is really a problem, then that necessarily means that universities are full of people who are…

“shooting through the roof along the loyalty/authority/purity axis. Because that’s what PC is. An authoritarian insistence on ‘safe spaces’ and language policing, trigger warnings and other stuff.”

But if campuses are truly full of left-wing authoritarians (he says), then there’s no imbalance in the moral ecology, because all of the moral foundations are represented.

But there’s a big problem with Holbo’s argument. I don’t say that the problem on campus is that there’s an absence of one or more foundations. I say, over and over again, that the decline in political diversity has led to a loss of institutionalized disconfirmation. This was our argument in the BBS essay on political diversity that got me started down this road, and which documented the rapid political purification of psychology since the 1990s.

And we say it succinctly on the Welcome page of Heterodox Academy:

Welcome to our site. We are professors who want to improve our academic disciplines. Many of us have written about a particular problem: the loss or lack of “viewpoint diversity.” It’s what happens when the great majority of people in a field think the same way on important issues that are not really settled matters of fact. We don’t want viewpoint diversity on whether the Earth is round versus flat. But do we want everyone to share the same presuppositions when it comes to the study of race, class, gender, inequality, evolution, or history? Can research that emerges from an ideologically uniform and orthodox academy be as good, useful, and reliable as research that emerges from a more heterodox academy?

Science is among humankind’s most successful institutions not because scientists are so rational and open minded but because scholarly institutions work to counteract the errors and flaws of what are, after all, normal cognitively challenged human beings. We academics are generally biased toward confirming our own theories and validating our favored beliefs. But as long as we can all count on the peer review process and a vigorous post-publication peer debate process, we can rest assured that most obvious errors and biases will get called out. Researchers who have different values, political identities, and intellectual presuppositions and who disagree with published findings will run other studies, obtain opposing results, and the field will gradually sort out the truth.

Unless there is nobody out there who thinks differently. Or unless the few such people shrink from speaking up because they expect anger in response, even ostracism. That is what sometimes happens when orthodox beliefs and “sacred” values are challenged.

Our concern at Heterodox Academy is very simple. It was expressed perfectly in 1859 by John Stuart Mill, in On Liberty:

He who knows only his own side of the case knows little of that. His reasons may be good, and no one may have been able to refute them. But if he is equally unable to refute the reasons on the opposite side, if he does not so much as know what they are, he has no ground for preferring either opinion… Nor is it enough that he should hear the opinions of adversaries from his own teachers, presented as they state them, and accompanied by what they offer as refutations. He must be able to hear them from persons who actually believe them…he must know them in their most plausible and persuasive form.

Holbo seems to think that if you were to start with a campus faculty entirely composed of non-authoritarian progressives (people like Nick Kristof or Barack Obama, who praise the importance of dissent), and then you added in some authoritarian progressives, who punish dissent on their most sacred issues, you would improve the campus ecology. Well, Holbo is right that you’d be adding a kind of diversity, but it’s one that is often hostile to other viewpoints. Mill and I and the rest of Heterodox Academy think it would be better to expose students—and professors—to people who hold views across the political spectrum, especially if you can do it within an institution that fosters a sense of community and norms of civility. We don’t care about balance. We don’t need every view to be represented. We just want to break up orthodoxy. Is that illogical?

Read More

Trigger Warnings Cause Non Sequiturs

Below is the letter to the editor that Greg Lukianoff and I submitted to the New York Times in response to an op-ed by Cornell philosophy professor Kate Manne, which defended the use of trigger warnings.

The Times did not respond to our submission, so here it is:

To the Editor:

Re: “Why I use trigger warnings” (Opinion, Sept. 19): Kate Manne’s efforts to alert her philosophy students about potentially upsetting course content shows her to be a caring teacher. But her critique of our essay condemning trigger warnings begins with a non sequitur. She is surely right that “the evidence suggests” that some of her students “are likely to have suffered some sort of trauma.” But that does not logically imply that “the benefits of trigger warnings can be significant.” We have not found any empirical evidence that trigger warnings yield any psychological benefits, whereas there is empirical evidence suggesting that they might be harmful. So it is more logical to conclude that if trauma is common, then the harms caused by trigger warnings might be significant.

Manne then offers an analogy: “Exposing students to triggering material without warning seems more akin to occasionally throwing a spider at an arachnophobe.” This is not a valid analogy. Asking students to read novels or Greek myths that include sexual assault is like saying the word spider in the presence of an arachnophobe, which anxiety experts tell us is a good way to reduce the long-term emotional power of spiders. If well-meaning teachers and friends work together to help an arachnophobe avoid exposure to the word spider, or to pictures of spiders, spider webs, and Spiderman, they will strengthen the arachnophobe’s conviction that mere reminders of spiders are dangerous. This is how a temporary and reversible phobia can be hardened into a lifelong and debilitating identity.

Manne also asserts that “there seems to be very little reason not to give these warnings.” It’s simple courtesy, no? Trigger warnings are like “advisory notices given before films and TV shows.” But those warnings are given so that parents can keep their children safe from material for which they are not yet emotionally mature enough. This is why the American Association of University Professors has condemned the use of trigger warnings as being “at once infantilizing and anti-intellectual.”

Furthermore, once a few professors start giving these warnings, students will begin to request them from their other professors, and this may lead to a cascade of caution among the rest of the faculty. Last year, seven humanities professors from seven colleges penned an Inside Higher Ed article stating that “this movement is already having a chilling effect on [their] teaching and pedagogy.” The professors reported receiving “phone calls from deans and other administrators investigating student complaints that they have included ‘triggering’ material in their courses, with or without warnings.”

There is a more subtle harm caused to students when professors use trigger warnings. One of us (Haidt) teaches in New York City. Suppose Haidt took his students on field trips all over the city, but every time he took the class to the Bronx, Haidt took additional steps: he gave the class a warning, weeks in advance, and he hired a paramedic to ride with them in the bus. Just in case. What effect will this have on the students, and on their future willingness to visit The Bronx on their own?

Do we really want to tell our students that some of their fellow students could end up in emergency care if they were to read certain novels without being properly steeled for the task? This message would reflect and strengthen the “culture of victimhood” that sociologists have identified as emerging on our most egalitarian college campuses. It could weaken students to the point where we might, someday, really need paramedics in our classrooms.

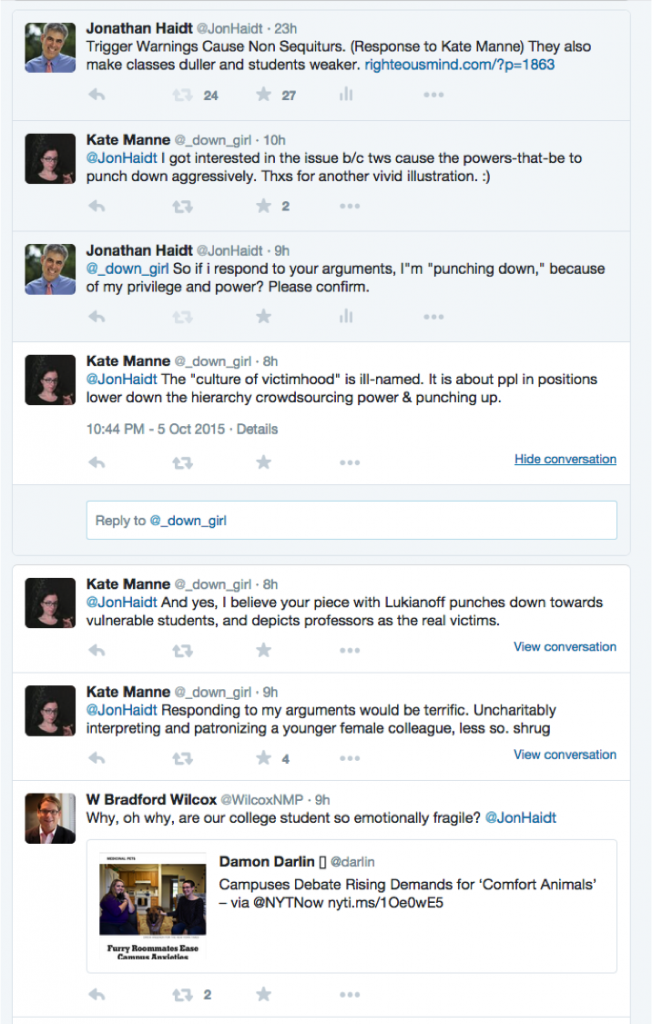

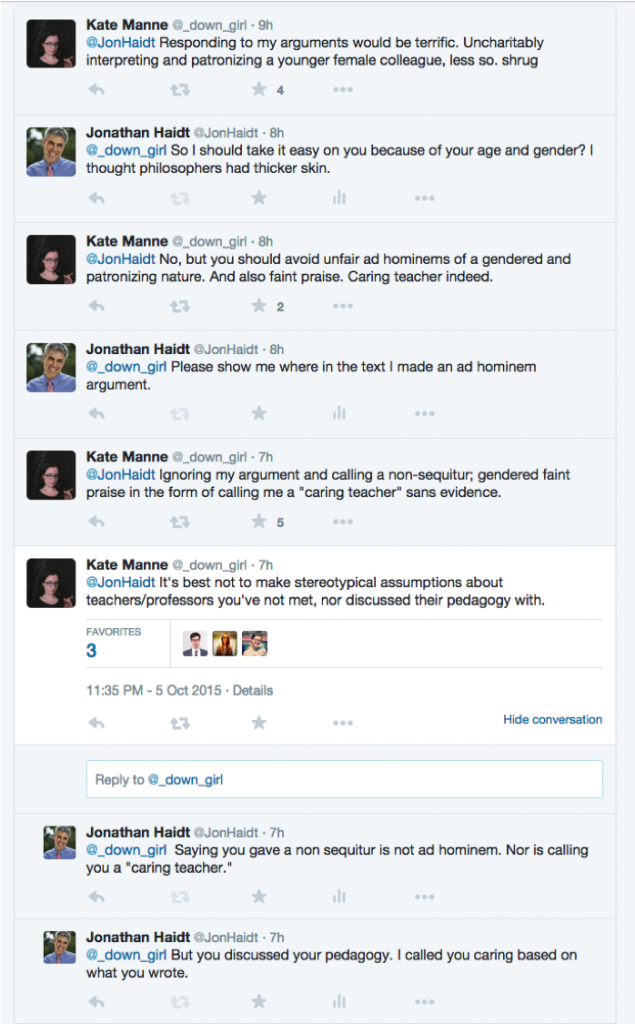

For the record, below is the Twitter exchange I had with Manne as a result of this blog post. Note that Brad Wilcox’s tweet was not part of this exchange — it just happened to be posted during my exchange with Manne.

Read More