Why The Righteous Mind may be the best common reading for incoming college students

Given the political turmoil on many college campuses, and in America more broadly, what should incoming college students read before they arrive next September?

My publishers at Random House asked me to write up something they could hand out at the annual convention of people who pick common reading books for universities, and who plan out “first year experiences” to give all incoming freshman a shared set of ideas and experiences. I think the case for The Righteous Mind is pretty clearly stated in its subtitle: Why good people are divided by politics and religion. Below is the text that Random House has posted to accompany the book. It may be of use to any professor picking readings for next fall for any course with political content.

Americans have long known that they have racial, ethnic, class, and partisan divides. But the 2016 presidential election has forced all of us to recognize that these gaps may be far larger, more numerous, and more dangerous than we thought. Americans are not just failing to meet each other and know each other. Increasingly, we hate each other—particularly across the partisan divide.

Hatred and mistrust damage democracy, and they can seep onto campus and distort academic life as well. In these politically passionate times, and with all students immersed in social media, it’s no wonder that students, as well as faculty, often say that they are walking on eggshells—fearful of offending anyone by offering a provocative argument or by choosing the wrong word.

If you could pick one book that all incoming college students should read together— one book that would explain what is happening and promote discussion about how to bridge these divisions, what would it be?

My suggestion—The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion.

Here’s why:

1) The Righteous Mind is non-partisan, and teaches cross-partisan respect. I’m a social psychologist who has studied moral and political psychology for thirty years. I first began research for The Righteous Mind in 2004, motivated in part by a desire to help progressives do a better job of connecting with American moral values. But after immersing myself in the writings of all sides and doing my best to find the good on all sides, I became a non-partisan centrist. As I show clearly in my book, the three major philosophical camps—left, right, and libertarian—are each the guardians of deep truths about how to have a humane and flourishing society. I treat all sides fairly and respectfully and help students to step out of their “moral matrix” in order to appreciate the ways that ideological teams distort thinking, and blind us to the motives and insights of others.

2) The Righteous Mind makes big ideas accessible to eighteen-year-olds. The Righteous Mind takes students on a tour of the history of life, from bacteria through the present day, explaining the origins of cooperation and human “ultrasociality.” I explain what morality is, how it evolves—both biologically and culturally—and why it differs across societies and centuries. The book explores the fundamentals of social and cognitive psychology to explain why people are so susceptible to “fake news,” or anything else that offers to confirm our pre-existing judgments. In short, it is a book about some of the biggest and most pressing questions addressed by scholars today. This is why the New York Times Book Review hailed it as “A landmark contribution to humanity’s understanding of itself.”

The Righteous Mind has been widely praised by reviewers on the left and the right, many of whom noted that the book conveys the grandest ideas in language that makes it fun and easy to read.

From the left, The Guardian (UK) said: “What makes the book so compelling is the fluid combination of erudition and entertainment.”

From the right, The American Conservative said: “The author is that rare academic who presents complex ideas in a comprehensible manner.”

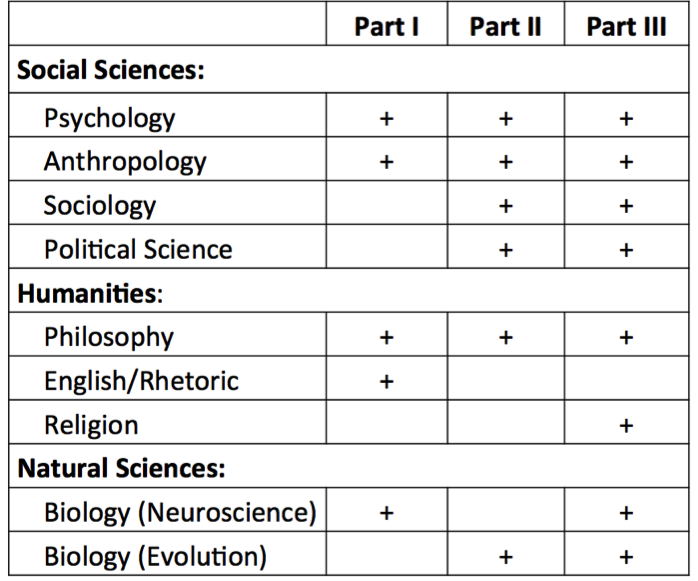

3) The Righteous Mind links together most of the academy. Like sexuality, morality is too multifaceted to fit within a single department, and I have drawn on scholarship from across the social sciences, humanities, and natural sciences. The Righteous Mind is one of the most interdisciplinary, trade books in recent decades, making it ideal as a common reading that professors across the university will be able to draw on. Students will be thrilled to find so many links among their classes—they’ll see that knowledge is often unified, and that the insights from each field often complement those of others. This table shows which disciplines are drawn on to a substantial degree in each of the three parts of the book:

4) The Righteous Mind comes with lots of supporting materials. I maintain and update regularly a website for the book: RighteousMind.com. The site has a tab of materials labeled “Applying Moral Psych.” There you’ll find a page of resources specifically for professors who are using the book in class. The page has links to videos to show with each chapter, links to projects, and videos created by students. It also has links to research sites, such as YourMorals.org, where students can obtain their own scores on the “Moral Foundations Questionnaire.”

5) The Righteous Mind will make all other conflicts on campus more tractable. In a time of rising conflict and tension on many campuses, The Righteous Mind will calm things down and teach students skills they can use to engage in difficult conversations. As I wrote in the introduction:

Etiquette books tell us not to discuss [politics and religion] in polite company, but I say go ahead. Politics and religion are both expressions of our underlying moral psychology, and an understanding of that psychology can help to bring people together. My goal in this book is to drain some of the heat, anger, and divisiveness out of these topics and replace them with a mixture of awe, wonder, and curiosity.

There is no better way to prepare for discussions of race, gender, climate change, politics, or any other potentially controversial topic than to start your students’ college experience by assigning The Righteous Mind as the “common reading” to your incoming class.

p.s., Short of asking students to buy the book, you could send them to my “politics and polarization” page, where there are many essays and videos. Also, Random House created a very short and inexpensive “Kindle Single,” which is basically just the last chapter, here.

Read MoreHow not to improve the moral ecology of campus

Writing at the philosophy/politics blog Crooked Timber, philosopher John Holbo offers a critique of my arguments about the need for more viewpoint diversity on campus. Holbo believes that my arguments contain an internal logical contradiction, which he explains like this:

Haidt is highly bothered about two problems he sees with liberalism on campus – and in other environments in which lefties predominate….

1) An unbalanced moral ecology. Allegedly liberals have a thinner base of values, whereas conservatives have a broader one. Everyone, liberal and conservative alike, is ok with care/no harm/liberty – although liberals are stronger on these. Conservatives are much stronger on the loyalty/authority/purity axis, since allegedly liberals are weak-to-negligible here…. So: not enough conservatives in liberal environments to ensure a flexible, broad base of values. How illiberal!

2) Political correctness. Haidt has a real bug in his ear about this one.

The logic problem is this. If 2) is a problem, 1) is necessarily solved. And if solving 2) is important, then the proposed solution to 1) is wrong (or at least no reason has been given to suppose it is right).

Holbo’s claim is that if PC is really a problem, then that necessarily means that universities are full of people who are…

“shooting through the roof along the loyalty/authority/purity axis. Because that’s what PC is. An authoritarian insistence on ‘safe spaces’ and language policing, trigger warnings and other stuff.”

But if campuses are truly full of left-wing authoritarians (he says), then there’s no imbalance in the moral ecology, because all of the moral foundations are represented.

But there’s a big problem with Holbo’s argument. I don’t say that the problem on campus is that there’s an absence of one or more foundations. I say, over and over again, that the decline in political diversity has led to a loss of institutionalized disconfirmation. This was our argument in the BBS essay on political diversity that got me started down this road, and which documented the rapid political purification of psychology since the 1990s.

And we say it succinctly on the Welcome page of Heterodox Academy:

Welcome to our site. We are professors who want to improve our academic disciplines. Many of us have written about a particular problem: the loss or lack of “viewpoint diversity.” It’s what happens when the great majority of people in a field think the same way on important issues that are not really settled matters of fact. We don’t want viewpoint diversity on whether the Earth is round versus flat. But do we want everyone to share the same presuppositions when it comes to the study of race, class, gender, inequality, evolution, or history? Can research that emerges from an ideologically uniform and orthodox academy be as good, useful, and reliable as research that emerges from a more heterodox academy?

Science is among humankind’s most successful institutions not because scientists are so rational and open minded but because scholarly institutions work to counteract the errors and flaws of what are, after all, normal cognitively challenged human beings. We academics are generally biased toward confirming our own theories and validating our favored beliefs. But as long as we can all count on the peer review process and a vigorous post-publication peer debate process, we can rest assured that most obvious errors and biases will get called out. Researchers who have different values, political identities, and intellectual presuppositions and who disagree with published findings will run other studies, obtain opposing results, and the field will gradually sort out the truth.

Unless there is nobody out there who thinks differently. Or unless the few such people shrink from speaking up because they expect anger in response, even ostracism. That is what sometimes happens when orthodox beliefs and “sacred” values are challenged.

Our concern at Heterodox Academy is very simple. It was expressed perfectly in 1859 by John Stuart Mill, in On Liberty:

He who knows only his own side of the case knows little of that. His reasons may be good, and no one may have been able to refute them. But if he is equally unable to refute the reasons on the opposite side, if he does not so much as know what they are, he has no ground for preferring either opinion… Nor is it enough that he should hear the opinions of adversaries from his own teachers, presented as they state them, and accompanied by what they offer as refutations. He must be able to hear them from persons who actually believe them…he must know them in their most plausible and persuasive form.

Holbo seems to think that if you were to start with a campus faculty entirely composed of non-authoritarian progressives (people like Nick Kristof or Barack Obama, who praise the importance of dissent), and then you added in some authoritarian progressives, who punish dissent on their most sacred issues, you would improve the campus ecology. Well, Holbo is right that you’d be adding a kind of diversity, but it’s one that is often hostile to other viewpoints. Mill and I and the rest of Heterodox Academy think it would be better to expose students—and professors—to people who hold views across the political spectrum, especially if you can do it within an institution that fosters a sense of community and norms of civility. We don’t care about balance. We don’t need every view to be represented. We just want to break up orthodoxy. Is that illogical?

Read More

How the Democrats Can Use Moral Foundations Theory Against Trump

Tom Edsall of the New York Times just published a column giving responses from me and other professors and political strategists to this question: Given the many claims and promises Donald Trump has made which will be impossible to fulfill, how should the Democrats refute them? (E.g., Trump’s claim that he would grow the economy by 6% per year, or end birthright citizenship.) Edsall printed the best parts of my response, but as long as I have a blog where I can post my entire response, here it is:

Hi Tom,

Your question presupposes that the Democrats should be trying to create better arguments. Yes, they should, but that is not the place to start. One of the basic principles of psychology is that the mind is divided into parts that sometimes conflict, like a small rider (conscious verbal reasoning) sitting atop a large elephant (the other 98% of mental processes, which are automatic and intuitive). The elephant is much stronger, and is quite smart in its own way. If the elephant wants to walk to the right, it’s going to, and there’s no point in trying to persuade the rider to steer to the left. In fact, the elephant really runs the show, and the rider’s job is really to help the elephant get where it wants to go. This is why all of us are so brilliant at finding post-hoc justifications for whatever we want to believe. And this is why, in matters of politics and morality, you must speak to the elephant first. Trump did this brilliantly in the Republican primary, and in his convention speech. But how will he do when he appeals to people in the broader electorate?

I think the Democrats need to tell a story about Trump that activates deep and powerful moral intuitions, so that vast numbers of voters find their elephants moving away from Trump. At that point, good arguments will stick.

I think there are two main approaches. The first links to deep moral intuitions about fairness versus cheating and exploitation. Trump presents himself as a successful businessman. But a good businessman creates positive-sum interactions. He leaves a long trail of satisfied customers who want to buy from him again, and a long trail of satisfied partners who want to work with him again. Trump has not done this. He thinks about everything as a zero sum interaction, which he usually wins — and therefore the person who dealt with him loses. I think the Democrats should give voice to a long parade of people — former customers and partners — who deeply regret dealing with Trump. Trump cheats, exploits, deceives. Trump is a con-man, and we are his biggest mark yet. Don’t let him turn us all into suckers.

The second approach is to link to moral intuitions about loyalty, authority, and sanctity. These are the moral foundations that authoritarians and ultra-nationalists generally appeal to, and Trump sure did this in his convention speech. But these can be turned against him too. Trump talks about patriotism (a form of loyalty), but he seems to be pals with one of our main adversaries (Putin) while telling our friends in the Baltics that we may not defend them. In these ways he brings shame to America and weakens our stature among our friends. The moral importance of authority is in part that it creates order, and Trump talks a great deal about law and order, yet he is the chaos candidate who will throw America into constant constitutional crises, throw the world into recession, and throw our alliances into disarray. The moral importance of sanctity is that it brings dignity and exaltation to people, places, and institutions that can unite people who worship things in common. The psychology of sacredness evolved as part of our religious nature, but people use the same psychology toward kings, the constitution, national heroes, and, to a decreasing degree, to the American presidency. Trump degrades it all with his crassness, his obscene language, his fear-mongering and his inability to offer soaring rhetoric. What a contrast with Washington, Jefferson, Lincoln, and Reagan.

So I don’t think the Democrats should focus on raising doubts about his specific promises at this point. They should focus on linking Trump to violations of deeply held moral intuitions. If they can first speak persuasively to voters’ elephants, they will then find it much easier to speak to the reason-based riders, and to raise doubts about the specific things Trump has promised.

Read MoreThe politics of disgust animated for the age of Trump

How does disgust influence modern political behavior? I’ve been studying disgust as a moral emotion since I was a graduate student at the University of Pennsylvania, working with Paul Rozin. It’s a fascinating emotion, lurking behind most of the divisive social issues in the American culture war, from abortion through flag burning, gay marriage, and now trans-gender bathroom access. My colleagues and I have found that social conservatives are higher on “disgust sensitivity” than are progressives and libertarians, and we’ve found that people’s scores on the “sanctity” foundation of the Moral Foundations Scale is a powerful predictor of their attitudes on many political issues, even after you partial out their self-placement on the left-right dimension.

The role of disgust in politics is especially important in 2016 as Donald Trump talks more about disgust than any major political figure since, well, some 20th century figures that were concerned about guarding the purity of their nation and ethnic stock. Studying disgust can help you understand Donald Trump and some portion of his political appeal. I haven’t studied European right-wing movements, but I’ve seen hints that disgust plays a role in many of them as well. Anyone interested in the psychology of authoritarianism should learn a bit about disgust.

In 2013 I gave a talk on the psychology of disgust and politics at the Museum of Sex, in New York City, hosted by Reason, so the audience was mostly composed of libertarians. An artist, Matthew Drake, has just taken a portion of that talk – on the evolution of disgust and its links to politics – and animated it using the RSA whiteboard technique. I think he did a great job; see for yourself below.

(Note that there is no sound for the first 28 seconds)

Read More

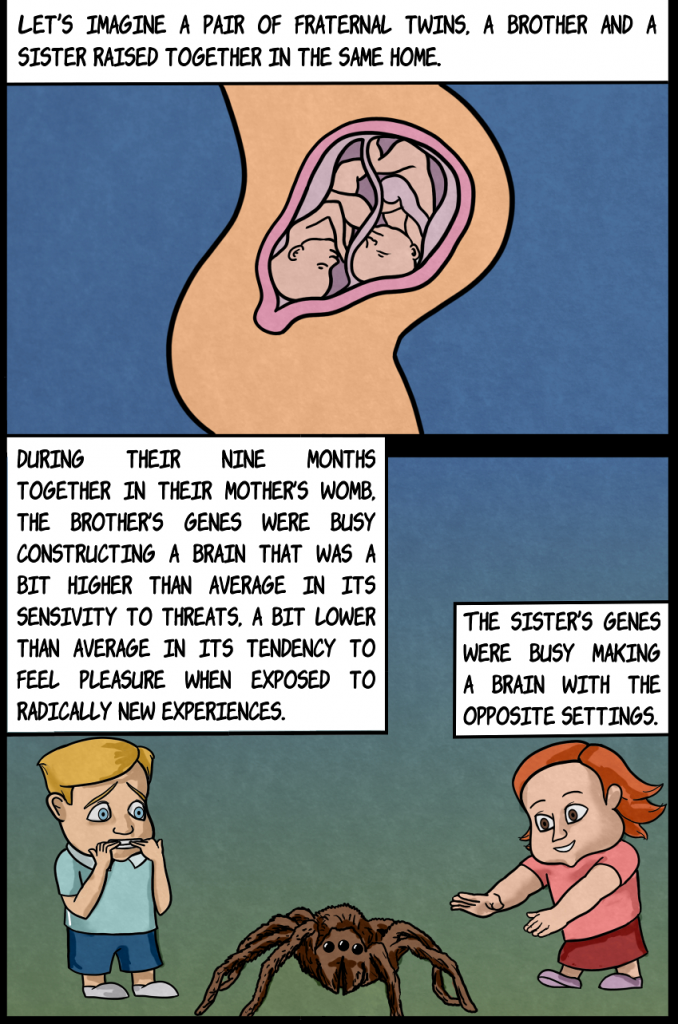

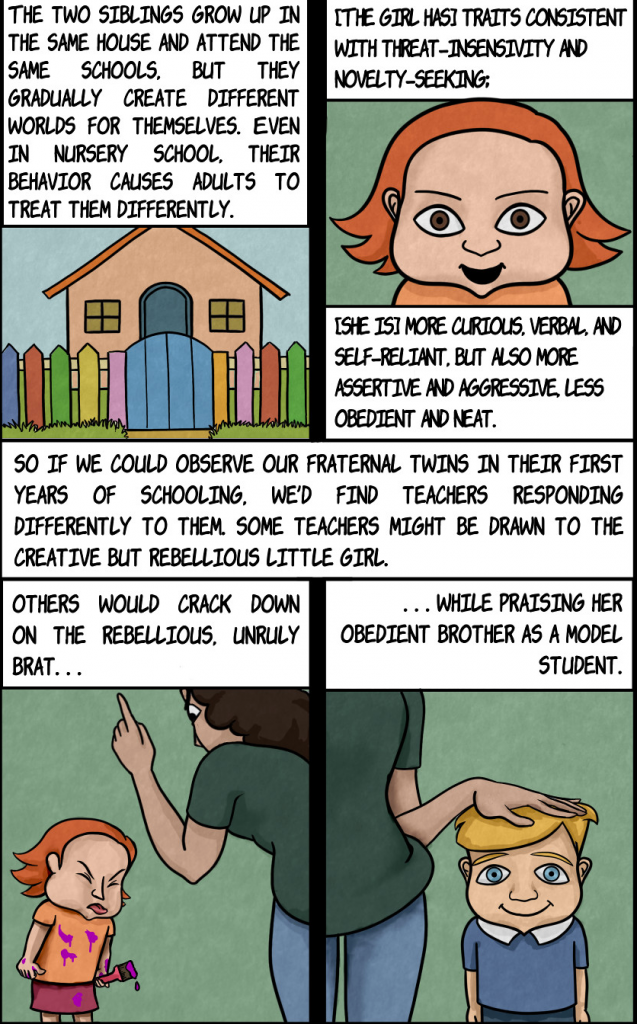

Where political identities come from, in one cartoon

A Brazilian law student — Hugo Freitas — read The Righteous Mind and turned a section of chapter 12 into a cartoon. He takes the exact text and illustrates it to show how two siblings can grow up to become so different in their political views. Here are the first two panels; you can click here to go to his site to see the full story.

Please click here to go to his site to see the remaining 6 panels.

When Freitas wrote to me to show the the cartoon, the back story of the cartoon that he told me was as interesting as the cartoon itself. I invited him to publish that story here:

What inspired me to make this comic was my experience at law school at the Federal University of Minas Gerais, a place that has historically had a reputation for its political activism. Soon after arriving, I realized that the students there saw themselves as being divided into two tribes, acting as left and right in local politics.

One faction is called the tilelês, a word that originally carried a meaning similar to hippie. The other is called coxinhas, originally a São Paulo slang word that can be best translated as preppy.

As I read The Righteous Mind, I found that many passages sounded like a good description of what was going on when our two tribes quarreled over internal policy issues. At times the coxinhas would appeal to the Sanctity foundation (e.g. outsiders were coming into our premises to use drugs and this was morally polluting our college) or demand in-group loyalty and protective measures for our community (e.g. calls for implementing access turnstiles to keep outsiders out; this was bad for the outsiders, but good for the security of the in-group; it’s uncannily similar to the political issue of immigration) or demand respect for the Authority foundation (e.g. condemning students who made graffiti on walls to convey political messages, because they were disobeying the laws that forbid writing on walls).

In contrast, the tilelês would never rely on anything other than Care and Liberty as moral foundations. For example, they would say that the only reason people wanted to keep outsiders out was due to racism, as many of them were black (Care foundation), and they thought that ours was a public university and hence should be open for anyone to enter (a cosmopolitan view, in contrast to the parochialism of the other tribe). They would say that there was nothing wrong with anyone using drugs wherever (Liberty foundation). They would say that enforcing the prohibition against graffiti was an authoritarian act of silencing people’s expression (Liberty foundation again). And they would crack down on professors and members of the administration who made politically incorrect remarks, sometimes resorting to graffiti to denounce them (Care foundation, while actively rejecting the Authority foundation).

As I began to look into the literature about the psychological differences between conservatives and progressives, I was even more excited, because the theories also seemed to explain obvious behavioral differences between the tilelês and the coxinhas that had seemingly nothing to do with politics, such as their clothing style and entertainment choices. For example, their fashion preferences (coxinhas adopt a conventional look, tilelês like it outside the mainstream), their entertainment choices (coxinhas go to the most traditional and most expensive nightclubs, tilelês prefer more alternative venues) or their academic preferences (tilelês like propaedeutics such as Anthropology or Sociology, whereas coxinhas are more practical and tend to see no interest in such courses, as they won’t help them make money, which is what they’re in college for). All of this suggests that tilelês are higher in Openness to Experience, as the theory predicts.

While learning about all this was fascinating in itself, I also found that it could be put into practical use in perhaps helping heal the divide. Our division into moral tribes has broken friendships and even led to physical segregation: an informal collective agreement was made so that students pertaining to different tribes would enroll at separate classes. Professors have noticed the difference: they know which class will passively listen and which one will constantly interrupt them to question the implication of what they say for the issues faced by social minorities.

Can we all get along?

Thank you, Hugo! This is a great service to other readers, and to law students. American law schools are getting quite politicized as well (the tilelês generally have the upper hand). Educational institutions in many countries get more polarized, turning out a new generation of professionals who may have more trouble working across political divisions than did previous generations.

Read More