Where political identities come from, in one cartoon

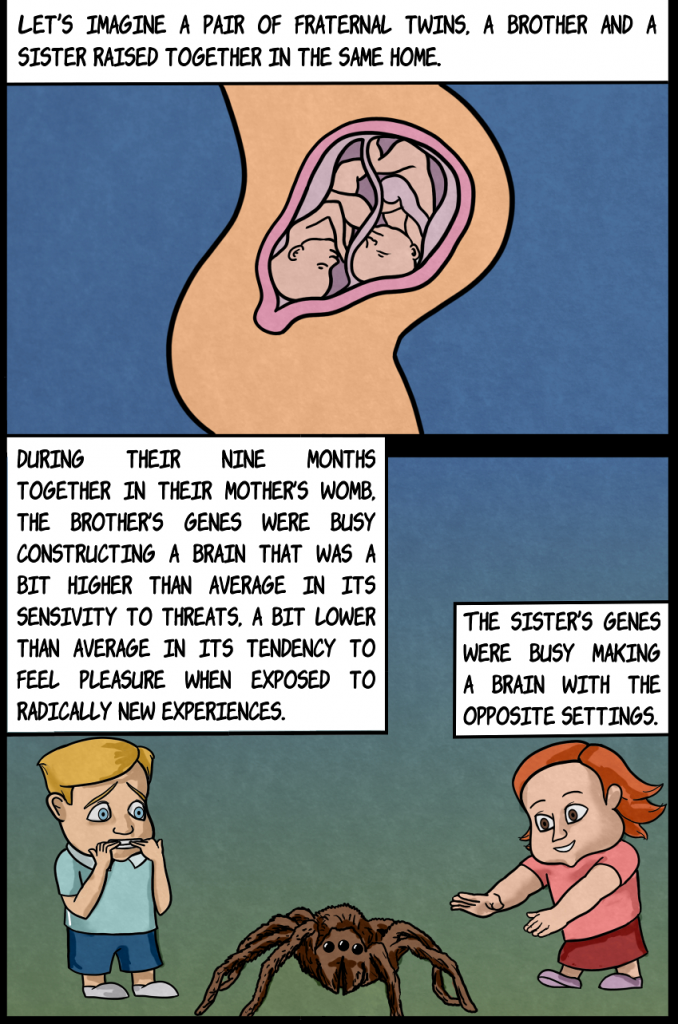

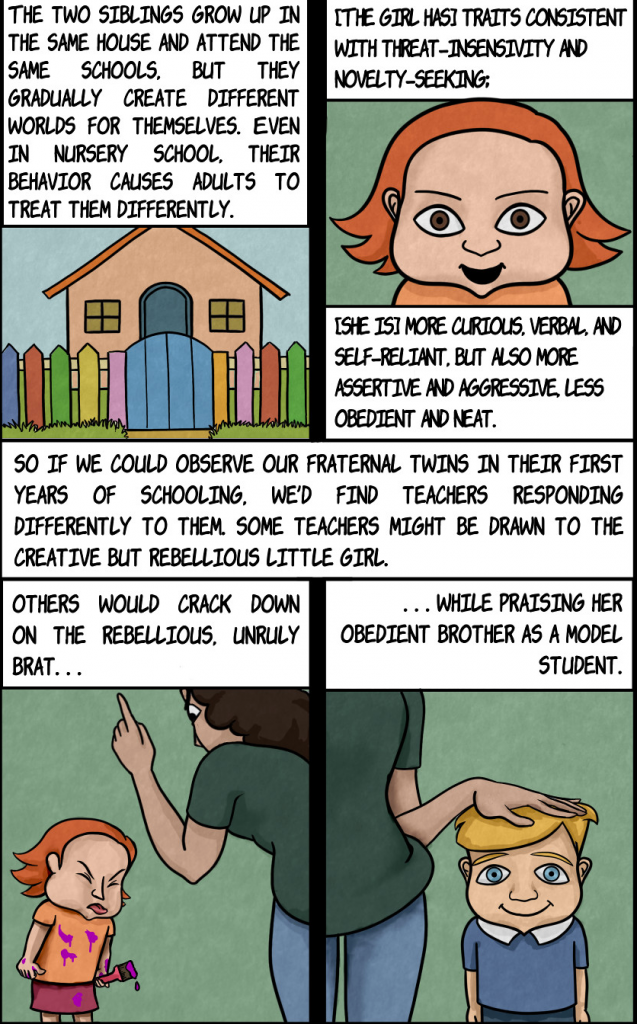

A Brazilian law student — Hugo Freitas — read The Righteous Mind and turned a section of chapter 12 into a cartoon. He takes the exact text and illustrates it to show how two siblings can grow up to become so different in their political views. Here are the first two panels; you can click here to go to his site to see the full story.

Please click here to go to his site to see the remaining 6 panels.

When Freitas wrote to me to show the the cartoon, the back story of the cartoon that he told me was as interesting as the cartoon itself. I invited him to publish that story here:

What inspired me to make this comic was my experience at law school at the Federal University of Minas Gerais, a place that has historically had a reputation for its political activism. Soon after arriving, I realized that the students there saw themselves as being divided into two tribes, acting as left and right in local politics.

One faction is called the tilelês, a word that originally carried a meaning similar to hippie. The other is called coxinhas, originally a São Paulo slang word that can be best translated as preppy.

As I read The Righteous Mind, I found that many passages sounded like a good description of what was going on when our two tribes quarreled over internal policy issues. At times the coxinhas would appeal to the Sanctity foundation (e.g. outsiders were coming into our premises to use drugs and this was morally polluting our college) or demand in-group loyalty and protective measures for our community (e.g. calls for implementing access turnstiles to keep outsiders out; this was bad for the outsiders, but good for the security of the in-group; it’s uncannily similar to the political issue of immigration) or demand respect for the Authority foundation (e.g. condemning students who made graffiti on walls to convey political messages, because they were disobeying the laws that forbid writing on walls).

In contrast, the tilelês would never rely on anything other than Care and Liberty as moral foundations. For example, they would say that the only reason people wanted to keep outsiders out was due to racism, as many of them were black (Care foundation), and they thought that ours was a public university and hence should be open for anyone to enter (a cosmopolitan view, in contrast to the parochialism of the other tribe). They would say that there was nothing wrong with anyone using drugs wherever (Liberty foundation). They would say that enforcing the prohibition against graffiti was an authoritarian act of silencing people’s expression (Liberty foundation again). And they would crack down on professors and members of the administration who made politically incorrect remarks, sometimes resorting to graffiti to denounce them (Care foundation, while actively rejecting the Authority foundation).

As I began to look into the literature about the psychological differences between conservatives and progressives, I was even more excited, because the theories also seemed to explain obvious behavioral differences between the tilelês and the coxinhas that had seemingly nothing to do with politics, such as their clothing style and entertainment choices. For example, their fashion preferences (coxinhas adopt a conventional look, tilelês like it outside the mainstream), their entertainment choices (coxinhas go to the most traditional and most expensive nightclubs, tilelês prefer more alternative venues) or their academic preferences (tilelês like propaedeutics such as Anthropology or Sociology, whereas coxinhas are more practical and tend to see no interest in such courses, as they won’t help them make money, which is what they’re in college for). All of this suggests that tilelês are higher in Openness to Experience, as the theory predicts.

While learning about all this was fascinating in itself, I also found that it could be put into practical use in perhaps helping heal the divide. Our division into moral tribes has broken friendships and even led to physical segregation: an informal collective agreement was made so that students pertaining to different tribes would enroll at separate classes. Professors have noticed the difference: they know which class will passively listen and which one will constantly interrupt them to question the implication of what they say for the issues faced by social minorities.

Can we all get along?

Thank you, Hugo! This is a great service to other readers, and to law students. American law schools are getting quite politicized as well (the tilelês generally have the upper hand). Educational institutions in many countries get more polarized, turning out a new generation of professionals who may have more trouble working across political divisions than did previous generations.

Read More