How not to improve the moral ecology of campus

Writing at the philosophy/politics blog Crooked Timber, philosopher John Holbo offers a critique of my arguments about the need for more viewpoint diversity on campus. Holbo believes that my arguments contain an internal logical contradiction, which he explains like this:

Haidt is highly bothered about two problems he sees with liberalism on campus – and in other environments in which lefties predominate….

1) An unbalanced moral ecology. Allegedly liberals have a thinner base of values, whereas conservatives have a broader one. Everyone, liberal and conservative alike, is ok with care/no harm/liberty – although liberals are stronger on these. Conservatives are much stronger on the loyalty/authority/purity axis, since allegedly liberals are weak-to-negligible here…. So: not enough conservatives in liberal environments to ensure a flexible, broad base of values. How illiberal!

2) Political correctness. Haidt has a real bug in his ear about this one.

The logic problem is this. If 2) is a problem, 1) is necessarily solved. And if solving 2) is important, then the proposed solution to 1) is wrong (or at least no reason has been given to suppose it is right).

Holbo’s claim is that if PC is really a problem, then that necessarily means that universities are full of people who are…

“shooting through the roof along the loyalty/authority/purity axis. Because that’s what PC is. An authoritarian insistence on ‘safe spaces’ and language policing, trigger warnings and other stuff.”

But if campuses are truly full of left-wing authoritarians (he says), then there’s no imbalance in the moral ecology, because all of the moral foundations are represented.

But there’s a big problem with Holbo’s argument. I don’t say that the problem on campus is that there’s an absence of one or more foundations. I say, over and over again, that the decline in political diversity has led to a loss of institutionalized disconfirmation. This was our argument in the BBS essay on political diversity that got me started down this road, and which documented the rapid political purification of psychology since the 1990s.

And we say it succinctly on the Welcome page of Heterodox Academy:

Welcome to our site. We are professors who want to improve our academic disciplines. Many of us have written about a particular problem: the loss or lack of “viewpoint diversity.” It’s what happens when the great majority of people in a field think the same way on important issues that are not really settled matters of fact. We don’t want viewpoint diversity on whether the Earth is round versus flat. But do we want everyone to share the same presuppositions when it comes to the study of race, class, gender, inequality, evolution, or history? Can research that emerges from an ideologically uniform and orthodox academy be as good, useful, and reliable as research that emerges from a more heterodox academy?

Science is among humankind’s most successful institutions not because scientists are so rational and open minded but because scholarly institutions work to counteract the errors and flaws of what are, after all, normal cognitively challenged human beings. We academics are generally biased toward confirming our own theories and validating our favored beliefs. But as long as we can all count on the peer review process and a vigorous post-publication peer debate process, we can rest assured that most obvious errors and biases will get called out. Researchers who have different values, political identities, and intellectual presuppositions and who disagree with published findings will run other studies, obtain opposing results, and the field will gradually sort out the truth.

Unless there is nobody out there who thinks differently. Or unless the few such people shrink from speaking up because they expect anger in response, even ostracism. That is what sometimes happens when orthodox beliefs and “sacred” values are challenged.

Our concern at Heterodox Academy is very simple. It was expressed perfectly in 1859 by John Stuart Mill, in On Liberty:

He who knows only his own side of the case knows little of that. His reasons may be good, and no one may have been able to refute them. But if he is equally unable to refute the reasons on the opposite side, if he does not so much as know what they are, he has no ground for preferring either opinion… Nor is it enough that he should hear the opinions of adversaries from his own teachers, presented as they state them, and accompanied by what they offer as refutations. He must be able to hear them from persons who actually believe them…he must know them in their most plausible and persuasive form.

Holbo seems to think that if you were to start with a campus faculty entirely composed of non-authoritarian progressives (people like Nick Kristof or Barack Obama, who praise the importance of dissent), and then you added in some authoritarian progressives, who punish dissent on their most sacred issues, you would improve the campus ecology. Well, Holbo is right that you’d be adding a kind of diversity, but it’s one that is often hostile to other viewpoints. Mill and I and the rest of Heterodox Academy think it would be better to expose students—and professors—to people who hold views across the political spectrum, especially if you can do it within an institution that fosters a sense of community and norms of civility. We don’t care about balance. We don’t need every view to be represented. We just want to break up orthodoxy. Is that illogical?

Read More

How the Democrats Can Use Moral Foundations Theory Against Trump

Tom Edsall of the New York Times just published a column giving responses from me and other professors and political strategists to this question: Given the many claims and promises Donald Trump has made which will be impossible to fulfill, how should the Democrats refute them? (E.g., Trump’s claim that he would grow the economy by 6% per year, or end birthright citizenship.) Edsall printed the best parts of my response, but as long as I have a blog where I can post my entire response, here it is:

Hi Tom,

Your question presupposes that the Democrats should be trying to create better arguments. Yes, they should, but that is not the place to start. One of the basic principles of psychology is that the mind is divided into parts that sometimes conflict, like a small rider (conscious verbal reasoning) sitting atop a large elephant (the other 98% of mental processes, which are automatic and intuitive). The elephant is much stronger, and is quite smart in its own way. If the elephant wants to walk to the right, it’s going to, and there’s no point in trying to persuade the rider to steer to the left. In fact, the elephant really runs the show, and the rider’s job is really to help the elephant get where it wants to go. This is why all of us are so brilliant at finding post-hoc justifications for whatever we want to believe. And this is why, in matters of politics and morality, you must speak to the elephant first. Trump did this brilliantly in the Republican primary, and in his convention speech. But how will he do when he appeals to people in the broader electorate?

I think the Democrats need to tell a story about Trump that activates deep and powerful moral intuitions, so that vast numbers of voters find their elephants moving away from Trump. At that point, good arguments will stick.

I think there are two main approaches. The first links to deep moral intuitions about fairness versus cheating and exploitation. Trump presents himself as a successful businessman. But a good businessman creates positive-sum interactions. He leaves a long trail of satisfied customers who want to buy from him again, and a long trail of satisfied partners who want to work with him again. Trump has not done this. He thinks about everything as a zero sum interaction, which he usually wins — and therefore the person who dealt with him loses. I think the Democrats should give voice to a long parade of people — former customers and partners — who deeply regret dealing with Trump. Trump cheats, exploits, deceives. Trump is a con-man, and we are his biggest mark yet. Don’t let him turn us all into suckers.

The second approach is to link to moral intuitions about loyalty, authority, and sanctity. These are the moral foundations that authoritarians and ultra-nationalists generally appeal to, and Trump sure did this in his convention speech. But these can be turned against him too. Trump talks about patriotism (a form of loyalty), but he seems to be pals with one of our main adversaries (Putin) while telling our friends in the Baltics that we may not defend them. In these ways he brings shame to America and weakens our stature among our friends. The moral importance of authority is in part that it creates order, and Trump talks a great deal about law and order, yet he is the chaos candidate who will throw America into constant constitutional crises, throw the world into recession, and throw our alliances into disarray. The moral importance of sanctity is that it brings dignity and exaltation to people, places, and institutions that can unite people who worship things in common. The psychology of sacredness evolved as part of our religious nature, but people use the same psychology toward kings, the constitution, national heroes, and, to a decreasing degree, to the American presidency. Trump degrades it all with his crassness, his obscene language, his fear-mongering and his inability to offer soaring rhetoric. What a contrast with Washington, Jefferson, Lincoln, and Reagan.

So I don’t think the Democrats should focus on raising doubts about his specific promises at this point. They should focus on linking Trump to violations of deeply held moral intuitions. If they can first speak persuasively to voters’ elephants, they will then find it much easier to speak to the reason-based riders, and to raise doubts about the specific things Trump has promised.

Read MoreThe politics of disgust animated for the age of Trump

How does disgust influence modern political behavior? I’ve been studying disgust as a moral emotion since I was a graduate student at the University of Pennsylvania, working with Paul Rozin. It’s a fascinating emotion, lurking behind most of the divisive social issues in the American culture war, from abortion through flag burning, gay marriage, and now trans-gender bathroom access. My colleagues and I have found that social conservatives are higher on “disgust sensitivity” than are progressives and libertarians, and we’ve found that people’s scores on the “sanctity” foundation of the Moral Foundations Scale is a powerful predictor of their attitudes on many political issues, even after you partial out their self-placement on the left-right dimension.

The role of disgust in politics is especially important in 2016 as Donald Trump talks more about disgust than any major political figure since, well, some 20th century figures that were concerned about guarding the purity of their nation and ethnic stock. Studying disgust can help you understand Donald Trump and some portion of his political appeal. I haven’t studied European right-wing movements, but I’ve seen hints that disgust plays a role in many of them as well. Anyone interested in the psychology of authoritarianism should learn a bit about disgust.

In 2013 I gave a talk on the psychology of disgust and politics at the Museum of Sex, in New York City, hosted by Reason, so the audience was mostly composed of libertarians. An artist, Matthew Drake, has just taken a portion of that talk – on the evolution of disgust and its links to politics – and animated it using the RSA whiteboard technique. I think he did a great job; see for yourself below.

(Note that there is no sound for the first 28 seconds)

Read More

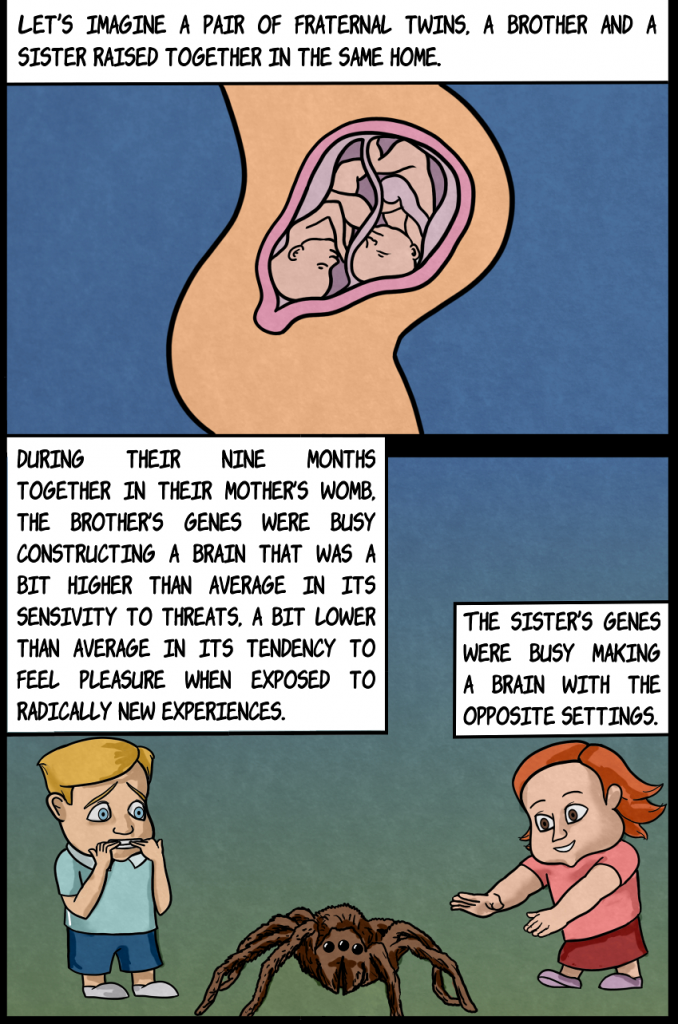

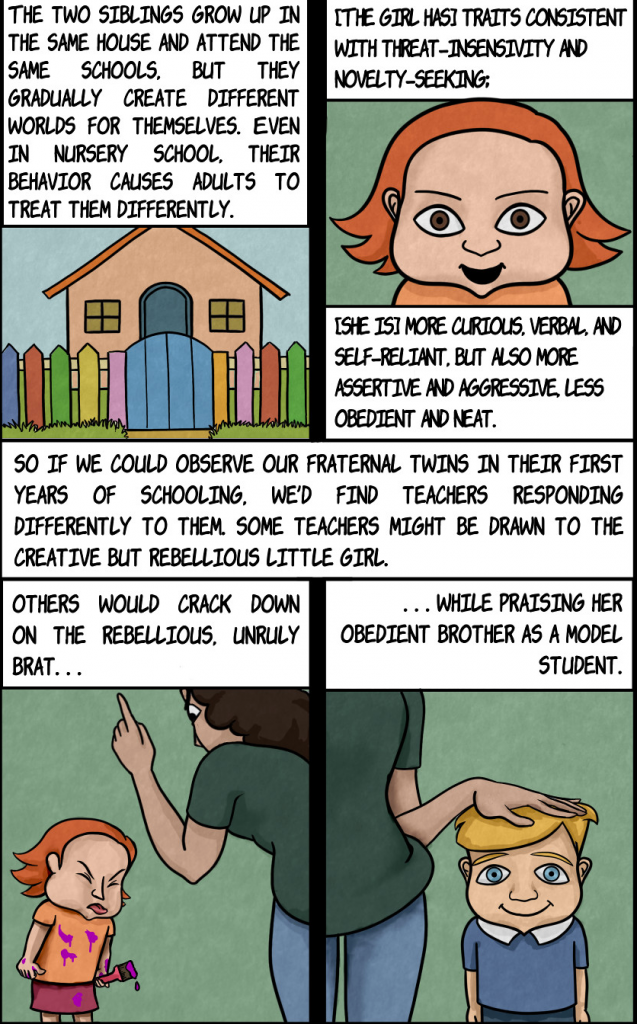

Where political identities come from, in one cartoon

A Brazilian law student — Hugo Freitas — read The Righteous Mind and turned a section of chapter 12 into a cartoon. He takes the exact text and illustrates it to show how two siblings can grow up to become so different in their political views. Here are the first two panels; you can click here to go to his site to see the full story.

Please click here to go to his site to see the remaining 6 panels.

When Freitas wrote to me to show the the cartoon, the back story of the cartoon that he told me was as interesting as the cartoon itself. I invited him to publish that story here:

What inspired me to make this comic was my experience at law school at the Federal University of Minas Gerais, a place that has historically had a reputation for its political activism. Soon after arriving, I realized that the students there saw themselves as being divided into two tribes, acting as left and right in local politics.

One faction is called the tilelês, a word that originally carried a meaning similar to hippie. The other is called coxinhas, originally a São Paulo slang word that can be best translated as preppy.

As I read The Righteous Mind, I found that many passages sounded like a good description of what was going on when our two tribes quarreled over internal policy issues. At times the coxinhas would appeal to the Sanctity foundation (e.g. outsiders were coming into our premises to use drugs and this was morally polluting our college) or demand in-group loyalty and protective measures for our community (e.g. calls for implementing access turnstiles to keep outsiders out; this was bad for the outsiders, but good for the security of the in-group; it’s uncannily similar to the political issue of immigration) or demand respect for the Authority foundation (e.g. condemning students who made graffiti on walls to convey political messages, because they were disobeying the laws that forbid writing on walls).

In contrast, the tilelês would never rely on anything other than Care and Liberty as moral foundations. For example, they would say that the only reason people wanted to keep outsiders out was due to racism, as many of them were black (Care foundation), and they thought that ours was a public university and hence should be open for anyone to enter (a cosmopolitan view, in contrast to the parochialism of the other tribe). They would say that there was nothing wrong with anyone using drugs wherever (Liberty foundation). They would say that enforcing the prohibition against graffiti was an authoritarian act of silencing people’s expression (Liberty foundation again). And they would crack down on professors and members of the administration who made politically incorrect remarks, sometimes resorting to graffiti to denounce them (Care foundation, while actively rejecting the Authority foundation).

As I began to look into the literature about the psychological differences between conservatives and progressives, I was even more excited, because the theories also seemed to explain obvious behavioral differences between the tilelês and the coxinhas that had seemingly nothing to do with politics, such as their clothing style and entertainment choices. For example, their fashion preferences (coxinhas adopt a conventional look, tilelês like it outside the mainstream), their entertainment choices (coxinhas go to the most traditional and most expensive nightclubs, tilelês prefer more alternative venues) or their academic preferences (tilelês like propaedeutics such as Anthropology or Sociology, whereas coxinhas are more practical and tend to see no interest in such courses, as they won’t help them make money, which is what they’re in college for). All of this suggests that tilelês are higher in Openness to Experience, as the theory predicts.

While learning about all this was fascinating in itself, I also found that it could be put into practical use in perhaps helping heal the divide. Our division into moral tribes has broken friendships and even led to physical segregation: an informal collective agreement was made so that students pertaining to different tribes would enroll at separate classes. Professors have noticed the difference: they know which class will passively listen and which one will constantly interrupt them to question the implication of what they say for the issues faced by social minorities.

Can we all get along?

Thank you, Hugo! This is a great service to other readers, and to law students. American law schools are getting quite politicized as well (the tilelês generally have the upper hand). Educational institutions in many countries get more polarized, turning out a new generation of professionals who may have more trouble working across political divisions than did previous generations.

Read More

Are moral foundations heritable? Probably

Are moral foundation scores heritable? A new paper by Kevin Smith et al. has tested moral foundations theory in a sample of Australian twins and found that moral foundations are neither heritable nor stable over time. The authors summarized MFT fairly, and they used a research design that is appropriate for the questions they asked, but with one major flaw: They improvised an ultra-short measure of moral foundations (around 2008) that turned out to be so poor that they essentially have no measure of moral foundations at time 1. Then at time 2 (around 2010), they used a better measure when the MFQ20 became available. As I show below, little can be concluded about heritability and nothing can be concluded about stability from their data.

Citation: Smith, K. B., Alford, J. R., Hibbing, J. R., Martin, N. G., & Hatemi, P. K. (2016). Intuitive Ethics and Political Orientations: Testing Moral Foundations as a Theory of Political Ideology. American Journal of Political Science. doi: 10.1111/ajps.12255

Abstract: Originally developed to explain cultural variation in moral judgments, moral foundations theory (MFT) has become widely adopted as a theory of political ideology. MFT posits that political attitudes are rooted in instinctual evaluations generated by innate psychological modules evolved to solve social dilemmas. If this is correct, moral foundations must be relatively stable dispositional traits, changes in moral foundations should systematically predict consequent changes in political orientations, and, at least in part, moral foundations must be heritable. We test these hypotheses and find substantial variability in individual-level moral foundations across time, and little evidence that these changes account for changes in political attitudes. We also find little evidence that moral foundations are heritable. These findings raise questions about the future of MFT as a theory of ideology.

Below is the signed (non-anonymous) review I submitted in August of 2014, when I was asked to evaluate a previous version of the manuscript for a different journal. The authors seem to have added some new datasets that use the MFQ 30 (on non-twins) to examine the factor structure of the MFQ, but there is nothing they can do to fix the measurement problems from wave 1 of their twin study. I have put in bold the main problems with the article, so you can get the point by just reading those sections.

I did not know who the authors were, in 2014. Now that I know, I can add that I am a fan of their work and their general approach integrating to integrating biology, psychology, and political science. We all agree that individuals are biologically and genetically “predisposed” to find certain political ideas more agreeable, but that these predispositions are not predeterminations — life experiences and learning shape political identities as they develop beyond those predispositions. So we all agree that something about political identity is heritable. (To see our main statement on Moral Foundations Theory, evolution, and personality, click here.)

This paper has the potential to be very important. It is always a big deal when a psychological construct gets is first heritability data, particularly when that construct is related to highly visible recent developments on the heritability of ideology. It is also the case that this paper is well argued and well developed theoretically. The authors have read my work closely and summarized it fairly with a few small exceptions.

The entire question of publication, however, turns on whether the authors have adequately measured moral foundations. If the measures they use to quantify the moral foundations in each participant are nearly as good as the measures they use to quantify ideology, then the inferences they make about causal directions and heritability are on solid ground. But if the two-item measures of moral foundations used here are much less reliable than the 23 item measure of ideology, then of course it will appear that ideology is stable and heritable (if indeed it is heritable), while moral foundations will appear unstable and unheritable (even if they are heritable).

I believe that the 2-item measures used in this paper to assign scores on moral foundations are extremely poor measures, based on my own data, on nationally representative American data, and on the authors’ reported data.

Here’s the main problem: My colleagues and I have examined scales of varying lengths, and concluded that 20 items is the shortest MFQ that we are willing to endorse. We base this conclusion on what we think was an innovative analysis. In Graham, Nosek et al. 2011, the paper that presented and validated the MFQ-30, we conducted a variety of tests of reliability and validity. We began with our original 40 item scale, consisting of 20 “relevance” items – 4 for each of the 5 foundations, and 20 “judgment” items, consisting of 4 statements for each of the 5 foundations. We then asked how much we would lose, in terms of the scale’s ability to predict other scales (as markers of external validity) if we shortened the scale. We found that nothing is lost when we move down from 40 to 30 items, dropping the worst 2 items for each foundation (one relevance, and one judgment item). However, dropping from 30 to 20 items produces a moderate loss, and dropping from 20 to 10 produces a big loss in predictive validity. We therefore endorsed the MFQ-30 as our main measure of the moral foundations, and we also offered the MFQ-20 for cases in which researchers need the absolute shortest form they can get away with. However, on our website, MoralFoundations.org, we specifically say this:

“If you must have a shorter version, you can use the MFQ20 (a 20 item version of the MFQ, with alphas that are slightly lower and with less breadth of conceptual coverage)… Please use the MFQ30 if at all possible. It’s hard to get good measurement with just 4 items per foundation!”

Unfortunately, the current authors used just 10 items – a mere 2 items per foundation. To make matters worse, they chose the format that is more abstract, further away from moral intuition, and, in our experience, harder for less educated participants to process. As we say in our 2011 paper validating the MFQ:

“we wanted to supplement the abstract relevance assessments—which, as self-theories about how one makes moral judgments, may be inaccurate with regard to actual moral judgments (Nisbett & Wilson, 1977)—with contextualized items that could more directly gauge actual moral judgments…. the Relevance subscale may better assess explicit theories about what is morally relevant, and the Judgments subscale may better assess actual use of moral foundations in judgment.”

To make matters even worse still, three of the ten items they chose happen to be among the worst of our 40 original items – they are items we don’t even include in the MFQ30, because they reduced (or did not contribute to) reliability. The items are “harmed” “affected your group,” and “fulfilled duties of his or her role.” So three of the five subscales in Wave 1 are essentially using a single valid item to assess foundation scores.

To examine the matter empirically, I found an old database from 2008 that had data from our original 40 item scale, including all 10 of the items used by the present authors. The dataset had 28,596 participants who completed the MFQ40, mostly from the USA, followed by Canada, UK, and Australia. I then examined how well each of the 5 foundation subscales do in terms of reliability and also correlation with self-described political ideology (1=very liberal, 7 = very conservative). I computed these values for the full MFQ (with 6 items per scale), as this is our baseline, or best measure of the constructs. Those numbers appear in the first data column, below. You can see that reliability is generally good (average alpha = .74), and the correlations with ideology are robust (average absolute value = .45)

I then examined how much these numbers fall off when the scale is shortened to the MFQ-20, using the items that we endorsed. As you can see, the dropoff is slight, which validates our choice of items for the MFQ20. Finally, I examined how these numbers fall off when the scale is shortened to the exact 10 items used in Wave 1 in the current study. The dropoff is large. Reliability plummets to .532, and correlations with ideology plummet to r=.286.

2008 Megafile with n = 28,596 who took the MFQ40

| 6 item (MFQ-30) | 4-item (MFQ-20) | 2 item scale used in twin study wave 1 | |

| ALPHAS | |||

| Harm | .707 | .679 | .498 |

| Fairness | .690 | .715 | .473 |

| Ingroup | .702 | .603 | .504 |

| Authority | .751 | .725 | .496 |

| Sanctity | .846 | .811 | .689 |

| Avg alpha | .739 | .706 | .532 |

| CORRELATIONS W. IDEOLOGY | |||

| Harm | -.292 | -.254 | -.190 |

| Fairness | -.427 | -.323 | -.324 |

| Ingroup | .426 | .428 | .177 |

| Authority | .545 | .541 | .380 |

| Sanctity | .536 | .459 | .358 |

| Avg absolute value | .445 | .401 | .286 |

I believe this very poor measurement constitutes an insurmountable defect in the data, and therefore in the argument made in the paper on the basis of the data.

To use an analogy, suppose I wanted to assess the stability of a mountain range over time. I ask my 8 year old son to draw mountain #1, and I take a photograph of Mountain #2. Two years later, I ask my son to draw mountain #1 again, and I take another photograph of Mountain #2. If I compare the images across time, I would conclude that mountain #1 was unstable and highly changeable, whereas Mountain #2 was very stable over time.

I think the same thing is happening here: The present study claims that moral foundations and the MFQ are largely useless, but in fact it’s just a measurement problem. It is not appropriate to demolish a theory when one has not actually measured the central constructs of the theory.

I will now run through the manuscript in order, noting additional points.

–p. 1-6: excellent summary of the theory and its entailments, except as noted below.

–p.2: The claim is made that “any within-individual change in these modules should cause a predictable within-individual change in ideology.” This is false. If people become a bit more compassionate after traveling in a poor country, or a bit more prone to endorse authority after having children, there is no reason to think that one would pick up a change in their self-described ideology or political party. Ideology is a very pronounced social identity; it is socially sticky. It is not just a direct readout of one’s scores on the MFQ.

–p.5, the environmental component of moral development is not just “social reinforcement”. We are not behaviorists. It’s learning of all sorts, some of which is self-constructed, some of which is related to narrative… moral development is complex. People’s moral and political identities can change with no change in their underlying foundations, just as a house can be remodeled with no change to its foundation. It’s just that some kinds of houses/ideology are more likely than chance to be built on some kinds of foundations.

–p.7: its not appropriate to speak of fractions, such as “a fifth of the moral domain”. Care and Fairness support most of the moral domain for just about everybody in the Western world, liberal or conservative. We do not claim that all foundations are equally important or prominent; it’s very difficult to judge percentages anyway.

–p. 7, the affirmative action example is a poor one, because it’s about differing conceptions of fairness, mostly, on both sides.

–p. 8, the social reinforcement point again. Also, “ideology is a stable dispositional trait IN PART because the underlying moral foundations are stable dispositional traits.” People’s self-narrative, local community, public identity, etc contribute to the stability of ideology.

—-p.9, with the above modifications, the 3 assumptions of MFT seem valid to me. I would not expect small changes in moral foundations to be detectible in later ideology, but big changes might. And given that just about everything is heritable to some degree, I would expect moral foundations to be so too, even if they are Level 2 constructs in MacAdams’ terms. So I really like the overall design of this study.

–P. 12: The authors devote considerable effort to showing that their 2-item MFQ subscales have high reliability and predictability, but as I’ve shown above, I think this is unlikely. One of the problems with the “relevance” items is that it uses an unusual item format, which we have found is difficult for less educated participants. They are not asked to tell us what they believe, as in the “judgments” format. They are asked to rate “When you decide whether something is right or wrong, to what extent are the following considerations relevant to your thinking?” We have concluded that this format introduces a large method effect – some people interpret the request in such a way that everything gets a high rating; others interpret it such that they use the middle of the scale, or a broader range of the scale. As evidence of this, we can look at the alpha of the entire scale for each format – all 15 items in the relevance section, compared to all 15 items in the judgment section. There is no reason why the entire relevance section should have a very high alpha – there are 5 subscales, and we don’t want to see that they all correlate with each other. Yet in fact, they do.

Using that same dataset as before, with the whole MFQ40, we find that alpha for the Full set of 20 relevance items is very high, .853, whereas for the 20 judgment items, it is lower, .728. This indicates that there is more of a method artifact in the Relevance section. Some people give really high scores, on all questions, some give lower, on all questions.

When we first started getting nationally representative datasets, in which the education level is lower than at YourMOrals.org, we began to see that this problem is even more acute. We have one nationally representative American sample, collected as part of a paid module added on to the ANES, which included the full MFQ20. We can assume that this dataset is more comparable to the Australian dataset than is data collected at YourMorals.org. When I run the alphas for the two parts there, the relevance section goes up, to .89, whereas the alpha for the judgment section goes down slightly, to .699. If the present study also has an overall alpha for the 10 relevance items that approaches .90, then of course any two items will correlate well, and will produce alphas in the .6 or .7 range.

Again, my point is that the relevance section is just less powerful and reliable as a measure of moral foundations than is the judgments section. This is why we are phasing it out in the new MFQ that we are currently developing. It is not surprising that the authors obtained moderately high alphas on their two-item MFQs, which use just one format that has a big method effect. Their alphas are indeed comparable to the alphas we report in Graham et al, but those alphas reflect subscales with two different item formats (relevance and judgments). Using two item formats was a choice we made to reduce the influence of any one method effect, but it lowers our alphas substantially from the standard personality measure, which uses just a single item format.

–P. 12 Given how poor the measurement of moral foundations is in both waves, particularly wave 1, it is neither surprising nor informative that the authors could not replicate our factor findings.

–P.13. The authors say: “ Overall, then, the MFQ items perform reasonably well psychometrically and replicate the key empirical finding of MFT in two different, though overlapping samples. This gives us confidence that we have a robust platform to test the stability of moral foundations, their impact on political attitudes across time, and their heritability.” I strongly disagree. The moral foundations were simply not measured well enough to conclude anything about stability or causality or heritability. This would explain why the test-retest numbers are so dismal on p. 14.

–P. 15: The authors attempt to validate their 2-item MFQs by analyzing a larger dataset that used MFQ-20. They show that for each foundation, their 2 items correlate with the four items for that foundation in the MFQ-20 quite well, ranging from r=.73 to r=.88. But these correlations seem to reflect part-whole correlations. Of course a score composed of two numbers correlates with a score composed of 4 numbers including those two numbers. To test just how much the part-whole confound could account for their high correlations, I used a random number generator to create 4 columns of 1000 digits each, ranging from 1 to 6, as MFQ items do. I then calculated one score that was the average of the first two columns, and a second score that was the average of all four columns. I then checked the pearson correlation of the two scores. The answer: r = .744. Four columns of random digits give us nearly the same correlations that the authors report as a validation that their 2-item MFQ scores are good proxies for the 4 item MFQ20 scores. They are not good proxies. The authors are therefore incorrect when they say that “These results give us considerable confidence that our MFQ instruments are capturing the lion’s share of the variance that would be picked up by the more contemporary MFQ 20, and that the psychometric properties of our instruments are reliable and consistent.”

The bottom line is that if the authors had used the actual MFQ20 in both waves of their study, they would have obtained good enough measurement to begin drawing conclusions. But because their proxies are demonstrably worse – much worse — than the MFQ20 and MFQ30, their measures of moral foundations simply cannot be compared to their measure of ideology, which we presume is much more accurately measured with a 23 items scale. So even though I think their logic is generally sound while drawing these inferences on pages 13-21, they simply don’t have data that could justify ANY inferences about the moral foundations, or about moral foundations theory.

–P.24: The authors raise some valid concerns about the MFQ: we agree that many of the items are measuring contexualized judgments and attitudes, which we believe are constructed on top of the foundations – they resonate with some people more than others because of underlying psychological differences. But such items do not measure the foundations themselves. We are trying, in our ongoing revision efforts, to create assessment methods that activate more rapid intuitions, and less reasoning.

To conclude, let us look at the authors’ summary or the implications of their work, on p. 23: “Our findings run contrary to assumptions underpinning MFT as it gains increasing traction in the political, psychological and behavioral sciences as theory of ideology. The obvious inference to take from our analyses is that individuals are not born with innate moral value systems, or at a minimum that MFQ instruments do not comprehensively tap into these innate systems.”

I think this inference simply cannot be drawn when, as I have shown, the authors did not use a valid version of the MFQ and do not seem to have accurately measured the key constructs of MFT. Furthermore, all data aside, how likely is their conclusion to be true? What should our prior expectation be? Given that almost every aspect of personality is heritable to some degree, including emotional predispositions such as compassion (which is at the heart of the care foundation), how likely is it that the authors have discovered one of the very few aspects of personality that is not heritable? Is it more likely that moral value predispositions don’t exist, or that they were not measured well in this particular study?

Read MoreThe Moral Foundations of the Presidential Primaries

[This guest post was written by Emily Ekins]

We recently published an essay at Vox titled The Moral Foundations of the 2016 Presidential Primaries. That essay was written for a non-academic audience. In this post we expand on our analyses, detail our methodology, and present expanded graphs and data. Please read that essay first, and see the appendix at the end, which lists the 15 questions we used to assess the various moral foundations.

In this post we present:

1) An expanded Figure 1 for all candidates who received support from more than 35 respondents in the sample[1]

2) An expanded analysis of the Democratic race, showing a version of figure 1 for Democratic voters only, which breaks out Authority, Loyalty, and Sanctity as separate bars (Figure 1-D)

3) An expanded analysis of the Republican race, showing a version of figure 1 for Republican voters only, which breaks out Authority, Loyalty, and Sanctity as separate bars (Figure 1-R)

4) Details about our LOGIT regressions (Table 1-D and Table 1-R)

5) Responses to any questions that come up in response to the Vox essay.

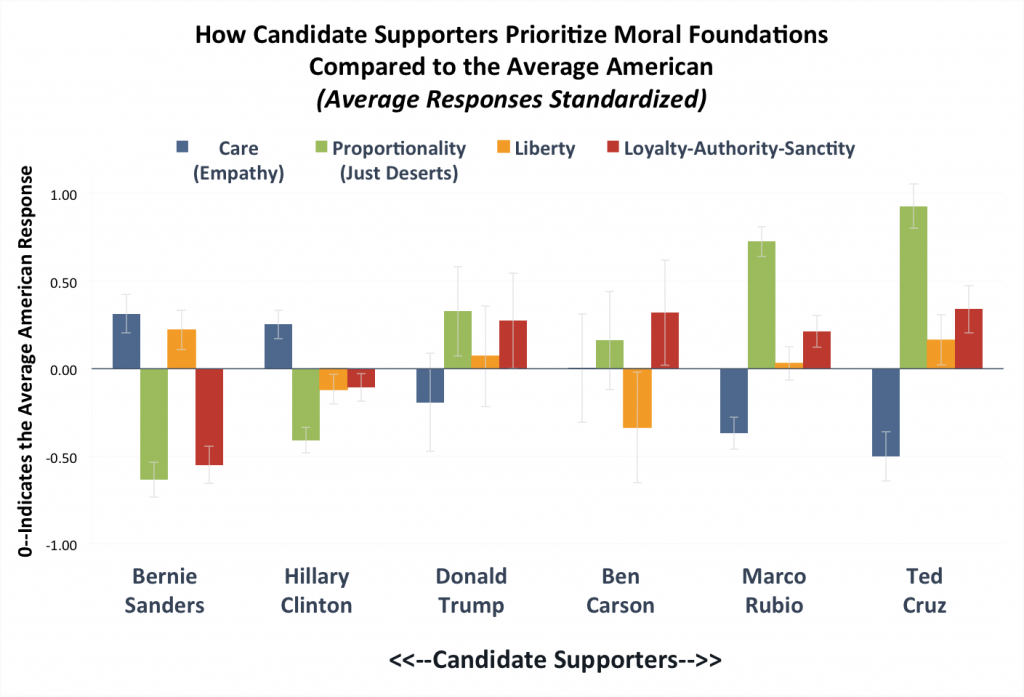

1) Expanded Figure 1 for all candidates

Figure 1(a) shows the top Democratic and Republican candidate vote getters, ordered from left to right according to their supporters’ average reported ideology.

Figure 1(a)

Note: Figure 1(a) reports standardized responses (z-scores), which show how each candidates’ supporters responded to questions about each moral foundation compared to the average American. Y-axis is in standard deviations from the mean. Error bars show 95 percent confidence intervals around the means.

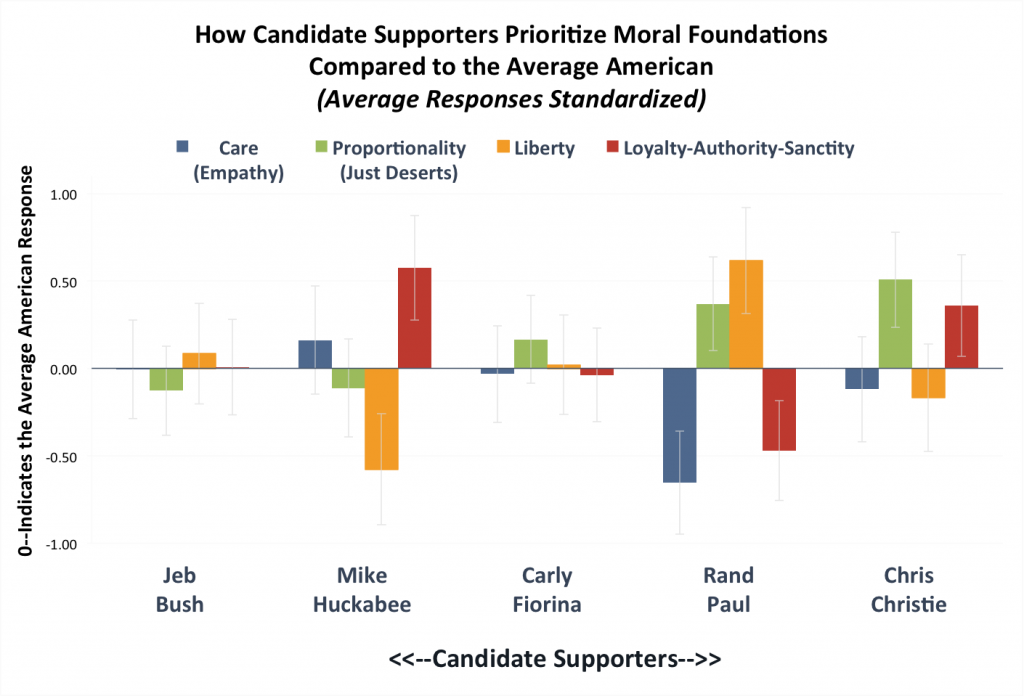

Figure 1(b) shows the 2nd tier candidates also ordered from left to right according to their supporters average reported ideology.

Figure 1(b)

Note: Figure 1(b) reports standardized responses (z-scores), which show how each candidates’ supporters responded to questions about each moral foundation compared to the average American. Y-axis is in standard deviations from the mean. Error bars show 95 percent confidence intervals around the means.

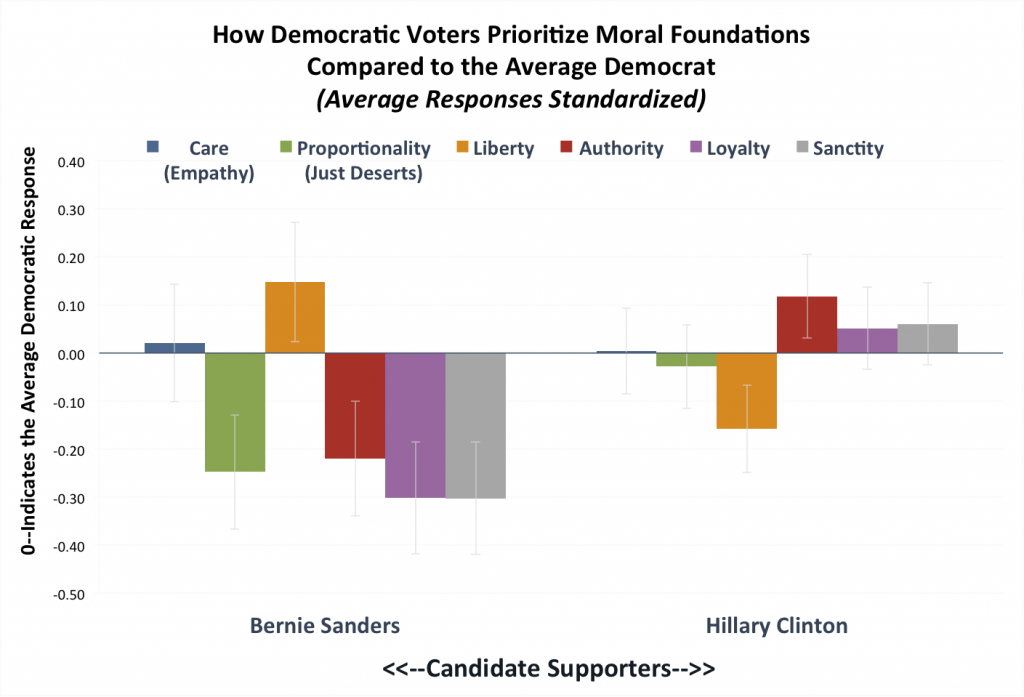

2) An expanded analysis of the Democratic race

The analyses we presented in our Vox essay examined each candidate’s supporters compared to the average American. But these candidates are competing to win over their respective parties’ median voters in the primaries and caucuses. So in this post we zoom in on each party separately. How do each candidate’s supporters compare to the average Republican or average Democrat?

Here we re-standardized each foundation scale among just Democrats. Thus each foundation scale has a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1, in which 0 represents the average Democrat in our sample. Then for each Democratic candidate’s supporters, we graphed the average standardized response for each of the six moral foundations.

In Figure 1-D below we show how each Democratic candidate’s supporters prioritize the moral foundations compared to the average Democrat. This means that bars above (or below) zero indicate that Sanders or Clinton supporters place more (or less) emphasis on that moral foundation compared to the average Democrat. Here we break out the Authority, Loyalty, and Sanctity foundations separately to get a more granular picture.

Figure 1-D

Note: This chart reports standardized responses (z-scores), which show how each candidates’ supporters responded to questions about each moral foundation compared to the average Democrat. Y-axis is in standard deviations from the mean. Error bars show 95 percent confidence intervals around the means.

Supporters of Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders do not differ on the Care foundation. Both candidates are progressives who prioritize concerns over those who are suffering. Beyond that Sanders and Clinton supporters diverge.

Sanders draws those with a more libertarian profile, prioritizing concerns about personal freedom and eschewing the socially conservative foundations. Clinton supporters tend to draw from a (relatively speaking) more conservative profile. In some ways, 2016 looks a lot like 2008. Political scientists Marc Hetherington and Jonathan Weiler found that while Clinton and Obama’s voting records were essentially “ideologically indistinguishable,” Clinton managed to attract more authoritarian-leaning Democrats while Obama attracted liberals concerned with individual autonomy. In both the 2008 and 2016 campaigns, Clinton has exuded an image of toughness, often characterizing herself as a “fighter.” She voted for the Iraq War in 2003, has supported greater US involvement fighting ISIS and training Syrian rebels, and keeping troops in Afghanistan, while Sanders opposed the war and these interventions. In fact, Terry Michael writing for the libertarian Reason magazine even declared that compared to Hillary Clinton, “Sanders looks downright Ayn Rand-ish.”

Sanders supporters also stands apart from Clinton’s supporters (and libertarians), in rating proportionality much less relevant to their moral judgments. This aligns with Sanders’ proposing greater expansions of government social welfare programs and higher taxes on the wealthy in comparison to Clinton.

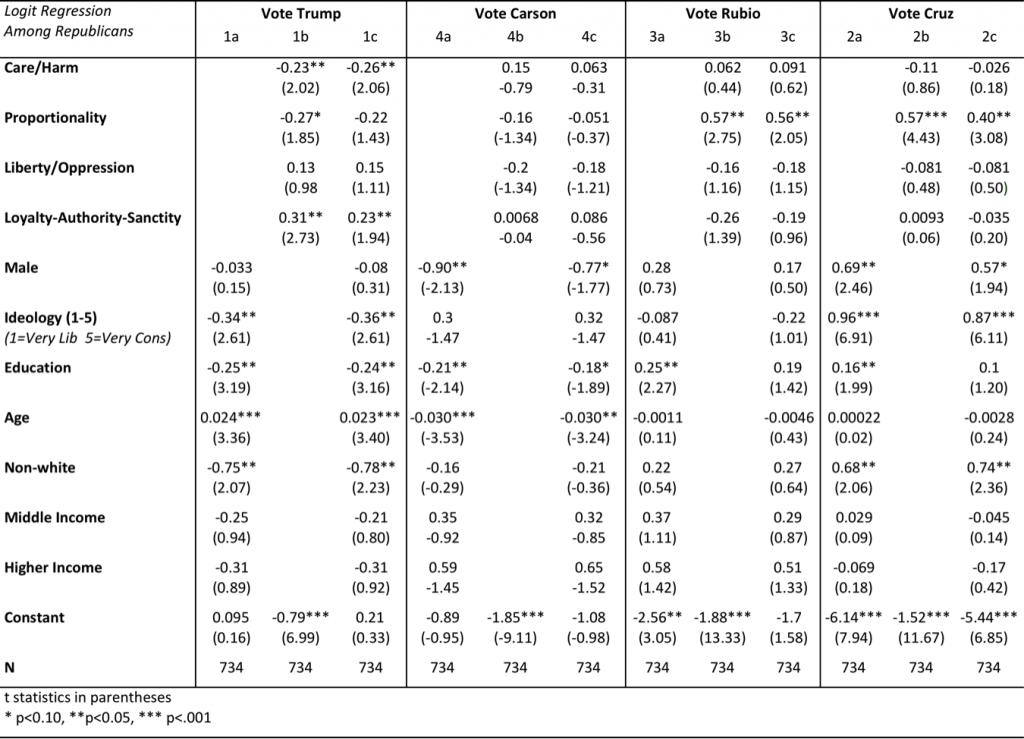

3) An expanded analysis of the Republican race

Next we turn to the top four vote getters in the Republican primaries: Donald Trump, Ted Cruz, Marco Rubio, and Ben Carson. How do their supporters compare with the average Republican voter?

To examine this, we re-standardized each foundation scale among just Republicans. Thus each foundation scale has a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1, in which 0 represents the average Republican in our sample. Then for each Republican candidate’s supporters, we graphed the average standardized response for each of the six moral foundations.

In Figure 1-R below we show how each Republican candidate’s supporters prioritize each of the moral foundations compared to the average Republican. This means that bars above (or below) zero indicate the candidate’s supporters place more (or less) emphasis on that moral foundation compared to the average Republican. Here we also break out the Authority, Loyalty, and Sanctity foundations.

Figure 1-R

Note: This chart reports standardized responses (z-scores), which show how each candidates’ supporters responded to questions about each moral foundation compared to the average Republican. Y-axis is in standard deviations from the mean. Error bars show 95 percent confidence intervals around the means.

Notably, the two candidates catapulted to public office by the tea party movement—Marco Rubio and Ted Cruz—stand out because of their supporters’ high endorsement of proportionality. These candidates have drawn in the fiscally conservative wing of the GOP that wants people to be rewarded in prorportion of their achievements, and punished in proportion to their failings. Both sets of supporters also score relatively low on on the Care foundation. When it comes to government adjudicating between justice and mercy, these voters opt for justice. This may be why David Brooks has called Cruz “brutal” while Rush Limbaugh described him as principled and consistent.

These results also highlight the rift between Rubio and the remaining top contenders. Rubio draws the more secular or centrist supporters (indicated by lower purple and grey bars on Loyalty and Sanctity) while Cruz, and Trump attract more religious and culturally conservative supporters. While both Cruz and Rubio have heavily courted key evangelicals for endorsements, Cruz has taken the lead, as some religious leaders express skepticism of Rubio’s financial backers who support gay rights.

These moral differences among supporters also map onto to policy differences of the candidates: For instance, Marco Rubio has sought to liberalize immigration rules while Ted Cruz has promised to oppose a pathway to citizenship for unauthorized immigrants “today, tomorrow, forever” and Donald Trump has gone even further promising to deport every undocumented immigrant.

Ben Carson stands out as the candidate with more empathetic voters, those who score higher on the Care foundation. This may reflect Carson’s warmer style and refusal to engage his opponents in what he calls the “politics of personal destruction.”

One of the biggest surprises in our dataset was that Donald Trump’s supporters did not appear particularly unusual. Part of this is due to the fact that his higher vote share means his supporters are closer to average. However, his supporters do significantly deviate from the average Republican voter in placing greater weight on the Authority/Loyalty/Sanctity composite variable.

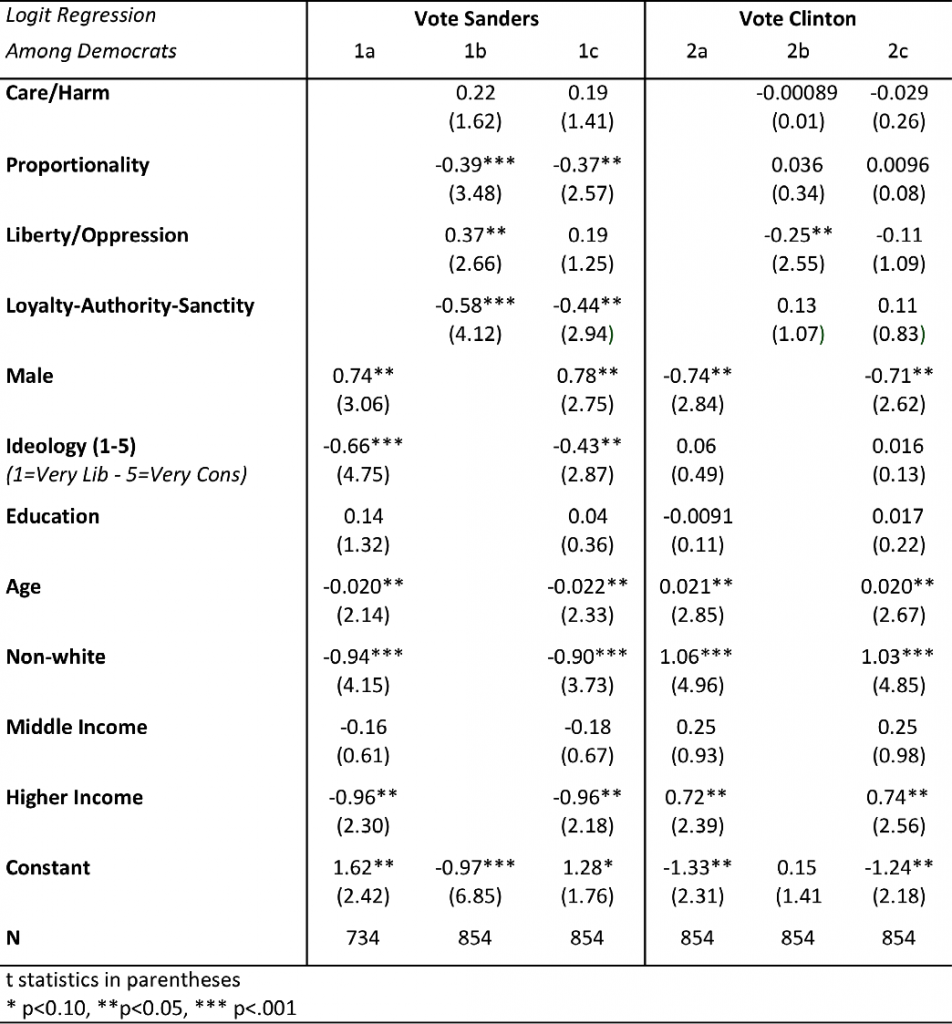

4) Details about our LOGIT regressions

To find out if moral foundations improves predicting vote choice we performed a series of regression analyses, one for each presidential candidate. We carried out Logit regressions separately for the Democratic candidates among Democratic respondents, and Republican candidates among Republican respondents.

In order to see if adding the moral foundations improved prediction above and beyond the demographic factors that are usually used, we ran three different models per candidate:

- Model 1 (Column A): This model examines how well self-reported ideology (liberal to conservative) and the standard set of demographic variables predict vote choice.

- Model 2: (Column B): This model examines how well each moral foundation[2] predicts voting for each candidate, while controlling for the effects of the other moral foundations, but without accounting for the effects of demographics and self-reported ideology.

- Model 3: (Column C): This model combines Model 1 and 2 to examine how well each moral foundation predicts vote choice, while also accounting for the effects of demographics, self-described ideology, as well as the other moral foundations.

First we report results that predict voting for a Democratic candidate among Democrats in Table 1-D:

Democratic Primary

Table 1-D

Note: Logit regression conducted among Democrats only, results report standardized betas, t statistics in parentheses, clustered standard errors by state.

Before controlling for demographic factors, the Liberty foundation significantly predicts a vote for Sanders and a vote against Clinton among Democrats. However, young white civil libertarians seem to largely be driving this effect. Once age and race are included in the analysis, the Liberty foundation no longer predicts voting for Bernie Sanders. When accounting for demographics, Sanders is negatively predicted by Proportionality and Authority/Loyalty/Sanctity. The moral foundations do not significantly predict a vote for Hillary Clinton, after controlling for background and ideology among Democrats.

Second we report results that predict voting for a Republican candidate among Republicans. We first present logit regression results for the top four Republican vote getters shown in Table 1-R(a). Candidates are ordered from left to right according to their respondents’ average reported ideology.

Republican Primary

Table 1-R(a)

Note: Logit regression conducted among Republicans only, results report standardized betas, t statistics in parentheses, clustered standard errors by state.

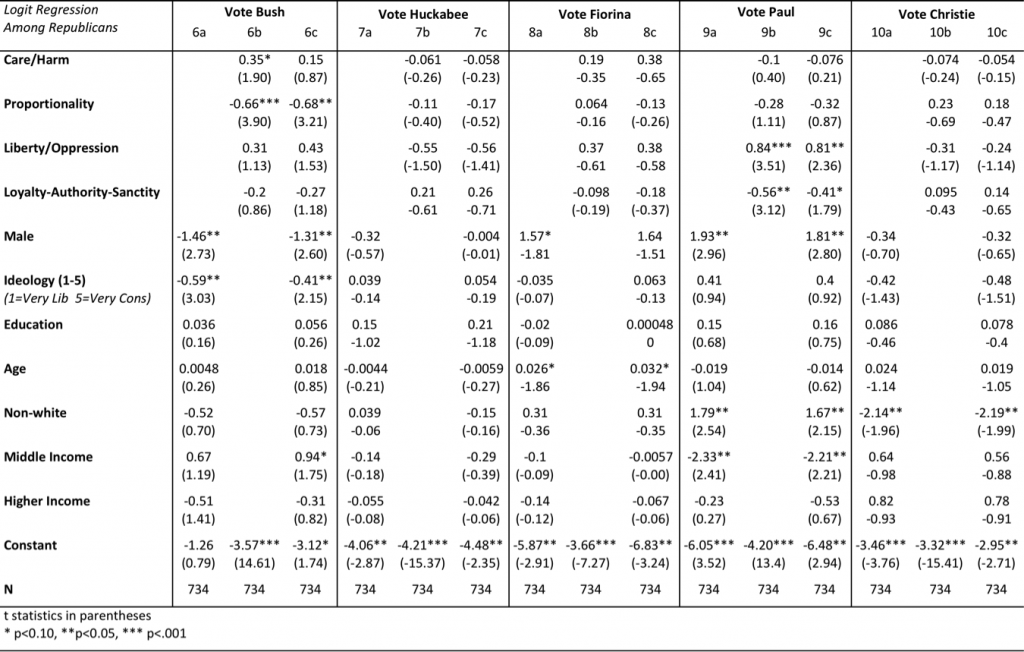

Next we present logit regression results for the remaining Republican candidates shown in Table 1-R(b). Candidates are ordered from left to right according to their respondents’ average reported ideology.

Table 1-R(b)

Note: Logit regression conducted among Republicans only, results report standardized betas, t statistics in parentheses, clustered standard errors by state.

Among Republicans, the moral foundations significantly predicted vote choice for Donald Trump, Ted Cruz, Marco Rubio, Jeb Bush, and Rand Paul, but not for Mike Huckabee, Ben Carson, Carly Fiorina, or Chris Christie.

We find the Authority/Loyalty/Sanctity foundation is significantly predictive of voting for Donald Trump, but none of the other GOP candidates. The Care foundation significantly predicts voting against Trump. This pattern is consistent with claims that Trump attracts authoritarians. Proportionality significantly predicts support for Cruz and Rubio even when controlling for ideology and demographics. These candidates draw the fiscal conservatives who want society to reward people according to what they have earned, not according to their needs. However, in contrast to Cruz and Rubio, Proportionality predicts voting against Jeb Bush. Instead Bush attracts Republicans who are less focused on enforcing proportional fairness in society. High ratings on the Liberty foundation significantly predict a vote for Rand Paul while the Authority/Loyalty/Sanctity foundation negatively predicts it. Rand Paul draws the libertarian vote but has projected a rather narrow moral appeal.

4) Responses to any questions that come up in response to the Vox essay.

[We will post responses here as questions or criticisms arise. Please send questions to eekins at cato.org]

Updated 4/6/2016: Response to commenter Betsy: Because Trump has a larger share of the vote, his supporters’ standardized scores for each moral foundation are more likely to be closer to average. Since 0 indicates the median voter, candidates with larger vote shares will appear closer to average. However, Jeb Bush who had only about 4% of the vote also had supporters who are close to the national average. Table 1-R(a) shows that Trump is the only Republican candidate significantly positively predicted in a multivariate regression by the Loyalty-Authority-Sanctity foundation and negatively predicted by the Care/Harm foundation. While not all Trump supporters fit the profile of a voter who scores low on compassion and high on respect for authority, a considerable share do. Another method to investigate your question is to conduct cluster analyses of Trump supporters. We have done some preliminary tests finding roughly 2-3 groups. One group scores particularly high on Loyalty-Authority-Sanctity, while another group appears to be less engaged and scores lower on all the foundations. When these different groups are averaged together, the average Trump supporter is closer to the average.

Regarding model fit, Wald Tests reveal that adding moral foundation variables often does significantly improve model fit. For instance for Bernie Sanders Wald=17.70 p < .001, or for Donald Trump Wald=11.14 p <.05, for Ted Cruz Wald=14.01 p < .01. However, it does not for Hillary Clinton. As we have shown, for several candidates the moral foundations were significantly predictive of vote choice. Table 1-D should address the logit model you suggest. This regression is run among Democratic voters only and predicts voting for Sanders or Clinton respectively among Democratic voters.

Footnotes

[1] The survey included oversamples of African-Americans, Hispanics, and Tea Party supporters. We apply weights throughout our analyses.

[2] Since Authority, Loyalty, and Sanctity are moderately intercorrelated, we included the composite variable in the regression.

Read More