Liberals are WEIRDer than Conservatives

Guest post by Thomas Talhelm (on a recent publication with Haidt, mentioned by Tom Edsall in NYT)

A few years ago, psychologists looked at all of the psychological studies of people in different cultures and concluded that Westerners are WEIRD. That’s an acronym, not an insult. People from Western Educated Industrialized Rich Democratic countries are consistent psychological outliers compared to the other 85% of the world’s population.

On psychological tests, Westerners tend to view scenes, explain behavior, and categorize objects analytically. But the vast majority of people around the world more often think intuitively—what psychologists call “holistic thought.”

Five years ago, I had just arrived at the University of Virginia, and I had a thought flash: Aren’t most of these WEIRD elements even more true of liberal culture within the United States? Liberalism thrives in universities (Education), cities (Industrialized), the wealthy East and West coasts (Rich), and ultra-pluralistic groups like Occupy Wall Street and Unitarian churches (Democratic). So if Westerners think WEIRDly, maybe liberals think even WEIRDer. I went to talk with my advisors, Shige Oishi and Jonathan Haidt, and they liked the idea and joined me on the project (along with Xuemin Zhang, Felicity Miao, and Shimin Chen)

Five years and thousands of participants later, we just published the findings in Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. We found that American liberals think even WEIRDer, even more unlike the rest of the world, than the average American conservative.

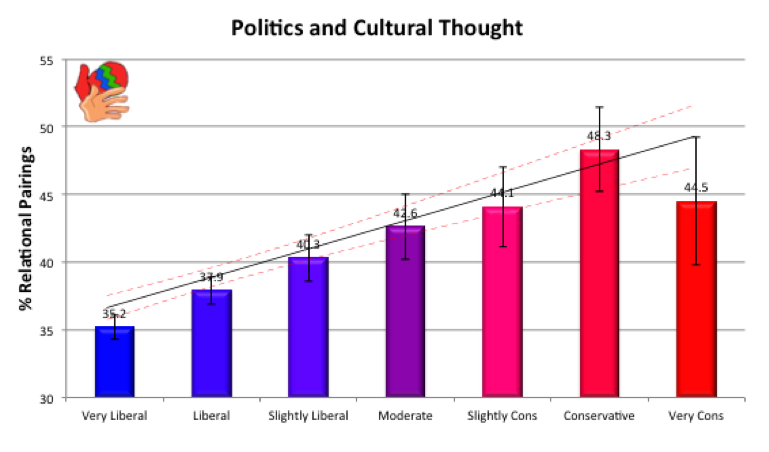

We studied this using tests that cultural psychologist use to measure cognitive differences. In one test, participants have to choose two of three items to categorize together, such as scarf, mitten, and hand. Westerners tend to categorize scarf and mitten because they belong to the same abstract category. People in most other cultures tested such as China and the Middle East tend to pair mitten and hand because those two things have a relationship with each other. American liberals (on the left side of the graph below) choose those relational pairing much less frequently. American conservatives (on the right side) are more likely than liberals to do the relational pairing. It’s not a majority, but we can still see that the conservatives are less WEIRD in their judgments than are liberals.

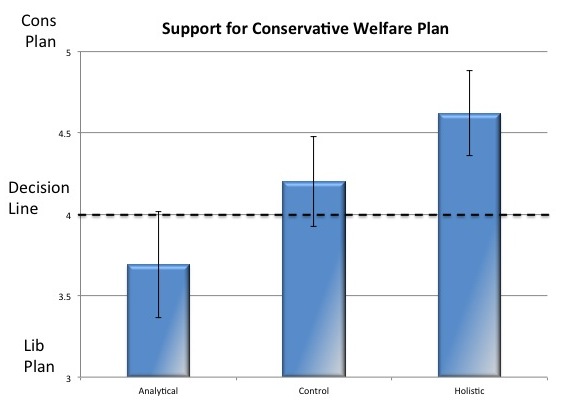

Next we wondered if temporarily changing people’s thought style would change their political opinions, so we asked participants to think analytically—even if that was the opposite of their own style. Then participants read articles about social issues like welfare and drug sentencing. The temporary analytic shift made people more likely to support the liberal side, and a temporary intuitive shift made them more likely to support the conservative side.

This all leads me to think that it’s no accident that people call American politics a “culture war.” Liberals and conservatives do really see the world as if they were from different cultures, and it influences whether they see welfare recipients as moochers dragging down hard-working Americans or as people in need of a helping hand. It influences whether we see rehabilitation for drug offenders as rewarding bad behavior or as treating an illness. Social policies have facts and data, but how people see those policies depends a great deal on their cultural mindset.

Read MoreCountry of ambition and pollution

I’m traveling in Asia for three months to do research for my next book, Three Stories About Capitalism. Each Westerner gets just one chance to have first impressions of China, and mine lived up to my hopes for memorability.

To prepare for the trip, I’ve been reading Evan Osnos’ much-talked-about book Age of Ambition. It’s about how China is changing as the market-oriented reforms initiated by Deng Xioping in 1979 have led to such rapidly rising prosperity–and ambition for far more prosperity–since the 1990s. Osnos opens the book by describing the “fever” of aspiration that was sweeping the big cities when he first arrived in 2005. It was the “belief in the sheer possibility to remake a life,” by rapid success in business. These new possibilities are changing everything, including dating. We learn about a dating show in which a young woman brushes off an appeal from a suitor who talks about taking her out on his bicycle. The woman says “I’d rather cry in a BMW than smile on a bicycle.”

So I was well prepared to encounter a country abuzz with energy, entrepreneurialism, and materialism, with little trace of communism. But I didn’t expect the evidence to hit me as soon as I boarded the China Southern flight in Kuala Lumpur, to fly via Guangzhou to Shanghai:

1) When I sat down in my seat, the seat protector in front of my face had an advertisement for marble tiles, because the sort of person who can take a plane is probably also renovating his home or apartment in a lavish Western style (as their website makes clear).

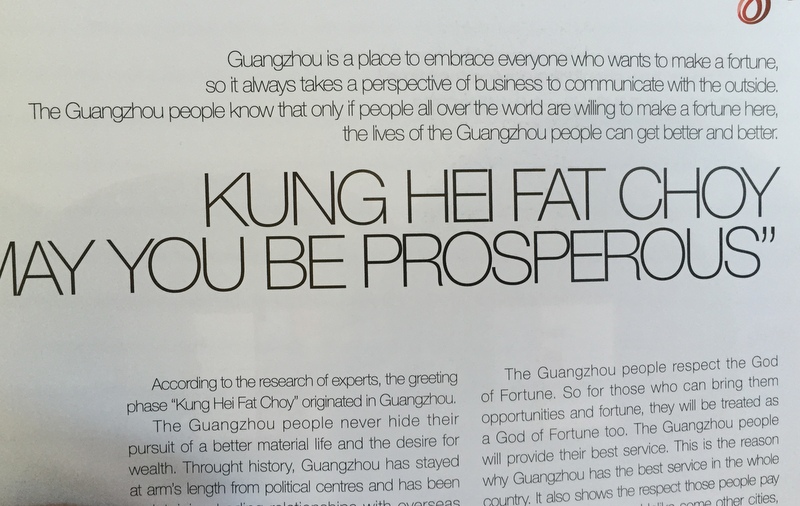

2) The in flight magazine had the article below, informing flyers that “Guangzhou is a place to embrace everyone who wants to make a fortune.”

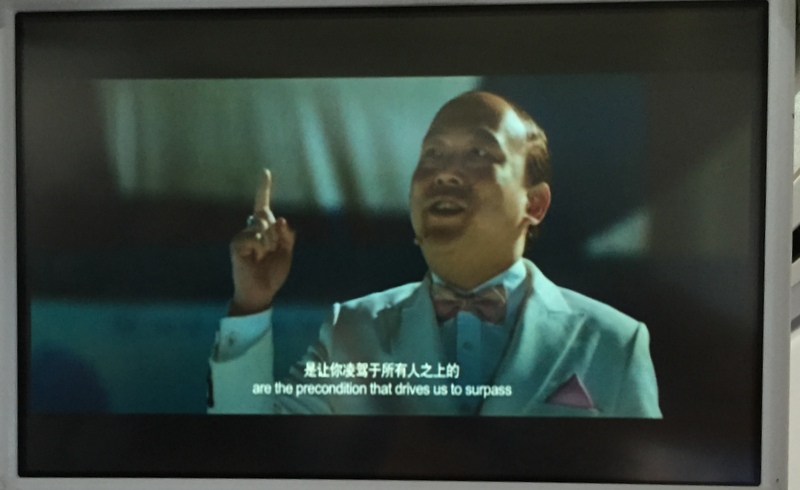

3) The movie playing during the flight was “Fen shou da shi” (The Breakup Guru), a comedy that included a prosperity guru preaching to a stadium full of upward strivers. In the scene below he says: “our biggest dreams are the precondition that drives us to surpass….” something or other. It was a secular Chinese version of the prosperity gospel preachers we have in the USA. (Granted, the movie was making fun of this guy, but his type is recognizable to Chinese movie-goers).

4) At one point during the flight I checked my watch and saw that my seat-mate, an 18 year old Chinese college student, was looking at my watch. I assumed he wanted to know the time so I turned the watch toward him. He said “Omega. I recognize that mark.” I’ve worn this watch for 18 years and nobody has ever commented on it in America or Europe.

These are all small things, but it was notable that as I was reading Osnos on the plane, all I had to do was raise my head and look around to find four pieces of evidence that (a part of) Chinese society is consumed by the material ambition Osnos describes.

The next surprise was the air pollution. We’ve all heard so much about the awful air quality in Chinese cities, but I was still stunned by my first encounter upon landing in Guangzhou, an industrial city near Hong Kong. It was a sunny day, and when I looked straight up I could see a blue sky, photographed here through an airport window:

Yet when you look horizontally, through the haze, it looks like a foggy day, or a day with light snow:

The smog is so bad that you can actually see it in the cavernous spaces of the airport. Signs far away look a bit blurry. It looks and smells like you are walking around in a heavily trafficked underground parking garage.

The air quality in Shanghai feels slightly better, but is still far worse than anything I’ve seen in my life. But I will say this about the smog: it makes night scenes more dramatic:

Despite the pollution, the city is beautiful and fascinating. It feels very safe, the food is delicious, and I am looking forward to my three weeks here, based at NYU’s brand new campus.

Read More

Two stories about capitalism, which explain why economists don’t reach agreement

Why is it that if you know an economist’s political leaning you can guess many of his or her factual beliefs? Would raising the minimum wage would help or hurt the poor overall? Is austerity or stimulus is the more reliable route to economic recovery? Is rising income inequality a drag on growth? Is Piketty’s data sound? These are factual questions, not value judgments, so why don’t economists converge? It’s the same for historians. If you know which party they vote for, you can guess their general views on capitalism, and on the recent debates about whether slavery in the American South was crucial for its development (by providing cotton for the mills in Manchester), or irrelevant for the spectacular flowering of capitalism in the 19th century.

The answer, in part, is that there are two basic master narratives about capitalism that have been circulating in the West since the time of Adam Smith. One story is that capitalism (and business more generally) is exploitation, so we need a strong government to keep the greed and amorality of capitalists in check. The other story is that capitalism is liberation. People were mostly serfs and peasants until capitalism came along and freed people to keep the fruits of their own labor, so we need to keep government’s role to a minimum, given how prone it is to capture, corruption, and inefficiency. Let the markets work in peace.

I’ve been seeing these stories all around me since 2011, when I moved to a business school at the same time that the Occupy Wall Street protests broke out. I find it so helpful to know these stories that I turned them into 70 second video montages to share them with others. The two montages are included in a talk I gave in November at the Zurich Minds festival, which you can watch below.

The talk explains the most useful concept I have encountered in recent years – the concept of “wicked problems,” which refers to problems that activate the moral and political identities and desires of the experts, thereby warping their thinking.

Wicked problems (like poverty, education, or racial inequality) activate all the post-hoc reasoning and biased searching for support that I described in chapters 3 and 4 of The Righteous Mind. They are so different from tame problems (like curing cholera), which can be very challenging technically, but they just sit there and let the experts converge upon solutions. My hope is that a better understanding of moral psychology can help people to think clearly about economic debates, which are usually also wicked problems with moral implications.

I have also made the two montages available as separate files, in the hope that teachers and professors will find them useful for showing in classes that discuss morality, history, politics, or economics.

You can also download the two separate stories at: www.ethicalsystems.org/capitalism

Read More