Bring the Cultural Revolution to America!

No, I don’t mean that we should have shame circles and ruinous economic policies. I mean that I hope someone will find a way to bring the extraordinary collection of the Shanghai Propaganda Poster Art Center to America in time for the 50th anniversary of the cultural revolution, this June. I spent four months traveling across Asia last year, and one of the high points was my visit to this small museum, tucked away in the basement of an apartment building in Shanghai’s Former French Concession neighborhood.

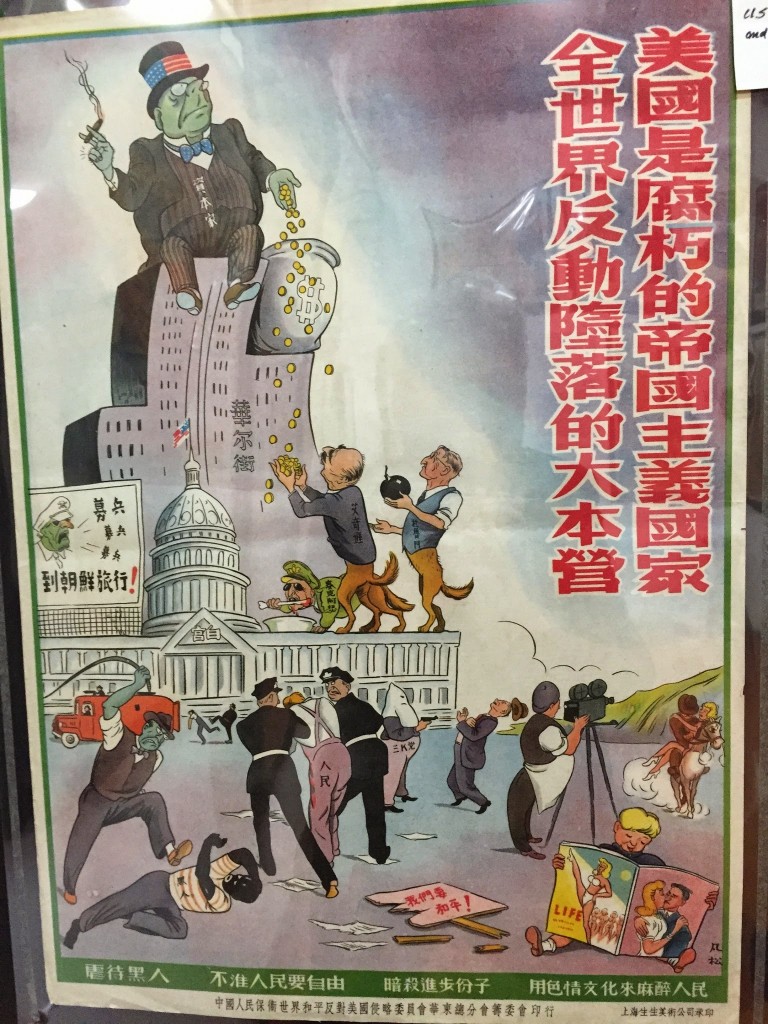

I was in China to do research for my next book, on capitalism and morality, and wanted to learn how China made the transition from demonizing capitalism to embracing it. Just look at this poster from 1951 – it’s a “super-stimulus” for all the bad things ever said about capitalism. The caption reads: “America is a rotten imperialist country, and the camp of such people around the world.” The fat banker drops money down to the “running dogs” of American imperialism — President Truman (holding The Bomb), Dean Acheson, and Douglas MacArthur.

Anti-capitalism, 1952. Photo by Jon Haidt, with permission of Shanghai Propaganda Poster Arts Center

At the bottom of the scene.. well, the racism, violence, and moral degradation that are thought to flow inevitably from capitalism could not be clearer.

At the PPAC, you can follow the evolution of Chinese history, economics, and aesthetics, from the “Shanghai girl” posters of the 1930s through the early post-revolutionary optimism, the cold war, and the madness of the cultural revolution, in which young people were urged to band together to destroy large parts of China’s cultural and philosophical heritage, to make way for a fresh start, as in the poster below:

You can feel the calmness return after the death of Mao, when Deng Xiaoping allows the first sprouts of economic freedom, and prosperity begins to rise. Contrast the anti-capitalist poster above with this poster from 1982, which in a sense is just a return to the ancient Chinese value of prosperity. The caption reads “getting better each year.” Boy was that prophetic.

“Getting better each year. Photo by Jon Haidt, of poster from Shanghai Propaganda Poster Arts Center

During my visit, I struck up a conversation with the quiet, gentle proprietor and owner of the collection, Mr. Yang Pei Ming. He was born in 1945, in the desperate last months of the Japanese occupation. His father was murdered in an early wave of anti-capitalist fervor in the early 1950s. Yang lived through the famine of 1960 and was in college in 1966 when the cultural revolution broke out, first among college students in Beijing. He was sent to the countryside and never finished college. (You can read a profile of Mr. Yang here).

He began collecting propaganda posters on a whim in 1995 and he now has what appears to be the world’s largest collection of such posters. It is his personal collection, part of which he puts on display in a few basement rooms of an ordinary apartment building. The rooms are barely heated — the museum earns so little money from admission fees that he can’t afford to pay for heat (hence the parka in the photo above). The “museum” is not climate controlled, and the posters will decay over time from fluctuations in temperature and humidity.

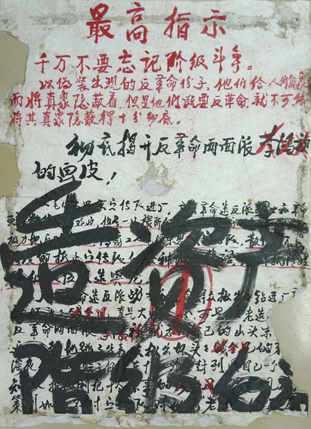

And this is why I hope that we can “bring the cultural revolution to America.” I hope somebody reading this post knows somebody who is connected to an art museum. Mr. Yang needs help to preserve the best parts of his collection. I’m hoping that the curator of an art museum will take an interest, visit the collection, and work with Mr. Yang to bring the best pieces to America or Europe. He has done several shows before. But he needs much more financial support, and 2016 would be the perfect time for a major show. It’s the 50th anniversary of the cultural revolution, and interest in China and Chinese history has never been higher in the West. In particular, there has never been an exhibit outside China of the Dazibao — the giant calligraphed political statements and street art that were put up by students in Beijing, which launched the cultural revolution in 1966. Mr. Yang has preserved many of the originals of these fragile artifacts:

Dazibao (Big Character Posters). The large black characters say: “Thoroughly expose the reactionary crimes of Li Hongzhen!” From the collection of the Shanghai Propaganda Poster Arts Center

You can learn more about the PPAC at it’s home page, or in this recent article at US News.

If you are interested in supporting Mr. Yang, or bringing his collection to an art museum, please contact him directly: pmyang999 [at] 163.com or else contact me: haidt [at] nyu.edu

Read More

Country of ambition and pollution

I’m traveling in Asia for three months to do research for my next book, Three Stories About Capitalism. Each Westerner gets just one chance to have first impressions of China, and mine lived up to my hopes for memorability.

To prepare for the trip, I’ve been reading Evan Osnos’ much-talked-about book Age of Ambition. It’s about how China is changing as the market-oriented reforms initiated by Deng Xioping in 1979 have led to such rapidly rising prosperity–and ambition for far more prosperity–since the 1990s. Osnos opens the book by describing the “fever” of aspiration that was sweeping the big cities when he first arrived in 2005. It was the “belief in the sheer possibility to remake a life,” by rapid success in business. These new possibilities are changing everything, including dating. We learn about a dating show in which a young woman brushes off an appeal from a suitor who talks about taking her out on his bicycle. The woman says “I’d rather cry in a BMW than smile on a bicycle.”

So I was well prepared to encounter a country abuzz with energy, entrepreneurialism, and materialism, with little trace of communism. But I didn’t expect the evidence to hit me as soon as I boarded the China Southern flight in Kuala Lumpur, to fly via Guangzhou to Shanghai:

1) When I sat down in my seat, the seat protector in front of my face had an advertisement for marble tiles, because the sort of person who can take a plane is probably also renovating his home or apartment in a lavish Western style (as their website makes clear).

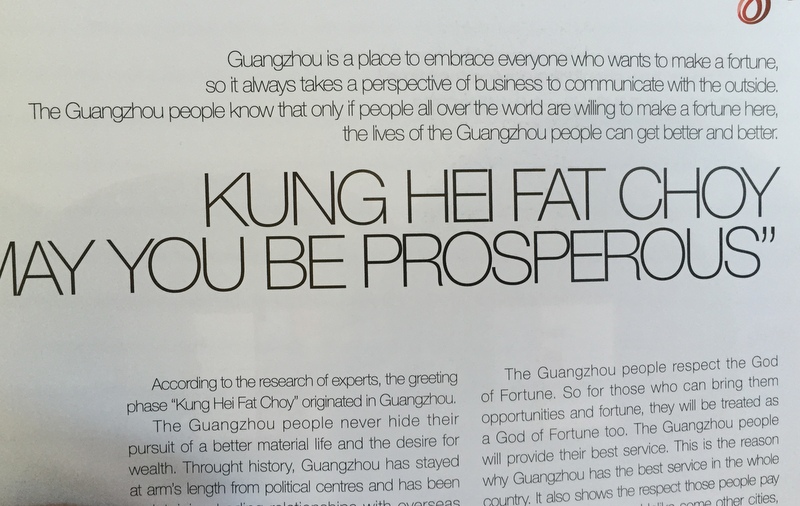

2) The in flight magazine had the article below, informing flyers that “Guangzhou is a place to embrace everyone who wants to make a fortune.”

3) The movie playing during the flight was “Fen shou da shi” (The Breakup Guru), a comedy that included a prosperity guru preaching to a stadium full of upward strivers. In the scene below he says: “our biggest dreams are the precondition that drives us to surpass….” something or other. It was a secular Chinese version of the prosperity gospel preachers we have in the USA. (Granted, the movie was making fun of this guy, but his type is recognizable to Chinese movie-goers).

4) At one point during the flight I checked my watch and saw that my seat-mate, an 18 year old Chinese college student, was looking at my watch. I assumed he wanted to know the time so I turned the watch toward him. He said “Omega. I recognize that mark.” I’ve worn this watch for 18 years and nobody has ever commented on it in America or Europe.

These are all small things, but it was notable that as I was reading Osnos on the plane, all I had to do was raise my head and look around to find four pieces of evidence that (a part of) Chinese society is consumed by the material ambition Osnos describes.

The next surprise was the air pollution. We’ve all heard so much about the awful air quality in Chinese cities, but I was still stunned by my first encounter upon landing in Guangzhou, an industrial city near Hong Kong. It was a sunny day, and when I looked straight up I could see a blue sky, photographed here through an airport window:

Yet when you look horizontally, through the haze, it looks like a foggy day, or a day with light snow:

The smog is so bad that you can actually see it in the cavernous spaces of the airport. Signs far away look a bit blurry. It looks and smells like you are walking around in a heavily trafficked underground parking garage.

The air quality in Shanghai feels slightly better, but is still far worse than anything I’ve seen in my life. But I will say this about the smog: it makes night scenes more dramatic:

Despite the pollution, the city is beautiful and fascinating. It feels very safe, the food is delicious, and I am looking forward to my three weeks here, based at NYU’s brand new campus.

Read More