Bring the Cultural Revolution to America!

No, I don’t mean that we should have shame circles and ruinous economic policies. I mean that I hope someone will find a way to bring the extraordinary collection of the Shanghai Propaganda Poster Art Center to America in time for the 50th anniversary of the cultural revolution, this June. I spent four months traveling across Asia last year, and one of the high points was my visit to this small museum, tucked away in the basement of an apartment building in Shanghai’s Former French Concession neighborhood.

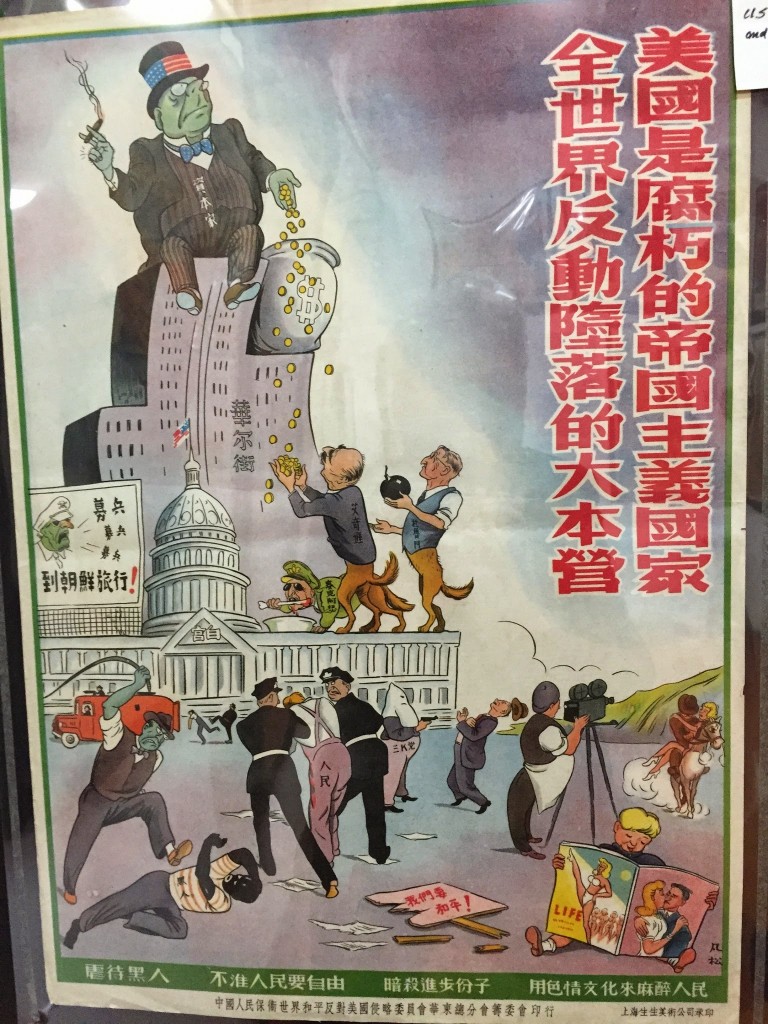

I was in China to do research for my next book, on capitalism and morality, and wanted to learn how China made the transition from demonizing capitalism to embracing it. Just look at this poster from 1951 – it’s a “super-stimulus” for all the bad things ever said about capitalism. The caption reads: “America is a rotten imperialist country, and the camp of such people around the world.” The fat banker drops money down to the “running dogs” of American imperialism — President Truman (holding The Bomb), Dean Acheson, and Douglas MacArthur.

Anti-capitalism, 1952. Photo by Jon Haidt, with permission of Shanghai Propaganda Poster Arts Center

At the bottom of the scene.. well, the racism, violence, and moral degradation that are thought to flow inevitably from capitalism could not be clearer.

At the PPAC, you can follow the evolution of Chinese history, economics, and aesthetics, from the “Shanghai girl” posters of the 1930s through the early post-revolutionary optimism, the cold war, and the madness of the cultural revolution, in which young people were urged to band together to destroy large parts of China’s cultural and philosophical heritage, to make way for a fresh start, as in the poster below:

You can feel the calmness return after the death of Mao, when Deng Xiaoping allows the first sprouts of economic freedom, and prosperity begins to rise. Contrast the anti-capitalist poster above with this poster from 1982, which in a sense is just a return to the ancient Chinese value of prosperity. The caption reads “getting better each year.” Boy was that prophetic.

“Getting better each year. Photo by Jon Haidt, of poster from Shanghai Propaganda Poster Arts Center

During my visit, I struck up a conversation with the quiet, gentle proprietor and owner of the collection, Mr. Yang Pei Ming. He was born in 1945, in the desperate last months of the Japanese occupation. His father was murdered in an early wave of anti-capitalist fervor in the early 1950s. Yang lived through the famine of 1960 and was in college in 1966 when the cultural revolution broke out, first among college students in Beijing. He was sent to the countryside and never finished college. (You can read a profile of Mr. Yang here).

He began collecting propaganda posters on a whim in 1995 and he now has what appears to be the world’s largest collection of such posters. It is his personal collection, part of which he puts on display in a few basement rooms of an ordinary apartment building. The rooms are barely heated — the museum earns so little money from admission fees that he can’t afford to pay for heat (hence the parka in the photo above). The “museum” is not climate controlled, and the posters will decay over time from fluctuations in temperature and humidity.

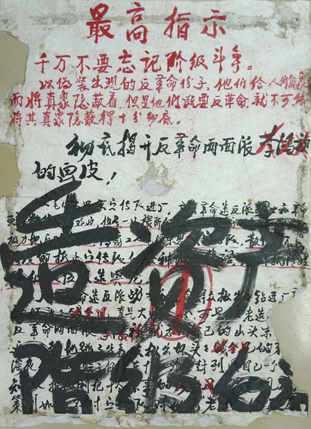

And this is why I hope that we can “bring the cultural revolution to America.” I hope somebody reading this post knows somebody who is connected to an art museum. Mr. Yang needs help to preserve the best parts of his collection. I’m hoping that the curator of an art museum will take an interest, visit the collection, and work with Mr. Yang to bring the best pieces to America or Europe. He has done several shows before. But he needs much more financial support, and 2016 would be the perfect time for a major show. It’s the 50th anniversary of the cultural revolution, and interest in China and Chinese history has never been higher in the West. In particular, there has never been an exhibit outside China of the Dazibao — the giant calligraphed political statements and street art that were put up by students in Beijing, which launched the cultural revolution in 1966. Mr. Yang has preserved many of the originals of these fragile artifacts:

Dazibao (Big Character Posters). The large black characters say: “Thoroughly expose the reactionary crimes of Li Hongzhen!” From the collection of the Shanghai Propaganda Poster Arts Center

You can learn more about the PPAC at it’s home page, or in this recent article at US News.

If you are interested in supporting Mr. Yang, or bringing his collection to an art museum, please contact him directly: pmyang999 [at] 163.com or else contact me: haidt [at] nyu.edu

Revolutions go a bit like this: Revolutionary movement first harnessess realistic or unrealistic / real or imagined hopes, wishes, dreams, wants, needs, deficiencies, problems, injustices, etc. If the revolution succeeds, it releases hatreds, greed, hunger for power, genuine enthusiasm, cacophony of demands and wishes, feverish changes and renewals, etc. As overwhelming majority of possible arbitrary political changes have negative effects, and the “rationality” of revolution doesnt impove this ratio much, soon the negative effects of revolutionary change become dominant and apparent despite some possible good changes. At the same time oppression, violence, disorder, mass murders, internal war, etc. may take their toll. As the time goes by people and elites become more exhausted, tired and angry (perhaps internally, because open opposition is not allowed), and they are ready to grab opportunities and leaders, which provide security, order, more predictable future, more conservative and time tested policies, restoration of what was before, etc. This process is never a return to exactly what was before, the full blown revolution leaves almost always at least some changes to the society. Changes can be anything from fairly insignificant to seeds of profound changes in the future.

As we live in societies where e.g. constant and unlimited changes to one direction are adored in the form of “progress”, and “Change” without qualifiers is used as a positive and uplifting election slogan, most people, including elites, are not fully able to assess what is good change and what is not. After all, if meteorite swoops through your house and destroys it, it is change too.