Trigger Warnings Cause Non Sequiturs

Below is the letter to the editor that Greg Lukianoff and I submitted to the New York Times in response to an op-ed by Cornell philosophy professor Kate Manne, which defended the use of trigger warnings.

The Times did not respond to our submission, so here it is:

To the Editor:

Re: “Why I use trigger warnings” (Opinion, Sept. 19): Kate Manne’s efforts to alert her philosophy students about potentially upsetting course content shows her to be a caring teacher. But her critique of our essay condemning trigger warnings begins with a non sequitur. She is surely right that “the evidence suggests” that some of her students “are likely to have suffered some sort of trauma.” But that does not logically imply that “the benefits of trigger warnings can be significant.” We have not found any empirical evidence that trigger warnings yield any psychological benefits, whereas there is empirical evidence suggesting that they might be harmful. So it is more logical to conclude that if trauma is common, then the harms caused by trigger warnings might be significant.

Manne then offers an analogy: “Exposing students to triggering material without warning seems more akin to occasionally throwing a spider at an arachnophobe.” This is not a valid analogy. Asking students to read novels or Greek myths that include sexual assault is like saying the word spider in the presence of an arachnophobe, which anxiety experts tell us is a good way to reduce the long-term emotional power of spiders. If well-meaning teachers and friends work together to help an arachnophobe avoid exposure to the word spider, or to pictures of spiders, spider webs, and Spiderman, they will strengthen the arachnophobe’s conviction that mere reminders of spiders are dangerous. This is how a temporary and reversible phobia can be hardened into a lifelong and debilitating identity.

Manne also asserts that “there seems to be very little reason not to give these warnings.” It’s simple courtesy, no? Trigger warnings are like “advisory notices given before films and TV shows.” But those warnings are given so that parents can keep their children safe from material for which they are not yet emotionally mature enough. This is why the American Association of University Professors has condemned the use of trigger warnings as being “at once infantilizing and anti-intellectual.”

Furthermore, once a few professors start giving these warnings, students will begin to request them from their other professors, and this may lead to a cascade of caution among the rest of the faculty. Last year, seven humanities professors from seven colleges penned an Inside Higher Ed article stating that “this movement is already having a chilling effect on [their] teaching and pedagogy.” The professors reported receiving “phone calls from deans and other administrators investigating student complaints that they have included ‘triggering’ material in their courses, with or without warnings.”

There is a more subtle harm caused to students when professors use trigger warnings. One of us (Haidt) teaches in New York City. Suppose Haidt took his students on field trips all over the city, but every time he took the class to the Bronx, Haidt took additional steps: he gave the class a warning, weeks in advance, and he hired a paramedic to ride with them in the bus. Just in case. What effect will this have on the students, and on their future willingness to visit The Bronx on their own?

Do we really want to tell our students that some of their fellow students could end up in emergency care if they were to read certain novels without being properly steeled for the task? This message would reflect and strengthen the “culture of victimhood” that sociologists have identified as emerging on our most egalitarian college campuses. It could weaken students to the point where we might, someday, really need paramedics in our classrooms.

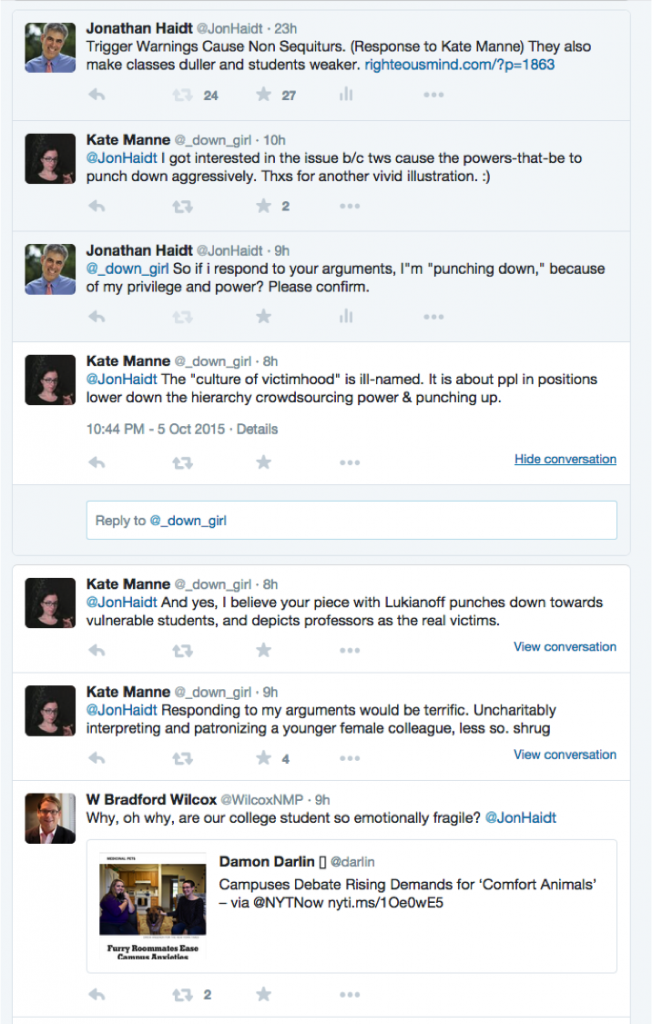

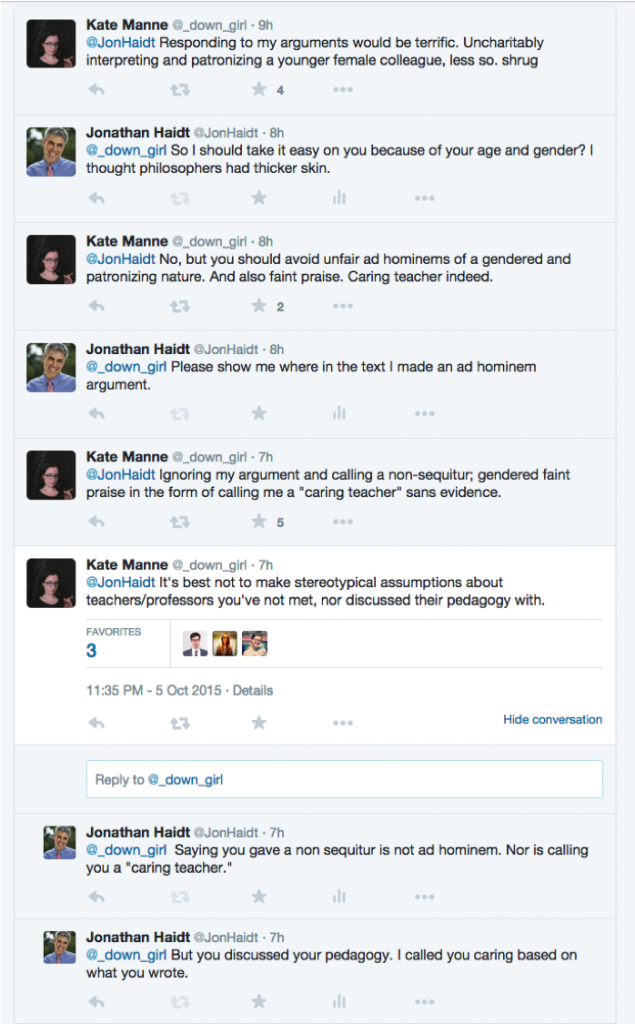

For the record, below is the Twitter exchange I had with Manne as a result of this blog post. Note that Brad Wilcox’s tweet was not part of this exchange — it just happened to be posted during my exchange with Manne.

Read More