Which party owns which words?

I just found a wonderful tool at CapitolWords.org which shows you the frequency with which any word is used in the congressional record since 1996. (Hat tip to Emily Ekins.) You can see which party uses each word more often, and which Senators and Representatives use the word most often. It offers a quick check on the claims I made in The Righteous Mind about how the Left owns Care and Fairness (as Equality), whereas the Right owns the rest of the moral foundations. I’m ignoring the line graphs plotting changes over time (there are hardly any) and I’ll just present the overall pie charts here:

1) THE CARE FOUNDATION

“Care”

“Compassion”

Conclusion: yes, Dems use these words more often.

2) THE FAIRNESS FOUNDATION

“Fairness”

“Justice”

“Equality”

Conclusion: Yes, Dems use these words more, especially “equality.” The words “proportionality” and “equity” rarely occur; there’s no clear word to get at fairness-as-proportionality, which I claim is a concept more valued on the right.

3) THE LIBERTY FOUNDATION

“Liberty”

“Freedom”

Conclusion: Yes, Republicans use these words more. It’s a sign of trouble for the liberal party when liberalism forfeits the word liberty.

4) THE LOYALTY FOUNDATION

“Loyalty”

“Patriotism”

Conclusion: No, contrary to my prediction, Democrats use the words loyalty and patriotism slightly more often than do Republicans.

5) The Authority/subversion Foundation

“Authority”

“Obedience”

Conclusion: No difference on “authority” (which has a great many non-moral uses in a legal and legislative context) but yes on “obedience.”

6) The Sanctity/Degradation Foundation:

“Sanctity”

“purity”

Conclusion: Republicans use these words much more often.

Overall conclusion: This crude measure offers some support for the portrait I painted in chapters 7 and 8 of Righteous Mind: Democrats own the central words of the Care and Fairness foundations, Republicans own the central words of the Liberty and Sanctity foundations. Republicans used one of the two central words of the Authority foundation more than did Democrats, and contrary to my predictions, Democrats used two of the central words of the Loyalty foundations slightly more than did Republicans.

Of course, all of these words are used in many ways, and the next step would be to examine word usage in context. Are Democrats really using the word “authority” in ways that show that they deeply respect authority? For example, the most recent uses in the congressional record on the day I did this analysis are Democrats talking about “a leading authority of Islamic culture” and “Congress has delegated much authority to the D.C. government…” These uses shouldn’t really count. When Jesse Graham, Brian Nosek and I last did a linguistic analysis of church sermons, we found a similar picture: most of our predictions were supported by raw word counts. But once we analyzed words in context and only counted the cases that truly endorsed a foundation, then all predictions were supported.

[Note: in my original post on Aug 9, I used the word “respect” instead of “obedience,” and it showed a trend toward Democrats. But in response to Anwer’s objection below, I tested out “obedience,” which has fewer non-authority uses, and swapped it in above.]

Read More

Polarization leads to nationalization of elections

Do swing states really swing? Are the presidential campaigns right to focus so much time and money on a small set of swing states?

Brad Jones, a graduate student in political science at U. Wisconsin, has produced some extraordinary graphs in a blog post at CivilPolitics.org, showing that states used to swing widely from election to election, particularly in the decades after WWII. Knowing how a state voted in one presidential election didn’t usually give you a strong basis for predicting its vote in the next few elections. So it would make sense for candidates to pour huge amounts of money into the few states that could plausibly be shifted.

But as political polarization has increased since the 1980s, the states have begun to lose their individual personalities and assume their place in a single ranked list, based (I assume) on the percentage of the population that is liberal or conservative. In other words, if you know how liberal or conservative a state is, you can predict with high accuracy how it’s presidential vote will turn out. As Jones puts it:

politics has become increasingly nationalized as it has polarized. This nationalization would explain the stable rankings and uniform shifts that have characterized recent elections. The shifts in election results are not concentrated among the handful of states that receive endless barrages of campaign advertising. Rather, all of the states have tended to move toward the candidate who ultimately wins the election.

You gotta see the graphs to believe it. One really interesting finding: this same pattern of extreme predictability is not new. Jones shows that it also held during the last period of extreme political polarization, in the late 19th Century. Polarization does weird things to our democracy. It makes one moral fault line become highly stable and salient, rather than having multiple possible fault lines and shifting coalitions, which I think is a healthier situation, less prone to demonization.

Read More

The Righteous Mind in One Cartoon

Here’s all 318 pages of The Righteous Mind condensed into a single cartoon,

by Patricia Kambitsch at http://slowlearning.org

Read More

The Working White Working Class Really Is Leaving the Democrats

[See the end of this post for how the debate/discussion has played out… it has been quite civil and productive]

I published an essay in The Guardian two weeks ago offering one reason why most white working class people in the USA vote Republican. Two excerpts:

politics at the national level is more like religion than it is like shopping. It’s more about a moral vision that unifies a nation and calls it to greatness than it is about self-interest or specific policies. In most countries, the right tends to see that more clearly than the left….

In focusing so much on the needy, the left often fails to address – and sometimes violates – other moral needs, hopes and concerns. When working-class people vote conservative, as most do in the US, they are not voting against their self-interest; they are voting for their moral interest. They are voting for the party that serves to them a more satisfying moral cuisine.

I had been inspired by a New York Times column by Tom Edsall, on how Obama’s re-election team had largely written off the white working class vote:

In the United States, Ruy Teixeira noted, “the Republican Party has become the party of the white working class,” while in Europe, many working-class voters who had been the core of Social Democratic parties have moved over to far right parties, especially those with anti-immigration platforms.

My essay was strongly condemned by two worthy critics. First, Andrew Gelman said that I had gotten the basic facts wrong. The working class does NOT vote Republican, he said; it votes Democrat, and has for over 70 years. There’s been no change. And it votes for the Left in most (but not all) countries.

I made a careless mistake in not specifying in my excerpt above that I was talking only about the WHITE working class. That’s the subject of the big debate, ever since Thomas Frank’s book “What’s the Matter with Kansas.” Of course African Americans and Latinos vote heavily Democratic, and make up much of the working class. But even when we focus only on whites, Gelman says I (and therefore Edsall and Teixeira) still got it wrong.

Second, George Monbiot published a rebuttal in The Guardian, saying that whatever the merits of The Righteous Mind, I had stumbled “stupidly and disastrously” in applying my ideas to politics. He pointed to an analysis by political scientist Larry Bartels that refuted Thomas Frank’s claims about the very existence of a shift away from the Democrats of white working class voters. Bartels’ analysis, like Gelman’s seems to show that there has been essentially no change in the allegiance of the white working class to the Democratic Party in the last 70 years. Rather, Monbiot argues, the working class (in Britain and the US) has become less likely to vote at all, because it sees little difference between the economic programs of the two major parties. It would therefore be foolish for the Democrats or the Labour party to try to appeal to working-class voters by “triangulating” on moral issues when what is needed is a stronger shift to the LEFT, to draw them back to the ballot box by offering them a better deal on economic issues.

But was I really wrong in claiming that the white working class has moved away from the Democrats? It all depends on how you define “working class.” All of the authors in question grant that there is no gold standard. You can use education, income, job classification, self-identification, or some combination of those criteria. They all intercorrelate, but different criteria sometimes lead to different conclusions.

Bartels and Gelman focus on income. They operationalize “white working class” as whites in the bottom third of the national income distribution, for any given year of analysis. Gelman’s very interesting book Red State, Blue State, Rich State, Poor State explains the paradox that richer STATES in the USA vote more Democratic, yet within almost all states, richer INDIVIDUALS are more likely to vote Republican. Point taken: there is a robust tendency for people to become more conservative and/or Republican as they get richer (when you hold everything else constant). I had not known this.

Bartels focuses on Thomas Frank’s claim that there has been a “backlash” against the Democrats – Frank claims that the white working class has changed its allegiance in recent years. In chart after chart, based on ANES data from the 1950s through 2004, he shows that there’s been no change, no shift to the right, no abandonment of the Democrats by whites in the bottom third of the income distribution. Once again, there’s no reason for the Democrats to change strategy or reinvent the party because there is no problem to be addressed.

But things look different if you define class based on education. In a paper by Ruy Teixeira and Alan Abramowitz, titled “The decline of the white working class and the rise of a mass upper middle class,” the authors note that taking whites in the bottom third of the total national income distribution (not the white distribution, which can’t be computed from ANES data) gives you an odd sample: the majority of them are not working. It’s mostly students, retired people, homemakers, and people who are unemployed or on disability. In 2004, only 39% of white voters in the bottom third were currently employed (compared to 73% of white voters in the middle third of income). So this is a group that is more dependent on government programs. Bartels’ analyses do indeed show that this group is still and has always been reliably Democratic.

Teixeira and Abramowitz argue that education is a better way to identify the working class. (For one thing, it correlates more closely with people’s own descriptions of their class than does current family income). They focus on whites who have not completed a 4 year college degree. (They also look at other ways of slicing the data, including an index of all the major predictors). Using the lack of a college degree as the criterion, they show that the white working class has indeed shifted over to voting for Republican presidents with Nixon (70% in 1972) and never really returned to the Democrats. Clinton drew about as many of them as did his two Republican opponents, but Gore lost them by 17 points, Kerry lost them by 23 points. Obama lost them by 18 points, and the gap seems to be growing. Nate Cohn analyzes several recent Pew and Qunnipiac polls and concludes: “over the last four years, Obama’s already tepid support among white voters without a college degree has collapsed.” (See also this Gallup poll).

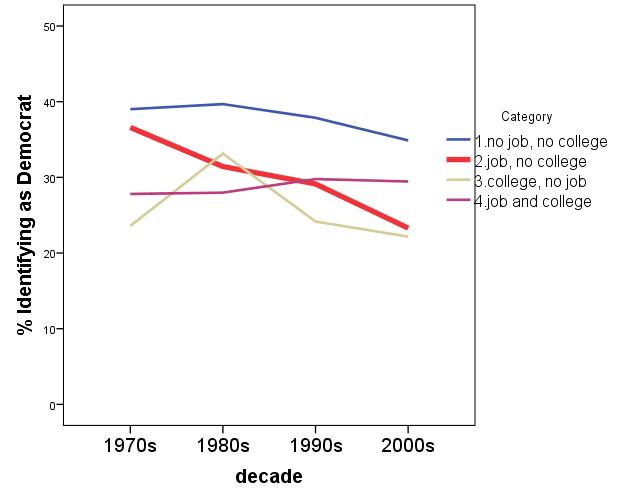

I wanted to examine these relationships in more detail, particularly the difference between employed and non-employed whites, so I downloaded the ANES cumulative data file, limited my analysis to whites, and then created 4 groups based on ANES variables vcf0140a (education level = 6 or 7) and vcf0116 (work status = 1):

Group 1 = no college, no job

Group 2 = no college, job

Group 3 = college, no job

Group 4 = college, job

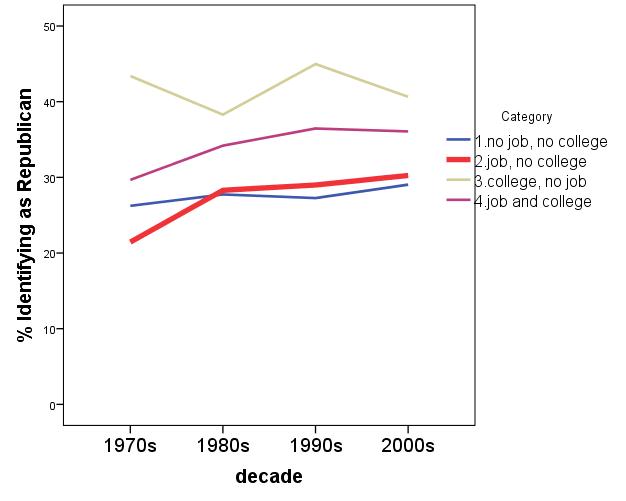

The crux of the debate, therefore, is what has happened to group 2, in comparison to the others. The Democrats have been the party of the working man (and woman) since FDR’s New Deal coalition. So has THEIR allegiance changed in recent decades? The most direct measure for us to look at is ANES question vcf0302: “Generally speaking, do you usually think of yourself as a Republican, a Democrat, an Independent, or what?” Look at the red line below, which plots the declining percentage of people in group 1 who said “Democrat” in response to that question.

When you break up the non-college white population by employment status, as Teixeira and Abramowitz suggest, you see what they are saying: Both of the non-college groups slope downward, but group 2 (the red line) goes down more steeply. White people who have a job but no college degree have been leaving the Democratic Party. Are they becoming Republicans, or just getting disengaged, as Monbiot suggested (about the British working class)?

They are moving toward the Republican Party. The red line slopes upwards. That first sharp uptick appears to confirm the reality of the “Reagan Democrats.” And, interestingly, the purple line slopes upward too. That’s group 4, people with a job and a college degree. In other words, the Republicans are increasingly becoming the party of white people who currently hold jobs. This seems like a dangerous situation for the Democrats. Should they do anything to address it? Or are my critics correct that there no problem here, no trend, no loss of the white working class?

Bartels and Gelman are far more skilled at this sort of analysis than am I. Most likely I have missed something. I welcome their corrections, which I’ll post or link to below. Furthermore, Monbiot, Bartels and Gelman are probably all correct when they say that economic concerns played a stronger role in recent electoral shifts than the sorts of moral/cultural issues that I and Thomas Frank were talking about. I should not have suggested that concerns about national greatness and such things were the MAJOR drivers of change. I should have more modestly said: “look, here are some moral misunderstandings that are probably contributing to the ongoing alienation of many white working class voters from left-wing parties in the US and UK.” I thank my critics for pointing out this serious error in my initial essay, and for doing it in a way that displayed passionate disagreement about ideas without personal animosity or insult.

But the bottom line is that I (and Edsall, Teixeira, Abramowitz, and Frank) seem to have been correct in our basic claim that the white working class is leaving the Democratic Party. Or, at least, it depends how you define class, and it depends on several moderator variables, including employment status. (I assume the trends would be even more dramatic if we exclude unionized and public-sector employees.)

I’m not saying the Democrats must or can recapture the working white working class. It’s a shrinking demographic, many winning coalitions are possible, and I know little about electoral strategy. But the Democrats have been trying to figure out what and whom they stand for, and they’ve been trying to find their narrative, for a while now. (See Matt Bai.) If the Democrats want to be the party of the American working man and woman, they should first figure out whether they are in fact losing the working white working class, and if so, why. Moral psychology may offer part of the explanation.

—————————

Responses

6/17/12: Edsall posted a followup column, backing up his earlier column with analyses of exit polls in congressional voting, showing that swings in the white working class vote predict the fortunes of the Democratic party; swings in other groups are much less predictive. So its bad news for the Dems when this group (“canaries in the coal mine”) turns against them.

6/18/12: Larry Bartels responds here, mostly critical, saying that the trend I show here in party ID is mostly due to the South; it’s very weak outside the south and doesn’t show up in presidential voting.

6/19/12: Political scientist Chris Johnston responds here. He does not disagree with Bartels’ quantitative analyses, but he is supportive of my overall argument. He shows that the moral values items on the ANES do predict voting as well or better than does income, and this happens even among Latino voters.

6/19/12: Nate Cohn comments here, agreeing with Bartels overall but noting that the pattern of changes among white working class support for the Democrats is complex–down in rural areas, up in suburbs–and that since 2008 things are way down mostly OUTSIDE the South.

6/20/12: Andy Gelman responds here, trying to reconcile it all: “In short: Republicans continue to do about 20 percentage points better among upper-income voters compared to lower-income, but the compositions of these coalitions have changed over time. As has been noted, low-education white workers have moved toward the Republican party over the past few decades, and at the same time there have been compositional changes so that this group represents a much smaller share of the electorate.” “Lower-class whites (especially in the south) may well be trending Republican, but upper-class whites are even more strongly in the Republican camp, and it’s worth understanding their motivations as well.”

6/25/12: Edsall wrote a followup NYT column covering this whole debate, and drawing in commentary and graphs from Abramowitz supporting my basic claims (which had been based on Abramowitz’s earlier analyses), and expanding the discussion to include occupation-type (i.e., “blue collar” vs. “white collar.”). My only disagreement with Edsall’s column is that he describes the tone of the argument as “furious.” Perhaps there was furious argument in the past, before I stepped into this “minefield” (Bartels’ term). But the discussion and debate that followed my initial Guardian essay has seemed to me to be very civil. Not just in the dueling blog posts, but in the email discussions among me, Gelman, Bartels, Abramowitz, and Edsall. It has not exactly been a warm discussion among friends, but neither has there been any anger or ad-hominem argumentation. It’s just researchers and a journalist trying to hash out the conflicting signals that emerge from multiple datasets to try to figure out a basic factual question: have the Democrats really been losing the white working class, or is it a statistical illusion that has been too heartily embraced by the press? After all this discussion, I think the answer is still yes–at least for the working white working class. (Gelman has convinced me that the poorest slice of the white electorate has not shifted away). But I see now that the issue is more complicated than I thought when I first stepped into the minefield.

—————————-

Note #1: The ANES dataset has about 1100 white respondents in each election year (every even year) going back to 1948, but some of the items we need for analysis only begin in 1972, so I start there. The graphs look spiky when you plot every single election, so I grouped elections by decade (e.g, 1980 – 1988), and averaged together the 5 elections in each decade.

Read More

I retract my Republican-Party-Bad post

I recently wrote a blog post titled “Conservatives good, Republican party bad.” There was quite a lot of reader push back, from left, center, and especially right. These readers have convinced me that my argument in the post was wrong, and that it was not very “Haidtian” of me to declare one side to be “bad” without a great deal of research, including efforts to solicit counterarguments. I seem to have gotten “carried away” by my liberal inclinations, as SanPete put it. I hope readers will at least allow me to turn this into a useful exercise in which I examine the episode from the perspective of The Righteous Mind.

First, as to why I wrote the post: I had just appeared on the Tavis Smiley show, and to prepare for it I had read Smiley and West’s new book “The Rich and the Rest of Us: A Poverty Manifesto.” The book includes many accounts of people in desperate straits, people who had worked all their lives and now, through no fault of their own, were out of a job and therefore out of health insurance, and in default on their mortgages. It’s heart-wrenching stuff, but I was particularly open to Smiley’s point of view because I was about to go on his show and talk with him, so the “social persuasion link” and the “reasoned persuasion link” of the social intuitionist model were working in tandem. I had stronger feelings of empathy than I normally would have.

The day before my talk with Smiley was taped (April 29) I read the Edsall column. I’ve talked with Edsall several times, and have a working relationship with him, so there too, I’m particularly open to being persuaded by him. And he was citing evidence on empathy collected on YourMorals.org – my research website – as analyzed by my friend and colleague Ravi Iyer. That same day I read the Mann and Ornstein essay in the Washington Post. I assumed (erroneously) that Ornstein was a conservative because he was at AEI, which gave the seemingly bipartisan team of Mann and Ornstein far more credibility in my eyes. So it all came together for me on that day – the feelings of sympathy for the poor and anger at Republican hard-heartedness, which put me into a “can I believe it” mindset, along with a powerful statement from what I thought was a bipartisan team saying that the Republican Party was the problem in Washington, which gave me permission to believe. I could feel my elephant and rider shuffling over to the left. The day after the Smiley interview aired (May 8), I wrote the blog post.

The reader reaction was swift, constructive, and (with the exception of one repeat-commenter) civil. Ben and SanPete pointed out that I was reading Cantor’s remarks in the most uncharitable way, whereas Cantor’s basic point — about the value of having “everyone in,” having everyone contributing even a token amount, is similar to one I made myself in a NYT essay about the value of “all pulling on the same rope” as a way of getting people to “share the spoils” of their joint effort. James Wagner, Tom, and The Independent Whig all pointed out that the Republican stance on “no new taxes” is very much a principled stance, once you understand their decades-long frustration with leaders in both parties who negotiate grand bargains, including spending cuts, but the cuts end up not happening, so spending keeps rising, government keeps growing, and bankruptcy looms ever closer. (I have been persuaded about the fiscal and moral damage done by our entitlement binge by Yuval Levin). So desperate measures, such as drawing a bright line at zero, are indeed backed up by a moral passion which I can respect. You really see that passion in Whig, backed up by a consequentialist analysis of what happens when one side keeps “caring” and spending.

Whig also linked to a point-by-point response to Mann and Ornstein that shows –as usual – the necessity in these complex matters of hearing from an advocate on the other side. One can make a case that the Democrats are the problem, or at least that the two sides are equally at fault for the dysfunction.

I’m not saying that both sides are necessarily equal; centrism doesn’t commit me to splitting the difference, or saying that both sides are always partially right in any dispute. But centrism does commit me to listening carefully to arguments from both sides, and taking my own biases into account, before trying to render any verdict. I didn’t do that. And my knowledge base as a social psychologist would give me no special skills in rendering such a verdict even if I were to put in the time. As James Wagner put it (in a separate email):

“you’re more of a descriptive than a prescriptive guy: I really want to urge you to stay more firmly with your competitive advantage, which is providing information and synthesis that the left and right can both hear well on why we act the way we do. You’re so incredibly good at that, and it’s exceedingly rare. Quite afield from current (or old) event analysis, which is not your bailiwick, which my brother-in-law does better than you.”

Point granted, chastisement accepted.

Well, even if I was wrong to write the original post, at least I can claim that I was wrong for reasons that can be explained by The Righteous Mind. And I hope this episode has an inspiring ending in that the entire debate was carried out so civilly, often with acknowledgment of points on the other side, and with such attention to making claims supported by evidence, that it did in the end change my mind. I never said reason is impotent. I just said that we’re bad at using it by ourselves to find the truth.From page 90:

We should not expect individuals to produce good, open-minded, truth-seeking reasoning, particularly when self-interest or reputational concerns are in play. But if you put individuals together in the right way, such that some individuals can use their reasoning powers to disconfirm the claims of others, and all individuals feel some common bond or shared fate that allows them to interact civilly, you can create a group that ends up producing good reasoning as an emergent property of the social system.

Thanks to you all, for making this blog a reasoning social system.

jon

Read MoreConservatives Good, Republican Party Bad

[NOTE: IN RESPONSE TO THE CONSTRUCTIVE CRITICISMS AND COUNTER-EVIDENCE OFFERED BY READERS BELOW, I RETRACT AND DISAVOW THE POST BELOW. I EXPLAIN WHY HERE.]

A theme of The Righteous Mind and of The Happiness Hypothesis is that wisdom is found on both sides of any longstanding dispute. Morality binds and blinds, so partisans can’t see what the other side is right about. Studying moral psychology has helped me to step out of the “matrix” of my previous liberal team and appreciate the wisdom of social conservatives and libertarians.

But with that said, the last 2 weeks have pushed me to be more explicit about criticizing the Republican Party. First came the extraordinary Washington Post essay by Thomas Mann and Norm Ornstein, titled: “Lets just say it, the Republicans are the problem.” Mann is center-left and Ornstein is center-right, a fellow at the American Enterprise Institute. They are fed up with the press’s fear of seeming biased, which leads journalists to say that both parties are equally to blame for the dysfunction in Washington. But as long-time and highly respected congress-watchers, they believe that the Republican party since Newt Gingrich’s time is mostly at fault for damaging our governing institutions. Here’s a key quote:

We have been studying Washington politics and Congress for more than 40 years, and never have we seen them this dysfunctional. In our past writings, we have criticized both parties when we believed it was warranted. Today, however, we have no choice but to acknowledge that the core of the problem lies with the Republican Party. The GOP has become an insurgent outlier in American politics. It is ideologically extreme; scornful of compromise; unmoved by conventional understanding of facts, evidence and science; and dismissive of the legitimacy of its political opposition. When one party moves this far from the mainstream, it makes it nearly impossible for the political system to deal constructively with the country’s challenges.

The essay comes from their new book: It’s Even Worse Than It Looks: How the American Constitutional System Collided With the New Politics of Extremism. I hope this book is read widely. I don’t think there’s a way forward for our country until something happens that leads to a massive reform of the Republican Party. (This is what Mann and Ornstein said when I saw them speak at NYU last week.)

Mann and Ornstein have been friends since graduate school. I think this is an important point. As I say in The Righteous Mind, personal relationships open our hearts and therefore our minds. They allow us to listen to ideas, and I think this makes the team of Mann and Ornstein a national treasure. Their wisdom is likely to be greater than any partisan — or centrist — operating alone.

The second challenge to the “both sides equal” thesis came in Tom Edsall’s powerful NYT piece, Finding the Limits of Empathy. Edsall reviews data from my team at YourMorals.org, including data analysis by Ravi Iyer, showing that liberals and conservatives who DON’T care about politics are NOT different on their level of empathy, but as people get more partisan, the liberals go up on empathy and the conservatives go down — they get more hard-hearted.

Against that background, Edsall analyzes the recent comments by House Minority Leader Eric Cantor, suggesting that it’s not fair that 45% of Americans pay no income tax, and so perhaps it would be fair to “broaden the base” and make all people pay some income tax. (Even though the poor pay around 16% of their income in taxes when you bring in all the regressive taxes that they pay, from sales tax through wage taxes.)

This bothered me. I can understand that the Republicans are committed to fighting all tax increases. Many have signed Grover Norquist’s pledge, which even prevents them from closing tax loopholes. I can understand “no new taxes.” But Cantor (and rep. Pat Tiberi and others) are happy to consider raising some taxes on the poor, or of shifting more of the tax burden onto the poor.

It seems, therefore, that their stance against new taxes may not be a deeply principled stance. It may be self-interest: no new taxes on the rich. Or, as Edsall suggests, it may reflect a kind of moral class warfare in which the rich are seen as the good people — the providers — while the poor are condemned as the bad people — the lazy free riders. If Edsall is right then this would reflect the abandonment of one of the most cherished American ideals, shared by liberals and conservatives alike: equality of opportunity. Republicans traditionally favored a hand up, not a hand out. They may now favor neither, because they think the poor deserve to be poor.

I have been trying so hard to give the Republicans the benefit of the doubt, given that I spent my whole adult life as a Democrat and know that I am emotionally biased against the party of George W. Bush. But the Mann and Ornstein book, plus the Edsall article, have changed my mind. I now say explicitly that while I find great wisdom among conservative intellectuals from Edmund Burke through Thomas Sowell, I think the Republican party deserves more of the blame for our current dysfunction. (But I’m open to counter-arguments, if anyone can point to a good counter-argument against Mann and Ornstein.)

I first articulated my new position — Conservatives Good, Republican Party Bad — near the end of my interview with Tavis Smiley, below:

Watch Social psychologist Jonathan Haidt on PBS. See more from Tavis Smiley.

Read More

What Evangelicals can Teach Democrats about Moral Development

Anthropologist Tanya Luhrman has a great essay in Today’s NYT, explaining the difference between the secular liberal approach to morality (based on care, given by government) and the evangelical approach (based on self-improvement, carried out within the family and the congregation):

When secular liberals vote, they think about the outcome of a political choice. They think about consequences. Secular liberals want to create the social conditions that allow everyday people, behaving the way ordinary people behave, to have fewer bad outcomes.

When evangelicals vote, they think more immediately about what kind of person they are trying to become — what humans could and should be, rather than who they are. From this perspective, the problem with government is that it steps in when people fall short. Rick Santorum won praise by saying (as he did during the Values Voters Summit in 2010), “Go into the neighborhoods in America where there is a lack of virtue and what will you find? Two things. You will find no families, no mothers and fathers living together in marriage. And you will find government everywhere: police, social service agencies. Why? Because without faith, family and virtue, government takes over.” This perspective emphasizes developing individual virtue from within — not changing social conditions from without.

As I tried to explain in chapter 8 of The Righteous Mind, the utilitarian individualism of the secular left turns off most voters. The thicker, more binding morality of social conservatives is more broadly appealing. It may even be a better recipe for producing more virtuous, self-controlled citizens, who end up creating the best consequences for the nation as a whole. This is what I was trying to describe in chapter 11 as “Durkheimian utilitarianism” — it’s a way of maximizing overall welfare that takes human nature into account.

Read More