Trigger Warnings Cause Non Sequiturs

Below is the letter to the editor that Greg Lukianoff and I submitted to the New York Times in response to an op-ed by Cornell philosophy professor Kate Manne, which defended the use of trigger warnings.

The Times did not respond to our submission, so here it is:

To the Editor:

Re: “Why I use trigger warnings” (Opinion, Sept. 19): Kate Manne’s efforts to alert her philosophy students about potentially upsetting course content shows her to be a caring teacher. But her critique of our essay condemning trigger warnings begins with a non sequitur. She is surely right that “the evidence suggests” that some of her students “are likely to have suffered some sort of trauma.” But that does not logically imply that “the benefits of trigger warnings can be significant.” We have not found any empirical evidence that trigger warnings yield any psychological benefits, whereas there is empirical evidence suggesting that they might be harmful. So it is more logical to conclude that if trauma is common, then the harms caused by trigger warnings might be significant.

Manne then offers an analogy: “Exposing students to triggering material without warning seems more akin to occasionally throwing a spider at an arachnophobe.” This is not a valid analogy. Asking students to read novels or Greek myths that include sexual assault is like saying the word spider in the presence of an arachnophobe, which anxiety experts tell us is a good way to reduce the long-term emotional power of spiders. If well-meaning teachers and friends work together to help an arachnophobe avoid exposure to the word spider, or to pictures of spiders, spider webs, and Spiderman, they will strengthen the arachnophobe’s conviction that mere reminders of spiders are dangerous. This is how a temporary and reversible phobia can be hardened into a lifelong and debilitating identity.

Manne also asserts that “there seems to be very little reason not to give these warnings.” It’s simple courtesy, no? Trigger warnings are like “advisory notices given before films and TV shows.” But those warnings are given so that parents can keep their children safe from material for which they are not yet emotionally mature enough. This is why the American Association of University Professors has condemned the use of trigger warnings as being “at once infantilizing and anti-intellectual.”

Furthermore, once a few professors start giving these warnings, students will begin to request them from their other professors, and this may lead to a cascade of caution among the rest of the faculty. Last year, seven humanities professors from seven colleges penned an Inside Higher Ed article stating that “this movement is already having a chilling effect on [their] teaching and pedagogy.” The professors reported receiving “phone calls from deans and other administrators investigating student complaints that they have included ‘triggering’ material in their courses, with or without warnings.”

There is a more subtle harm caused to students when professors use trigger warnings. One of us (Haidt) teaches in New York City. Suppose Haidt took his students on field trips all over the city, but every time he took the class to the Bronx, Haidt took additional steps: he gave the class a warning, weeks in advance, and he hired a paramedic to ride with them in the bus. Just in case. What effect will this have on the students, and on their future willingness to visit The Bronx on their own?

Do we really want to tell our students that some of their fellow students could end up in emergency care if they were to read certain novels without being properly steeled for the task? This message would reflect and strengthen the “culture of victimhood” that sociologists have identified as emerging on our most egalitarian college campuses. It could weaken students to the point where we might, someday, really need paramedics in our classrooms.

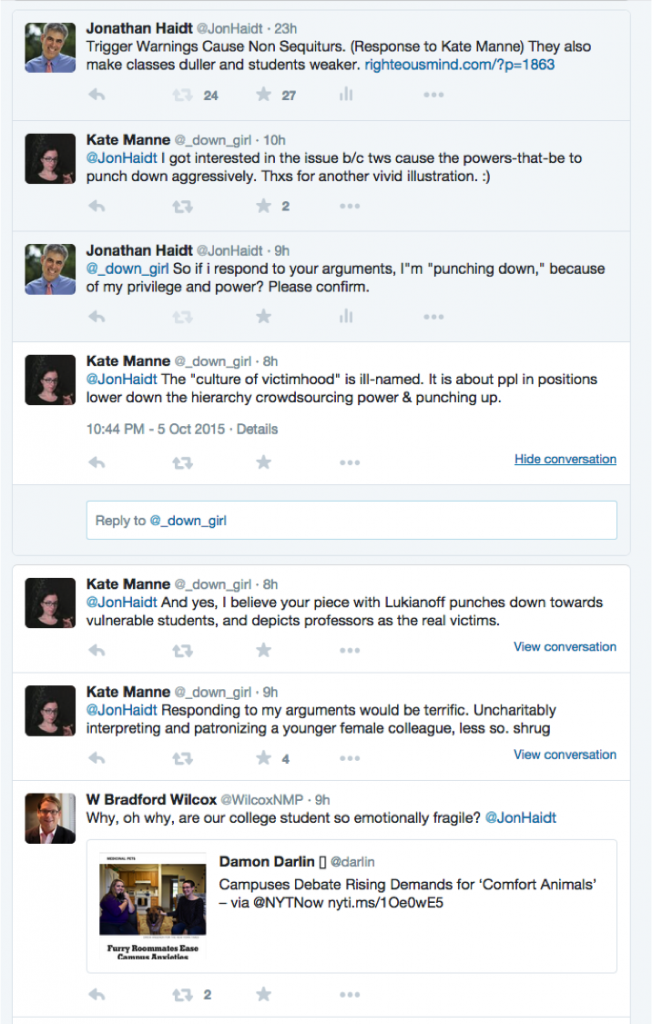

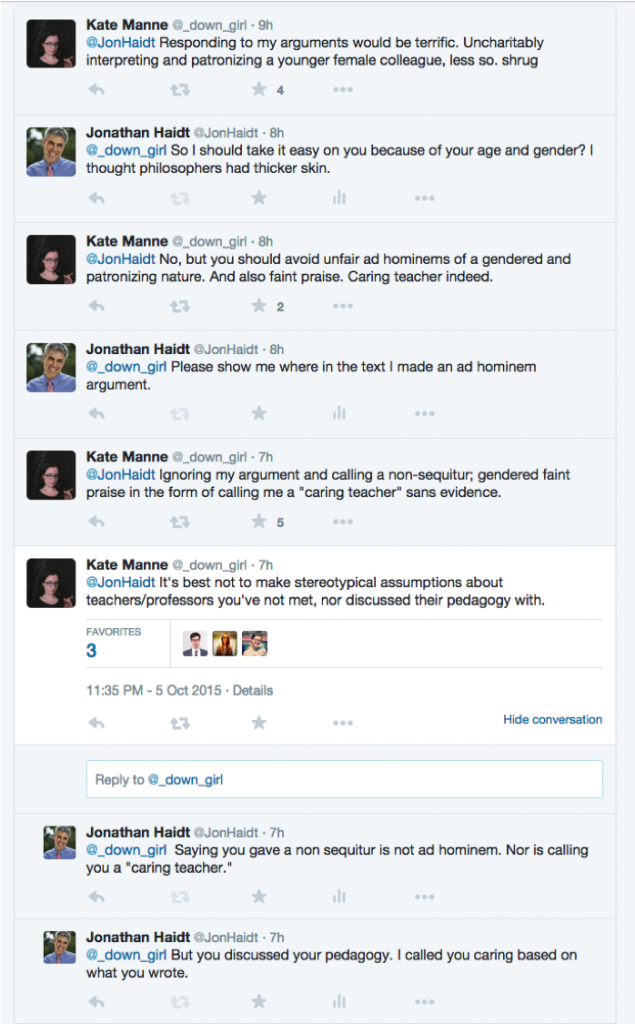

For the record, below is the Twitter exchange I had with Manne as a result of this blog post. Note that Brad Wilcox’s tweet was not part of this exchange — it just happened to be posted during my exchange with Manne.

I’m surprised that a university professor of philosophy (Kate Manne) would call Haidt’s letter an ad hominem attack. It was nothing of the sort. My sense is that Manne would rather toss around buzz words and phrases (“puching down”, etc.) than address Haidt’s arguments directly. It is very discouraging to see a university professor respond in such a fashion.

Yes, it was bizarre. It’s a pattern of thought I have come to see as “Marcusian”, after Herbert Marcuse, who taught ways of shutting out opposing ideas, rather than engaging with them: http://heterodoxacademy.org/2015/09/23/how-marcuse-made-todays-students-less-tolerant-than-their-parents/

Well, doesn’t your letter contain a number of little ironical jabs which can plausibly be interpreted as having an ad hominem thrust? You seem, for example, to suggest that Manne is lacking in “courtesy,” that she is an “anti-intellectual,” and that she “infantilizes” her students. Such possible implications might have been appropriate back when people engaged in what they liked to call “debates,” but today it arguably goes beyond what is properly allowable in a purely professional exchange between academics.

To your credit, though, you did at least submit your letter under your own name. If a disorderly student who agreed with you had resorted to provocation and sent out inappropriately deadpan “parodies” in Manne’s name (e.g., “I confess I’m an anti-intellectual and I like to infantilize my pupils. But hey, that’s just part of the politics of being a practitioner of feminist philosophy in today’s academic world. I hope you will all support my position and denounce those who are criticizing me”), he or she would certainly be facing hard time in prison—thanks to the progress made in this area by several NYU officials and leading New York prosecutors. See the documentation of America’s leading criminal “satire” case at:

http://raphaelgolbtrial.wordpress.com/

Ummm, no, the letter doesn’t contain ad hominem arguments in its ‘ironical jabs’. People are allowed to disagree. He is arguing against trigger warnings, not insulting Manne personally. He believes trigger warnings have negative effects; is he not allowed to cite these negative effects because they automatically constitute personal insults of its supporters?

Even straight out saying someone is an anti-intellectual or lacks courage – which Lukianoff & Haidt don’t do – would not be an ad hominem in itself. For such a labeling to be an ad hominem would require the labels to be used as a justification for why the person’s argument is false. Lukianoff & Haidt clearly have better arguments than that.

Such distinctions might have been pertinent back when people engaged in what they liked to call “robust debates,” but today they are regarded as justifications for going beyond what is properly allowable in a purely professional exchange between academics. To suggest that Manne lacks “courtesy,” that she is an “anti-intellectual,” that she “infantilizes” her students? Surely such remarks are inappropriate among collegial peers, particularly when addressed to younger members of the community or women, two groups that should certainly be treated with a degree of delicacy. True, pending next year’s inauguration, the law might currently allow such trigger-speech, while drawing the line at inappropriate satire and accusations of misconduct; but it must be hoped that among colleagues we can do better, when the very fabric of polite society is at stake.

Unfortunately that’s another off-base and (again) weirdly presumptuous conjecture about me as a thinker and teacher on Haidt’s part. As it happens, I not only assign but also insist on a charitable discussion of political conservatives’ writings alongside progressives’ in my courses — assigning, e.g., Haidt and Lukianoff, Conor Friedersdorf, and Jonathan Chait (an increasingly conservative-leaning liberal), in discussing the ideology of the so-called culture of victimhood and the issue of political correctness in my contemporary moral problems course this semester.

As for my criticisms of Haidt’s response to my op-ed, I was disappointed by his lack of engagement with the substance. In the above post, and later on twitter, Haidt chose to indulge in holistic characterizations of me — the thinker and teacher — as insufficiently thick-skinned to be a philosopher (yeah, my fragility… that’s why I chose to submit two op-eds to the NYT in the last year…), and as illogical (despite my training as a logician). The accusation of having (been caused to have?) committed a non-sequitur is also unfair, given its basis in the false and uncharitable assumption that the word “so” in a sentence near the beginning of my article marks the end of the argument, rather than a conclusion which I then go on to argue for in the remainder. But that is why the rest of the article exists, as a moment’s reflection might have suggested. Overall, Haidt failed to engage in a fruitful disagreement with my position, and instead primarily resorted to finding reasons to ignore or dismiss my arguments (which is perhaps why the NYT chose not to give him the right of reply — but here I only speculate).

One of the points I went on to make was that I use trigger warnings to promote rational engagement for all of my students, when the content (e.g., graphic descriptions of sexual assault, in material I assign about one of my main research areas, misogyny) could reasonably be expected to be what I called ‘rationally eclipsing’ (e.g., by inducing panic) for some people without prior warning. What Haidt somehow inferred from this is that I am a caring teacher who likes students not to be upset by the novels(?!) I’m assigning. Calling me a “caring teacher” is not an “attack” (a word I never used, incidentally), but it is yet another holistic characterization of me — the thinker and teacher — which is false, patronizing, and hence unfair (or at least constitutes faint praise) in this context. While I do consider myself a caring teacher, I am also one who tries to challenge students at every opportunity to think through the ugly realities of misogyny, sexual violence, and social hierarchy (as I said on twitter, in replies of mine which strangely appear to have been omitted from those above). The full exchange can be found here: https://twitter.com/_down_girl/status/651195228225802240

Finally, the empirical evidence Haidt refers to in the article linked above is embarrassingly thin and often bears no relation to the use of trigger warnings. For some suggestive and actually relevant studies, the references here provide a useful jumping off point: http://www.asc41.com/Criminologist/2013/2013_July-August_Criminologist.pdf

An American ideological universe which labels individuals such as Jonathan Haidt, Greg Lukianoff, Conor Friedorsdorf and Jonathan Chait as “political conservatives” would be like a cheese shop which exclusively stocks only varieties of Gorgonzola.

I read professor Haidt’s response above before reading assistant professor Manne’s NYT OpEd. I purposed to be fair minded and objective to both points of view before developing my own.

Both were articulate and well written, which I expected form degreed authors. OF concern however was the lack of any evidence for Manne’s assertion

“The evidence suggests that at least some of the students in any given class of mine are likely to have suffered some sort of trauma, whether from sexual assault or another type of abuse or violence. So I think the benefits of trigger warnings can be significant.”

There is no logical connection in her statement, surprising having originated from a trained logician. I came away pondering that Manne added the jargon “evidence” to obfuscate a lack of intellectual integrity, where there was no evidence for her assertion; “So I think the benefits of trigger warnings can be significant.”

If the evidence exists pleas by all means produce it. Professor Manne where can we find the evidence that you have found so helpful?

On the other hand professor Haidt presented a well reasoned rebuttal, complete with references, which I also examined. His references were appropriate, and corresponded to Haidt’s assertions and conclusion.

As of yet I can not formulate a final opinion until I can examine assistant professor Manne’s evidence, unless of course it does not exist.

Assistant Professor Manne, please reveal your source evidence to allow us to examine the basis for your conclusion so we may come to a conclusion of our own.

Ms Manne, I’m no philosophy prof or any sort of academic heavyweight, but it seems to me that your fine-grained subjective analysis of criticism of your position seems beneath the station you hold. If I was charged with learning in your class, I’d withdraw and find another less childish teacher. Talk about tangents. Are the trigger warnings going to be on the exam?It’s so ridiculous I can’t believe you didn’t demand a retroactive trigger warning for your perceived slighting. Your salary would appear to be money straight down a drain. The worst part is, you seem to be in good company, being that all the kids raised on fake participation trophies and ‘everyone’s a winner’ have grown up and decided that a good career to pursue would be one in which the bulk of the focus is on handing out life-participation ribbons to their college-aged students. It’s a scam, Ma’am. And I will cop to being a meanie and a jerk is this missive because your ilk is insufferable and is damaging the upper limits of human potential.

You (Kate Manne) offer a compelling account of what trauma is like to experience, and why, when in a state of trauma, someone would not be able to focus on academic work. You also make a compelling point that trigger warnings are not especially unique in substance and that they do not harm those to whom they are not intended to apply. There is also (obvious) reason to believe that, given a trigger warning, someone would be able to avoid the material that they believe to be triggering. It is not obvious, however, that it is beneficial to them to avoid that material. It is also not obvious that they could be effective participants in the class without reading the (allegedly) triggering material, nor is it obvious that their learning experience would not be negatively affected (and perhaps substantially so) by avoiding the material. It’s also not obvious that, even if we assume that people w/trauma should avoid reading the things that you or others dub potentially triggering, that those people will make use of it, or that others will not avoid engaging with the material out of a purely political belief that they are trauma victims. You also don’t even seem to provide sufficient specification about the potentially triggering material, and even if you do, you assume, without a shred of evidence, that you, with no psychological credentials, know exactly what will be triggering for students and what won’t.

In essence, you effectively make the points that:

a) some people suffer from trauma

b) trauma is bad and inhibits productivity, including academic work

c) including trigger warnings will help people avoid material that they believe will trigger them, should they so choose.

You, however, avoid making, or successfully making, the following arguments:

a) It is beneficial for students to avoid material that will trigger them (assuming that you provide sufficient specification such that they know exactly where anything that will cause them to enter a traumatic episode is)

b) That everyone who “needs” to do this will, and that people who don’t won’t avoid material that they (wrongly) believe will “trigger” them, causing them to unnecessarily avoid learning new academic material

c) That you and other non-psychologists are endowed with the insight to know exactly what will be and will not be triggering for others.

It is in the absence of the latter three points that your argument collapses entirely.

It is also worth noting that your twitter exchange w/Haidt use the, frankly, anti-intellectual and fundamentally Marxist simplifications of power analysis by using the terms “up” and “down” to attempt to describe the power dynamic between Haidt+Lukianoff and those whom they describe. To do so is intellectually equivalent to invoking the Christian “god” for an argument in the secular domain – it holds zero value. Also, as someone else said below, if you believe that Haidt, Lukianoff, Friedorsdorf, and Chait are “conservatives”, then you are either deliberately re-defining the word “conservative” w/o telling people to suit your agenda, or you have a complete lack of understanding of American/western political thought. I say this not because of what you want/do, but your justification for it, but I have serious questions as to whether or not someone who would present that obviously weak of an argument is qualified to be a professor of Philosophy.

“caring teacher” -> “caring” but “dull” teacher (in the penultimate paragraph)

With all due respect, as the parent of a university student, I would find this entire exchange more engaging if I had come away feeling strongly about the relative merits of what my offspring are experiencing, rather than feeling strongly about the relative merits of the protagonist professoriate. Who said what to or about whom in, say, the Huntington’s Disease research lab isn’t nearly as interesting as what results are coming out of the lab, hence, only the lab results are shared publicly. I’m not quite sure why the same is not true in social science, but for the record, then, let me say: most of us really only care about the science.

If the amount of time and energy someone spends on a single issue can be seen as representative of the importance they give to that issue relative to all others in their argument, then Manne’s interpretation of Haidt’s use of the word “caring”, ascribed to her in the opening paragraph of his rebuttal above, seems to rate quite highly in the hierarchy of her arguments. This is unfortunate. First, the only thing we can say with any certainty about the statement is that Haidt was describing Manne as an apparently “caring” teacher, based on what she had written in her article. To those of us so inclined to make certain assumptions about the nature of civil debate– as well as the technique of hoping to gain credibility, or just establish a civil tone to his rebuttal, by either conceding a well-argued point or (in this case) noting the good intentions behind their opponent’s original premise– Haidt’s statement was as benign as it was irrelevant to the arguments on either side. The negative meaning Manne very clearly attributes to the comment doesn’t follow logically… assuming that 1) we all have the same understanding of what we’re talking about when we use the word “logic”, and 2) we are all equally ignorant of Haidt’s tone of voice when delivering the sentence. That’s one of the failings of purely written communication: tone of voice and intention aren’t always clear enough to form an opinion. The proper thing to due in such a situation would be to ask for a clarification. But Manne doesn’t do that. Instead, she forges ahead– and sticks to her interpretation even after it was explained, merely choosing other pathways to the conclusion that “caring” is somehow used as a slight. My understanding of one of those must be wrong, because the insult morphs into “You’re insulting me by making a blanket judgment on the type of person I am”… even though that judgment is positive and intended to be a benign interpretation of what Manne thinks of herself, as implied by her reasons for using “trigger warnings” in her original article. But maybe I misunderstand what she is saying. Then she goes on to say that Haidt is in effect calling her or her teaching “dull”, as a result of a statement she refers to but that I can’t find anywhere. Regardless, the fact that she didn’t either ignore the comment or ask for the necessary clarification (which someone inclined to interpreting any judgment as negative and insulting would need for logically valid confirmation of their assumption) detracts in no small measure from her other arguments as well, since she sets herself up as being so hyper-vigilant against slights– real or perceived– to see them everywhere and refuse to accept that they were anything other than slights. This and the other qualities referenced below that Manne uses to form her opinions have the appearance of paranoid, black-and-white, and mind-reading cognitive distortions. It’s as if Haidt had actually called her “a name”, or made a direct ad hominem attack. He did neither. Try as I might I just can’t find the subtext that Manne reads into not only this simple comment, but much of Haidt’s response. In fact, I find the overall tone of her engagement to be hostile. Among the only truly ad hominem attacks I could find was the petty, passive-aggressive jab that Manne takes at Haidt by her appeal to the authority of the NYT op-ed editor being used for adjudication, her implication being that the editor’s decision was based on the relative merits of Manne’s and Haidt’s arguments. No, that’s not me reading into what she did there and committing the same error as she did through her paranoid interpretation of “caring”. Manne’s intention is perfectly clear, otherwise there is absolutely no reason for including it and it would be a true non-sequitor. In addition, using descriptions such as “weirdly presumptuous” and “embarrassingly thin” are ad hominem attacks as well. Just because she is letting the adjectives do the work doesn’t make what she is doing any less of an attempt to perform an end-run around logic by reverting to rhetoric in order to come out on top in an argument. I’m surprised at the self-deception (at best) or intellectual dishonesty (at worst) of someone tasked with educating students under the rubric of “Philosophy”. Apparently, this use of the term “Philosophy” is closer to the colloquial use as “opinion”, than to the study of argument employing rigorous logic and not just persuasive speech of any kind, logical or not.

Thank you for your continued, intelligent coverage of this problem Professor Haidt.

“We have not found any empirical evidence that trigger warnings yield any psychological benefits, whereas there is empirical evidence suggesting that they might be harmful. ”

Your claimed ’empirical evidence’ against trigger warnings doesn’t say anything about trigger warnings.

If you are going to be so loose about what constitutes supporting empirical evidence then we can apply the same standard in the opposing direction. If, as you claim, exposure therapy offers evidence for the negative value of trigger warnings, then other interventions with evidence for being beneficial to PTSD that do not involve ‘exposure’ can be considered too – such as exercise, mindfulness, medication, counselling etc.

Exposure therapy is not the same thing as exposure. The word ‘therapy’ gives that away, and it tells us that the exposure probably needs to be facilitated by a trained therapist. Even if a lecturer happened to have such expertise, it wouldn’t necessarily follow that exposure would be appropriate to all individuals with trauma. If it was, exposure therapy probably wouldn’t be an issue of such contention among trauma therapists*. But again, just because exposure therapy appears to be beneficial for some trauma patients, it doesn’t follow that all forms of exposure are helpful.

You have written about biases, but I wonder if you have picked up on your own confirmation bias. You are clearly passionate about important issues involving free speech and academic liberty, but perhaps your arguments would be stronger if you focussed on those points rather than making non-sequiturs of your own regarding mental health.

* Becker C.B, Zayfert C., & Anderson E. (2004.) A survey of psychologists’ attitudes towards and utilization of exposure therapy for PTSD. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 42(3); pp. 277-292.

Even if so-called “exposure” had no effect on the actual psychological trauma as you suggest (I have no idea, I’m not a psychologist), I think it undeniably negatively affects your intellectual and social development. Namely, students are getting used to the fact that they can always look to an authority figure to help them.

The factual basis of the claims regarding PTSD seem to have little importance in the fact that we’ve clearly got a generation who’ve been conditioned to be morally dependent.

When they’re capable of inventing these “micro-aggressions” out of thin air (see Yale halloween nonsense), what difference does the success of curing genuine PTSD really make? They’ll just invent something new to replace it, because that’s what they’ve been incentivised to do.

I think trigger warnings are one of the best cultural compromises that we’re going to get. They allow adults to control the material that they’re exposed to. Saying that adults _shouldn’t be able to do that_ is infantalizing, if people want that control. We have no moral duty to carry out aversion therapy on individuals who actively do not desire it. Trigger warnings also allow free speech, with the burden placed on the listener if they want to avoid a particular argument.

This seems like an entirely functional standard of courtesy.

For Kate Mann, pardon this interruption by an obvious neanderthal, bgut you are full of shit, and perpetuate the axiom that “those who can, do, and those who can’t, teach.

I’m not the brightest bulb in the light fixture so rather than try to firure some things out I look to history for answers already found.

History gives us uncoddled kids who, at age 18 in 1944, were capable of jumping out of airplanes, storming beaches, and putting their lives on the line daily, sometimes hourly.

Spring forward slightly more than half a century and garbage like “trigger phrases”, microagressions”, etc give society weak pablum suckers useless for much of anything…which, I suspect, is your intent, the creation of a generation thaat has no choice but to rely on some all-knowing entity (read: government) to protect them and direct that in all things.

Yoy, Ms Mann, are a complete waste of oxygen.

There’s another fault in Manne’s psychological reasoning that you didn’t point out, besides her false analogy between mentioning a feared stimulus and exposing someone directly to it (i.e., throwing a spider at an arachnophobe). She claims that exposure to something scary essentially shuts people down and makes them unable to reason through a class discussion, whereas angering people is not a problem. If anything, psychological research shows that the opposite is true. When people are anxious they become more vigilant and actually become more careful processors of information (in the persuasion literature, social psychologists talk about how fear appeals can be effective because they cause people to take the “central route to persuasion” and process information more carefully). However, this literature shows that anger does not have that effect. When people are angry, they rely on simplistic labels and slogans, and are less likely to rationally consider a point of view (i.e., anger causes people to take the “peripheral route to persuasion”). I am not advocating that we avoid possibly angering our students for this reason, but I think the arguments not to piss people off are stronger than the arguments not to scare them.

This exchange indulges in a lot more heat than light, I’m afraid. The following ought to be fairly obvious:

1. Manne’s argument is not the non sequitur claimed by Haidt and Lukianoff. It does not proceed, as they seem to think, from “Many students have suffered trauma” to “therefore trigger warnings are helpful.” The argument is more like this:

“The thought behind trigger warnings isn’t just that these states are highly unpleasant (although they certainly are). It’s that they temporarily render people unable to focus, regardless of their desire or determination to do so. Trigger warnings can work to prevent or counteract this.” (from the Manne piece)

Therefore, trigger warnings are helpful. Call this a weak or unsupported assumption if you like (I believe it is both), but the argument of the essay isn’t a non sequitur.

2. H&L did not make an ad hominem argument. Calling Manne a “caring teacher” is not an insult or a slight.

3. Saying “You’re punching down, therefore there is something wrong with your argument” may not be an ad hominem, exactly, but it’s closer to being one than anything H&L wrote.

4. There is no good empirical evidence about whether trigger warnings are beneficial, on either side. Manne’s unsupported assumption about how trigger warnings help students does not count as good empirical evidence, but neither does the rather strained analogy H&L draw to CBT and exposure. We just don’t know what effect trigger warnings have, for good or for ill. That question hasn’t been studied, and the questions that have been studied are not closely related enough to draw any conclusions.

5. As a result of 4, to say that trigger warnings are “good practice” is silly. To say that they are “bad practice” is equally silly. Criticizing colleagues for using them or not using them, in the absence of any evidence, is bad practice.

Great comment. I don’t think Haidt really wins his case here, as you say. However, I also think that he argues in a better and more responsible and inclusive style than Manne. Manne’s invocation of ‘punching up’ and ‘punching down’ and her somewhat bizarre effort to interpret ‘caring teacher’ as an insult are an attempt to shut down disagreement through essentially authoritarian speech control. Tendentious and heavily ideological interpretations of who supposedly holds more power are supposed to determine who is allowed to say what. Rather than engaging directly with the arguments.

Great summary. As a very liberal minority female who is ideologically predisposed to supporting Manne, I can agree that the strongly defensive and somewhat indignant tone of her response did more to undermine the credibility of her argument and typecast her as a flag-bearer for a “culture of victimhood” than anything Chaidt stated in this exchange.

That said, I’d like to point out that the strongly dismissive and antagonist tone of some of the commenters here (“neanderthals” and people questioning her worthiness to be a professor) should offer some hints into how Manne’s worldview would leave her sensitive to perceived condescension.

We should each try to “be the change” and engage in civil discourse, or else admit the hypocrisy of vituperously criticizing our intellectual opponents because of their “tone.”

When I was at boarding school, I suffered constant panic attacks. EVERYTHING was a trigger! Eventually, I learned that in order to function in the way that I wanted to while I was on this earth, I had to set about changing how I reacted to the world, since changing the world around me was not an option. Fast forward 20 years, the other day I was standing on a pretty full commuter train with my very well behaved dog sitting quietly by my side. A lady, sitting several seats away, piped up with this information: “I don’t like dogs.” Naturally, I just thought she was mad, and said nothing. “I’m not happy,” she continued. But then I realized that in this corner of England, not everyone was crazy: I caught the eye of a few people who smirked and rolled their eyes. Someone giggled. It made my week.

I can see that trigger warnings might be useful to certain people – but the onus should be on the individual, not the institution. Simply rock up at college and explain to tutors that you were the victim of violent burglary/sexual assault/terrorism/race-hate crime/bereavement/family argument/tiff in a restaurant/road traffic accident/road rage/harsh telling-off/divorce/job-loss/scary airplane moment/stressful court case/stressful week/tricky situation with an distressed animal/kettle burn/paint smudge/domineering father/disinterested mother.

Or you can take ownership of your own feelings and realize that from time to time, your world will be rocked, from the large to the small, and it is up to you to decide whether other people should be held responsible for your upset.

Anything can be (pretty much everything is) a trigger (at least from one of the sides in these “fights”) when the direction of the punch is the thing that matters most, not the thrust behind the punch itself. Such a shame that this is what so much of “academic” thought is now reduced to.

I’ve always found these trigger warning debates really strange. So, alright, first, I have claustrophobia to a degree that if I have to lie still in a very small space (think: dental chair with people looming over, MRI machine, that sort of thing; not elevators) I panic to the point where we can’t finish whatever we’re doing. The more I try to force myself, the further I get into “flight or fight” mode, to the point where– not to get TMI or anything– my body will, er, empty itself so I may more readily run away. I tried CBT, I tried meditation, but ultimately what gets me through it is good ol’ drugs.

I definitely appreciate knowing that I have a medical appointment ahead of time so I can load up on benzos or nitrous, but I can’t imagine participating in a class in that state. Nor can I imagine participating in a class while having a panic attack. Which sort-of makes me think, maybe a serious mental illness of this kind should be regarded like physical illness, like pneumonia. The student can get FMLA (or the equivalent) to treat his or her mental illness like the medical condition it is, and then either return to school having healed, or return and choose a course of study that isn’t hindered by their condition (I would not major in spelunking, for example), or realize that their health is such that they cannot attend school for now.

Being unable to attend school due to illness isn’t shameful. It can be frustrating, for sure, but it’s sometimes necessary.

The trigger warning proposal seems to assume that mental illnesses are actually disabilities, which legally must be accommodated for students. I’m 100% in favor of accommodating students with disabilities– I’ve been in classes where all videos had subtitles, and spoken lectures and class discussions were transcribed and projected onto a screen for deaf students. This didn’t affect me (a hearing student) one way or the other, and it helped the deaf students successfully participate in their education. Same way with elevators and classroom size standards for students who use wheelchairs and walkers, or e-reader compatible editions of textbooks for blind students, or alternate testing environments for students with sensory processing disorders or executive function disorders. None of these things negatively affect able-bodied students, and they work positively towards the goal of educating all students.

But panic attacks– much like asthma attacks or allergic reactions– are difficult to prevent without medication. They can be made less frequent over time with long-term therapy, but nothing done in the classroom in the span of a few sentences can prevent panic attacks if a student has a real mental illness. So, just as I would recommend that a student who had several asthma attacks per week should take a semester off to heal and address an underlying respiratory illness, a student who has a panic attacks in a typical classroom setting should do the same. That’s the important distinction between an illness and a disability, and it’s a very relevant distinction in terms of policy.

Now, here’s the other thing: if a student is merely experiencing anxiety / nervousness / flusteredness, or even fearfulness, that’s not a panic attack. I’m sure trigger warnings could, at least in some cases, quell nervousness and cultivate a calm, level-headedness that could help class discussion. And figuring out the answer to the question, “how can a professor cultivate a calm discussion on controversial topics?” is a good one.

But, equating that nervousness with a physical state where someone’s heart-rate shoots up, they sweat profusely, they shake, collapse, sometimes lose control of their bladder or bowels, sometimes dissociate (begin to feel that what is happening isn’t real or is a dream), often straight-up bolt or punch someone– that’s like comparing a cold to cancer. It’s incredibly disingenuous, and I think most people know that.

Most people who experience traumatic life events actually don’t develop PTSD or a panic disorder. Why some do and some don’t is a question scientists and doctors are still exploring. Also, in rare cases, a panic disorder seems to be entirely medical in nature, with no initial environmental cause. All of which means that it’d be strange to assume that in most classes there is a student who experiences panic attacks, and it’s presumptuous to prescribe a “treatment” (whether it’s trigger warnings or exposure) without the students’ foreknowledge. In my experience, students with either disabilities or illnesses tend to be upfront and proactive about what their condition is and what they need, and reasonable at coming to workable compromises if they can’t get their first-choice accommodation. Like, if a student says, “I’m deaf, so I can’t understand lectures; can I get an ASL interpreter?” And the prof says, “Currently we don’t have any ASL interpreters employed here; is it alright if we get a stenographer to transcribe discussions in real time and project them on a screen?” The student will usually be like, “Sure, that works.”

I suspect it works just as well with students with panic disorders and other mental illnesses.