Country of ambition and pollution

I’m traveling in Asia for three months to do research for my next book, Three Stories About Capitalism. Each Westerner gets just one chance to have first impressions of China, and mine lived up to my hopes for memorability.

To prepare for the trip, I’ve been reading Evan Osnos’ much-talked-about book Age of Ambition. It’s about how China is changing as the market-oriented reforms initiated by Deng Xioping in 1979 have led to such rapidly rising prosperity–and ambition for far more prosperity–since the 1990s. Osnos opens the book by describing the “fever” of aspiration that was sweeping the big cities when he first arrived in 2005. It was the “belief in the sheer possibility to remake a life,” by rapid success in business. These new possibilities are changing everything, including dating. We learn about a dating show in which a young woman brushes off an appeal from a suitor who talks about taking her out on his bicycle. The woman says “I’d rather cry in a BMW than smile on a bicycle.”

So I was well prepared to encounter a country abuzz with energy, entrepreneurialism, and materialism, with little trace of communism. But I didn’t expect the evidence to hit me as soon as I boarded the China Southern flight in Kuala Lumpur, to fly via Guangzhou to Shanghai:

1) When I sat down in my seat, the seat protector in front of my face had an advertisement for marble tiles, because the sort of person who can take a plane is probably also renovating his home or apartment in a lavish Western style (as their website makes clear).

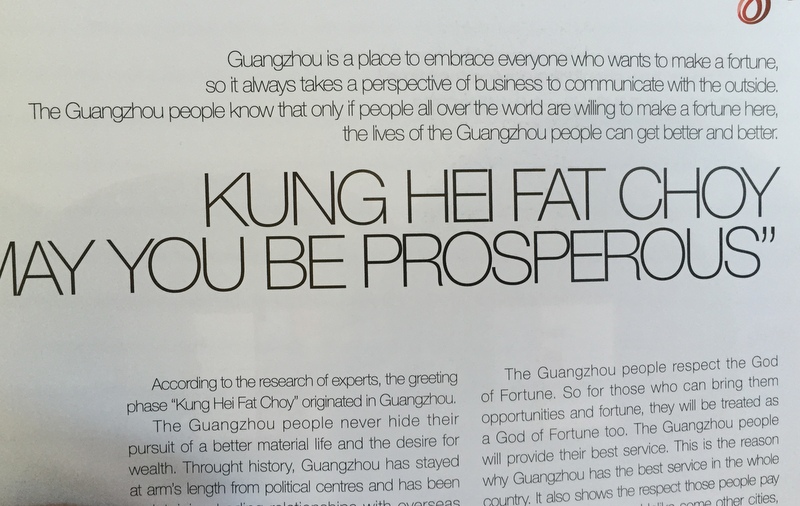

2) The in flight magazine had the article below, informing flyers that “Guangzhou is a place to embrace everyone who wants to make a fortune.”

3) The movie playing during the flight was “Fen shou da shi” (The Breakup Guru), a comedy that included a prosperity guru preaching to a stadium full of upward strivers. In the scene below he says: “our biggest dreams are the precondition that drives us to surpass….” something or other. It was a secular Chinese version of the prosperity gospel preachers we have in the USA. (Granted, the movie was making fun of this guy, but his type is recognizable to Chinese movie-goers).

4) At one point during the flight I checked my watch and saw that my seat-mate, an 18 year old Chinese college student, was looking at my watch. I assumed he wanted to know the time so I turned the watch toward him. He said “Omega. I recognize that mark.” I’ve worn this watch for 18 years and nobody has ever commented on it in America or Europe.

These are all small things, but it was notable that as I was reading Osnos on the plane, all I had to do was raise my head and look around to find four pieces of evidence that (a part of) Chinese society is consumed by the material ambition Osnos describes.

The next surprise was the air pollution. We’ve all heard so much about the awful air quality in Chinese cities, but I was still stunned by my first encounter upon landing in Guangzhou, an industrial city near Hong Kong. It was a sunny day, and when I looked straight up I could see a blue sky, photographed here through an airport window:

Yet when you look horizontally, through the haze, it looks like a foggy day, or a day with light snow:

The smog is so bad that you can actually see it in the cavernous spaces of the airport. Signs far away look a bit blurry. It looks and smells like you are walking around in a heavily trafficked underground parking garage.

The air quality in Shanghai feels slightly better, but is still far worse than anything I’ve seen in my life. But I will say this about the smog: it makes night scenes more dramatic:

Despite the pollution, the city is beautiful and fascinating. It feels very safe, the food is delicious, and I am looking forward to my three weeks here, based at NYU’s brand new campus.

Read More